- accueil >

- Numéros de la revue >

- Musique et design sonore dans les productions audi... >

- Terreurs du surnaturel contemporain : à l’écoute d... >

Conspiracy of Terror:

Music, Sound Design, and the Female Scream in Horror Trailers

James DeavilleDOI : https://dx.doi.org/10.56698/filigrane.1360

Résumés

Résumé

Cet article examine d'abord les variétés de pratiques d'intégration son-musique dans les bandes-annonces de films d’horreur, en tant que travail de design sonore et de position de la musique. J'analyserai dans un premier temps comment fonctionne l'équilibre sonore dans des exemples d'intégration de la musique et du son (Doctor Sleep, 2019), dans l'approche partagée de la partition musicale suivie du sound design (You're Next, 2013) et dans des bandes sonores composées exclusivement ou principalement de sons manipulés électroniquement (Affamés, 2021). L'article explore ensuite les implications (genrées) du cri féminin dans les bandes-annonces de films d’horreur, car contrairement à Redfern qui le limite au dialogue (2020), je considère le cri non-lexical comme se situant entre les éléments sonores cinématographiques du dialogue, la musique et les effets sonores, une sorte de « trou noir » sonore (Chion, 1999, 76). La discussion s'appuie sur la notion d'abjection de Kristeva (1982) pour étudier comment, dans les bandes-annonces de films d'horreur, le cri est rendu particulièrement puissant pour rendre abject le sujet féminin, et cela grâce au travail de design sonore afin de commercialiser les films. Comme exemples de cette pratique, j’étudie les bandes-annonces de Hostel et de The Pact ainsi que des séquences des deux bandes-annonces de Insidious : La Dernière Clé – analysées plus en détail grâce à des spectrogrammes comparatifs.

Abstract

This article first examines the varieties of sound-music integration practices in the horror trailer, as the work of sound design and music placement. It initially analyzes how the sonic balance functions in examples of the integration of music and sound (Dr. Sleep, 2019), the approach of music score followed by sound design (You’re Next, 2013), and the soundtrack consisting exclusively or predominantly of electronically manipulated sound (Antlers, 2019). I then explore the (gendered) implications of the female scream in horror trailers, as a nonlexical vocalization falling between the audio elements of dialogue, music, and sound effect, a type of sonic “black hole” (Chion, 1999, 76). The discussion draws upon Kristeva’s notion of the abject (Kristeva, 1982) to investigate how sound design and music make the scream particularly potent in abjectifying the female subject. As examples of this practice, I consider trailers to Hostel and The Pact, and—in particular depth through comparative spectrograms—sequences from the two trailers to Insidious: The Last Key.

Index

Index by keyword : Film trailers, horror film, female scream, sound design, female abjection, Michel Chion.Texte intégral

Introduction

1Among cinematic genres, the horror film has enjoyed remarkable popularity since the early 20th century1, and as such has proven to be one of the most resistant to external factors such as economic recessions and health crises. Some members of the public might even argue that living through the COVID-19 pandemic simulated the experience of a horror-film scenario. Thus a 2020 scientific study of over 300 people established that horror fans were “more psychologically resilient during the COVID-19 pandemic2”—as a cinema audience they were already familiar with the well-nigh post-apocalyptic representation of empty and silent streets in news coverage from early epicenters3. To enhance the powerful effect—and hence the sense of newsworthiness—produced by such uncanny cityscapes, composers and sound designers were challenged to create an appropriate sonic accompaniment, which typically involved threatening, low-pitched drone sounds4.

2 Such cross-over between fiction and reality in the sound design of audiovisual media is not unusual for foley-based cinematic productions, but the genre of horror has elevated the work of audio engineers and sound editors to a new level5. Mood-setting, ominous, downright scary music may have featured in horror films of the past such as Jerry Goldsmith’s Academy-Award-winning score to The Omen (Richard Donner, 1976), however more recent releases have increasingly turned to the practices of sound design to embrace the continuum of sounds required by the genre6. In horror, individual sound effects such as the creaking of a door or the smashing of glass, as well as acousmêtres in general, take on a representational eventfulness in and of themselves that one does not encounter in cinematic narrative forms such as drama, adventure, or comedy7.

3 If sound design is so vital to horror cinema and television, its role becomes even more acute in trailers, where “heightened sonic density and overdetermination” are the rule8. Indeed, the cinematic trailer counts among the most compressed audiovisual contexts in which sound design and music collectively operate9. Trailer producers seamlessly blend music and sound in the attempt to immerse the audience in the screen narrative by creating the most effective soundscape possible that will appeal to the “trailer ear10”. Of course, the mix of dialogue, sound effects, and music varies between cinematic genres, so that for comedy trailers, dialogue and (cover) music predominate in the soundtrack.

4 In contrast, the horror trailer prominently brings sound effects into the audio mix, which cultivates sound design as a formal element. For certain horror trailers, traditional markers of music—e.g. pitch and acoustic instruments—may be altogether absent11, while in others the sound effects function as the most prominent audio element12. A preview in this genre may begin with a music track to signify normalcy, yet soon sound design will take over as the horrific threat becomes tangible13. And when a song recurs throughout a horror trailer soundtrack, it almost always is a well-known tune that serves the purpose of irony, whether Lou Reed’s “A Perfect Day” in You’re Next (“Official Trailer #1,” 2013), “Silent Night” in Krampus (“Official Trailer,” 2015), or Harry Nilsson’s “Best Friend” in Child’s Play (“Official Trailer,” 2019).

5Whatever their balance between music and sound design, “horror film trailers depend heavily on the use of sonically driven affective events to produce an emotional response14”. This is one of the primary findings of Nick Redfern’s recent quantitative study of sound in horror trailers, the first attempt to subject trailers to a thoroughgoing empirical approach. The brevity and closedness of trailer texts render them ideal candidates for the computational analysis to which Redfern subjects them, yet their effectiveness as persuasive micro-media also warrants attention to features that evade quantification, beyond reduction.

6A foundational concern involves the remit of sound design in its relationship with music and the human voice: if sound effects carry the “dominant emotional tone” in horror trailers, as Redfern argues, where does that leave the scream, which trailer editors typically reserve for climactic moments of affect? He relegates screams to the realm of speech/dialogue, whereas Michel Chion positions the scream as a nonlexical phenomenon, “the unthinkable inside the thought, … the indeterminate inside the spoken, … a fantasy of the auditory absolute15”. Recent empirical studies likewise recognize the uniqueness of the human scream as a means of “sounding the alarm16”, whereby it also differs from other non-linguistic human vocalizations such as groaning and laughter17.

7Granted that the scream aurally falls between the cinematic elements of dialogue, music, and sound effect, as a type of sonic “black hole18”, it nevertheless occupies a gendered position that is unambiguously coded as female19. This gendering of the scream exposes the roots of the misogyny undergirding the horror genre, even as Chion labels the shout as belonging to the male in cinema20. The present essay will draw upon Julia Kristeva’s notion of the abject to investigate how in horror trailers the scream is made particularly potent in abjectifying the female subject in order to market movies21.

8The following discussion of the female scream in horror trailers adopts Chion’s terminology, even though its analysis departs from his emphasis on the singular occurrence of the scream (e.g. Doris Day in Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much). We first consider how some horror trailers balance sound design and music to varying degrees, as observed in the use of an ironic/anempathetic cover song (“A Perfect Day” for You’re Next), a recognizable theme in dialogue with sound effects (“Dies Irae” for Dr. Sleep), and a thoroughly integrated soundtrack of sound effects with musical qualities (Antlers). We then will explore how film studios and trailer houses exploit the intersections of gendered identity and market-driven practices in fashioning audiovisual appeals to the audience for horror. Particular attention will be paid to the female scream and how horror trailers render it especially potent by abjectifying the female subject, and that through the work of integrating sound design and music in the phenomenon of the scream, heard in examples of trailers to Hostel and The Pact. The essay closes with a comparative study of the domestic and international trailers for Insidious: The Last Key, drawing upon the empirical evidence from spectrograms to interpret the trailer houses’ divergent deployment of female screams in marketing horror to domestic and international audiences.

1. Music and Sound Design in Horror Trailers

9In considering the marketing rhetoric of trailers, Geoffrey Ammer, president for worldwide marketing at Columbia TriStar, remarked that “the trailer is the most important element of movie advertising22”. These potent “mini-epics” promote the upcoming release of a new film through a variety of audiovisual advertising techniques, mobilized to persuade audiences to consume the advertised film in theatres. Generally, trailers convey a sense of the narrative that unfolds in the feature film, though often not in a coherent manner, so as to invite curiosity on the part of the audience. The trailer derives much of its appeal by exploiting elements like star power, genre, narrative, visual special effects, and soundtrack (the defining feature for horror).

10The horror trailer derives much of its impact from a reliance on sound design that typically integrates music into the sound mix23, although the soundtrack may separate music and sound elements or even dispense with music altogether. Music and sound conspire in the horror genre in general through the aural expression of terror and the creation of tension and expectation, relying upon such familiar audio devices as low, indistinct sounds, unexpected and irregularly paced sound events, and fraught silences. At the beginning of a horror trailer, music can serve an orienting function that establishes the believability of the narrative world; this is even more the case when the track is a well-known cover song used ironically24, such as Lou Reed’s “Perfect Day” for You’re Next (Adam Wingard, 2013) or Destiny Child’s “Say My Name” for Candyman (Nia DaCosta, 2021). In the case of trailers for You’re Next, Get Out (Jordan Peele, 2017), and The Woman in the Window (Joe Wright, 2021), for example, the preview begins with music that lyrically sets a scene using acoustic (or acoustic-like) sounds and then shifts—customarily suddenly and unexpectedly—to synthesized sound design for the rest of the trailer. The practice of introducing the trailer with a gentle musical opening helps to establish a narrative world order with which to contrast the disturbing events that upset the balance, for both the initial music and subsequent sound effects contribute to the trailer’s (in-)congruent storytelling that the horror audience expects.

11In the trailer to You’re Next, for example, the soundtrack thwarts audience expectations and disrupts the initial scenario of a holiday family gathering by traversing the liminal space between the “normal” acoustic music (“Perfect Day”) and the terrorizing sound effect at the sight of the animal (00:37). The irony established between the opening song and the subsequent horrific events persists even after the “rug pull,” for—contrary to traditional practice—Reed’s song returns in the trailer with its refrain as a paradoxical accompaniment to the visual montage and sound design of horror. The music may give pace to the succession of sights and sounds throughout, yet it remains anempathetic to the characters’ increasingly frantic emotional intensity and thus it serves to underscore the ironizing effect of the song “Perfect Day”.

12More closely considering the song’s return (starting at 01:29), the sounds accompanying the foregrounded recurrence of “Perfect Day” represent a counterpoint to the Reed cover, which initially dominates the soundtrack and in its triple time sets an almost lilting pace for the images. The sound design under the song’s re-emergence begins with synthesized effects and then—as the track recedes into the audio mix—is humanized through digitally manipulated female screams and a male shout that frenetically occur in quick succession, followed by an audio dissolve and strobe-like montage (01:58)25. The abrupt silence and stasis after the audible and visual crescendo of horror function as they should at the end of a horror trailer, yet rather than finding completion in a final, horrific sound effect, the trailer closes with the song’s final phrase, abruptly cut-off.

13The clear demarcation of cover song and sound design that both diachronically and synchronically characterizes the trailer to You’re Next remains an exception within the sonic realm of horror previews. More typical is a blending of sound effects and music to the extent that they may become indistinguishable in a trailer’s soundtrack, as illustrated by the end of the trailer to Insidious (James Wan, 2011). Editors will often introduce music or musical elements into the traditional mix of horror sound effects to provide grounding through familiarity and stability on the one hand—the single sustained piano (or synthesizer) tone at the beginning of a trailer has become a cliché—and to intensify affect and emotion on the other. Much more than in other trailer genres, the aural domain of horror trailers exists in the space between diegetic and nondiegetic registers. In other words, the audience is left uncertain regarding the provenance of the sounds they are perceiving—are they originating offscreen or onscreen? This gap—not unrelated to Robynn Stilwell’s “fantastical gap” between diegetic and nondiegetic music26—affords more freedom to sound designers to create refined and functionally hybrid sounds, whose very unfamiliarity causes such aural miscegenations to disorient and disturb their auditors.

14The Final Trailer to Dr. Sleep (Mike Flanagan, 2019) illustrates how the interweaving of sound effects and music can invoke the nostalgic memory of a film—here The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980)—, sounded through fragments of a tune—the “Dies Irae”—while viscerally terrorizing through digitally-created sound. In contrast with You’re Next, this trailer begins in the realm of sound and subsequently transitions to a pre-eminence of music with the full reveal of the telltale “Dies Irae” that figured so prominently in The Shining. Already at 00:09 we perceive in the background the first three notes in a digitally processed voice that is barely audible. An assortment of threatening individual sounds and tones then help to establish psychic terror; the first four notes of the chant theme are clearly presented on the piano at 00:48. Following a series of pitched and unpitched sounds, the trailer finally delivers the full seven notes of the “Dies Irae” tune in its original (synthesized) timbre (01:22), but overdubbed with more ominous and menacing effects. Immediately repeated, the theme and its repetition return at 01:45, more obviously the product of applied sound design, and at the very end we hear it once again in a solo keyboard presentation that is devoid of added effects. The chant serves to unify and give direction to the trailer narrative, as both a hook to its distinguished predecessor and a full participant in the storytelling of Dr. Sleep. Apart from the “Dies Irae” references, musicality also permeates the sound effects through low drones, pitched hits, and other music/sound hybridities. The voices of the characters are prominent in this trailer, where they serve as foregrounded sonic markers of the human experience, encouraging the audience to invest in and identify with the characters (victims?). The trailer creates further intertextuality through the haunting voices and images of the Grady twins and other fleeting intercuts of sound footage from The Shining.

15Here the scream becomes textual (rather than aural), to the extent that the evil Rose the Hat tells the girl Abra at 02:07 “you will scream for years,” after which we see silent screams—male and female—that are soundtracked with a rising and intensifying scream-like effect. After the twins intone their turn phrase or line “Come and play with us…”27, the audience hears a heavily processed scream, but in connection with Danny, whose mouth is paradoxically held closed by unidentified hands. The aforementioned keyboard statement of the “Dies irae” closes the trailer, as if to remind the audience of the film’s pedigree (and with a slight added horror “swoosh” at the end).

16Finally, the sonic balance may tip in the direction of sound design, where music in the traditional sense may not be introduced in the trailer at all, instead allowing sound effects to dominate the soundtrack. As Barbara McBane argues, “horror relies heavily on sound for its effects28” (McBane 2007, 268), which in practice means that sound effects may supplant music or appropriate its characteristics and functions. In the absence of a known tune or recognizable music, the audience could become more disoriented and disturbed without the grounding afforded by the familiarity of music. However, even when music in the usual sense is absent, the sound effects may take on musical qualities, especially through rhythm. Thus the trailer to Insidious (2011) begins with a ticking metronome, the pulse transforming into the sound of a rocking horse that morphs into a heartbeat, all with the same basic beat. Whether drawing upon foregrounded ambient sounds like door creaks, electronically engineered sounds, or even silences, these trailers foreground over-determined sound in order to maximize the horrific impact of their aurality.

17Such is the case with the sound design behind the trailer for a film like Antlers (Scott Cooper, 2021), where the soundtrack consists of digitally manipulated sound. This trailer, called “Myth,” was created by trailer house Buddha Jones and was nominated for a Golden Trailer Award. The audio mix here imbues the digitally generated sounds with the musical characteristics of timbre, pitch, and rhythm, whether the low-pitched drone at the beginning that introduces a threat to the wilderness lake shot or the ever quickening pace of the rhythmic hits at the end that leads to the silence before the turn phrase. Here we again encounter a climactic scream, but it is silent and in the mouth of a boy, the electronic screeching of the soundtrack serving as a surrogate voice for him.

18To the extent that all of these non-lexical vocalizations occur at a climax suggests that the scream occupies a special place within the horror trailer. It may also occur in other trailer genres like suspense, yet the female scream—alongside the wide palette of electronically generated sound effects—has become closely associated with horror previews, as a human vocality that resides outside of language and communicates on the level of the Lacanian Real. Such privileging of a certain sound is telling not only of the psychological roots of the genre, but also of the gendered implications behind its marketing strategies to a specific segment of the cinematic audience.

2. The (Female) Scream in Horror Trailers

19Foregrounded sonic markers of the human experience may occupy a significant portion of the trailer soundtrack, encouraging the audience to invest in and identify with the characters. Objective-internal sounds, where the soundtrack focuses on the physiological audition of a character through a heartbeat or breathing, for example, are often employed in the horror trailer to further this end. Such vocalities including screaming, shouting, speaking, and singing convey the narrative not merely through language but also timbrally and contextually.

20According to Chion, “the scream embodies the fantasy of the auditory absolute, it is seen [sic] to saturate the soundtrack and deafen the listener29”. Although the scream is a cry of a human order, it is cinematically reserved for female vocalities. Chion describes the “screaming point” in narrative film as “something that generally gushes forth from the mouth of a woman... a phenomenon endemic to a cinema of sadists”. Thus we would have to agree with Naomi Blacklock, who observes that “the female scream is associated with… representations of hysteria30”, which Claire King contrasts with “male composure” in the horror film Alice, Sweet Alice (Alfred Sole, 1976)31.

21Above all, the female scream in male-directed (and -consumed) films denotes a certain mastery, as exposed in films ranging from King Kong (Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack, 1933) to Berberian Sound Studio (Peter Strickland, 2013). The limitlessness of the female scream can be regarded as standing in opposition to the male shout which—according to Chion—defines a territory, a will, and power. Chion further describes the scream as embodying an absolute “outside of language, time, the conscious subject”—he refers to the scream as a sonic “blackhole”. Yet he also materializes the male experience of the female scream, which poses “the question of the ‘black hole’ of the female orgasm which cannot be spoken nor thought32”, but results in what Kyle Christensen has called the “orgasmic scream33”.

22A robust literature exists regarding female portrayals and subjectivity in horror film, although its authors consider the corpus from the prevailing visualcentric perspective of feminist film analysis—the soundtrack and its screams are of secondary importance to them. In classic feminist readings of women’s roles in the genre, Carol Clover and Linda Williams both critique the abjectification of women in the horror film, Clover considering victim roles in slasher films while Williams argues for the female victim’s gaze as resistance34. In contrast, Barbara Creed’s pioneering 1993 text The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis argues for the agency of the female monster, but it occurs according to selected types of monstrous femininity—the vampire, the witch, the possessed monster, among others—in major cinematic releases35. Reading these essays in light of a century of horror releases, the researcher must recognize that the bulk of horror films ultimately casts women in the role of victim, whether helpless or empowered.

23 Generally considered, the cry or scream of women can be interpreted as emblematizing a state of abjection, to the extent that—according to Julia Kristeva—female-abject represents that which “disturbs identity, system, order36”. These qualities we find in the female scream of cinematic horror, where female abjection (dis-)embodies itself in her “limitless” cry37. Accepting then the statement of Howard Slater that—in the horror films of John Carpenter—“the camera is the ‘male gaze’ objectively framing female abjection38”, the horror genre should serve as a natural site for the exploitation of the screams of threatened women. As Lawrence Kramer opines in After the Lovedeath, “violence against women does not so much deliver men from feminine abjection as deliver it to them; in the woman’s violated body, in her tears, pleas, screams, useless resistance, the violator finds the image of an abjection to which his masculinity is superior39”. Within this promotional economy of audible female degradation, the horror trailer will make every effort to foreground the promise of terrorizing thrills afforded by the genre.

24In cinematic narratives the placement and frequency of the scream can be more important than the quality of the sound itself—quite in contrast to real life—, and thus the scream often occurs at the convergence of plot lines for maximum impact. However, it serves a different function in the world of the trailer, whose format does not provide adequate narrative space to develop a coherent plot, let alone intersecting plot lines that would allow for a cinematic use of Chion’s screaming point. Instead, previews exploit the scream as a sonic signifier of the horror genre for promotional purposes. If the cinematic scream is immaterial, as Chion suggests, the trailer scream serves a materializing function: rather than causing us to experience the limitless, the indefinite, the trailer scream invites the audio-viewer to a visceral future cinematic experience. It is not a cry for help, but a plea to bear witness, not unlike the appeal of other promotional media but in such cases of female abjection directed at the “male ear,” extending the notion of the gaze into the sonic realm.

25 Rarely does the audience encounter a female scream in a contemporary horror trailer that is not digitally altered, however. As King observes for the soundtrack of Alice, Sweet Alice, “the particular balance of this film’s sound mix privileges and magnifies the sounds of female screams to a remarkable degree40”. The sound designer will at least add reverb to the trailer scream, although within the economy of the “trailer ear41”, this interstitial vocalization has become more of a site for sonic over-determination and excess. That the trailer’s sound designer traditionally reserves the female scream for the climactic moment just before the sudden silence and turn line confirms Chion’s assessment of its paradoxical narrative function as a deafening black hole, while at the same time it serves promotional ends as an exploitive non-lexical sonification of terror and woman’s abjection.

26 Still, close analysis of horror trailers reveal how they can confound Chion’s concept of the singular cinematic “screaming point”—a woman’s scream “at the crossroads of converging plot lines42”—by multiplying screams so that they could be considered to fulfil the functions of non-linguistic “musicalized sound effects43”. Such multiple screams serve as components of the trailer’s rhythmic schema within its overall sound design, typically increasing in frequency (and intensity) during the culminating montage of image and sound where such auralities realize a promotional aesthetic rather than accomplishing a narrative function. And the marketing relies upon abjectifying women through their terrorized and traumatized voices.

27To support these arguments, it is important to consider examples of horror trailers in greater detail. That the cases are drawn from the corpus of trailers where music and sound effects have been more or less integrated reflects the typical practice of sound design within the horror trailer44. Whether the trailer leads to the singular climactic female scream that fulfils Chion’s concept of the screaming point or its soundtrack features multiple screams that become Kulezic-Wilson’s musicalized sound effects, they all resonate beyond language and abjectify the woman both behind and within the sound.

2.1. Hostel

28The first example presents one screaming point, that of an acousmatized female voice. The 2005 trailer for Hostel (Eli Roth) opens with an ominous low figure of descending half steps accompanied by irregular percussion mixed underneath. Industrial, scraping, and metal sounds are scattered throughout the soundtrack, matched with images and cuts. There is no dialogue, but the audience does hear the shouts of one or more male victims. The music quickens in pace and begins a tonal climb that builds in intensity and peaks with a single female off-screen scream at the halfway mark, which trails off into the black screen and silence of Chion’s “black hole”.

29Until that point in the trailer there has been no suggestion of a female presence, but immediately preceding the scream we observe an image of a woman’s toe, about to be mutilated. Effectively, the unidentifiable female has been dissected by the camera, a common practice in music videos that visually represent parts of women’s bodies45. In their study of media ads that exploit women, Kaitlynn Mendes and Cynthia Carter noted how the images “often portrayed fragmented body parts rather than the whole person, which had the effect of de-humanizing the subject46”. In conjunction with the scream, the image of the disembodied foot serves to materialize the aural abjection in the promotional rhetoric of the horror trailer. The trailer studio selected and edited the shot and sound for the economy of the cinematic market place, not to build suspense or advance plot but rather to foreground what the film will offer audiences. However, rather than sounding at the final climax, we hear it at the trailer’s midpoint, followed by a black screen and silence (again, Chion’s “black hole”).

2.2. The Pact

30If one female scream can inform the audience of coming terror and abjection, how might a multiplicity of them impact trailer consumers? The trailer for the 2012 film The Pact (Nicholas McCarthy) reveals little of the plot, yet both the visual narrative and soundtrack inform the potential audience that in looking for a missing sister, the female protagonist and her psychic associate search a sinister house. There they encounter malevolent supernatural forces that exert considerable malicious physical power over the women, which occasions their diverse screams at 00:42, 01:16, 01:34, 01:37, and 01:42, the last the most extended and climactic of the lot.

31The initial scream of surprise sets off a sonic frenzy around the midway point in the trailer, which transports the audience from a mode of situational orientation (someone has disappeared within a house and her friends are looking for her) to one of visceral experience (we are visually and aurally immersed into the terrifying threats in the house). This first scream is a key point in the promotional rhetoric, since immediately afterwards we see a series of press comments, spaced out through the rest of the trailer. Sound design now takes charge, with a low-pitched grinding half-step, sudden synch-point hits, and electronically modified whispers. We experience another full, intense female scream at 01:16—this time digitally manipulated—, which unleashes a quick montage of action shots that lead to the caption “scream out loud scary”. At that point the montage suddenly ceases while the women’s frantic voices fade, and the camera and microphone enter into a dark hole in the wall (01:24): this accords with Chion’s description of the black hole, as a place and moment “where speech is suddenly extinct… the exit of being47”. Represented by a black screen and the sound of panicked breathing, the hole opens onto a very quick series of horrifying images, frightening sound effects, and densely packed female screams at 01:34, 01:37, and 01:42. These climactic seconds become a sonic crescendo of horror, culminating in one final mega-scream, all of which “momentarily mutes all other sound”48 and over-saturates the ear, even as it structures the trailer’s headlong rush to its dire close. These women cry out in terror, but also scream their abjection into the ears of the consumers for horror films.

2.3. Insidious: The Last Key

32The Insidious horror franchise has acquired a considerable following, resulting in five films—three chapters (James Wan, 2011, 2013 ; Leigh Whannell, 2015), Insidious: The Last Key (Adam Robitel, 2018), and Insidious: The Dark Realm (Patrick Wilson, 2021)—that all involve spirits tormenting the Lambert family from a domain called “The Further”. The first two were filmed under the direction of James Wan, noted director of Saw (2003, 2004) and The Conjuring (2013, 2016), and feature veteran actor Lin Shaye—a “scream queen”—as the main protagonist, psychic/medium/demonologist Elise Rainier. As an (increasingly) elderly woman (born in 1943), Shaye makes for an interesting choice as a central heroic figure, whose character is revealed in the trailers as taking charge over the horrifying situations (she provides the explanatory voiceovers) and yet herself screams, as do the “final girls49”.

33It is interesting to compare the two available trailers for Insidious: The Last Key entitled “Scream” and “Family”; the latter—created by established trailer house Buddha Jones—was nominated for a Golden Trailer Award in 2018. IMDb indicates that “Family” served as the trailer for international release, “Scream” for domestic use, the most evident differences between them consisting in the order of the storytelling. The narratives of both trailers share certain features: they introduce Elise as an experienced paranormal specialist, reveal that the haunted house to which she has been called once belonged to her family, and present the horrifying supernatural entities and occurrences encountered by Elise and her companions. The trailers do not identify the individual characters, who—other than Elise and her helpers—are new to the franchise, and the audience does not discover anything more of the plot than that it revolves around a demon from her past. This lack of narrative detail confers greater prominence to the trailers’ scenes of horror and torture, which through their heightened visual density and sonic over-determination acquire a viscerality for moviegoers that the film itself may not deliver50.

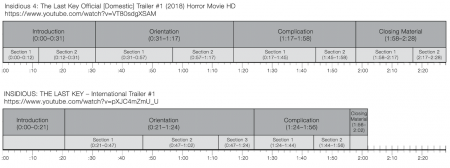

34Nevertheless, “Scream” and “Family” tell diverging stories based on the ordering and relative length of visual and sound material, as reflected in the comparative structural charts of Figure 1.

Figure 1: Insidious Trailer Form Diagrams

35The international trailer plays it safer by following the time-tested pattern of saving the climactic “scream fest” for the final ten seconds (beginning at 01:46), just before the closing title card. To the extent that we have already heard a brief strangled scream at 01:11 and a pair of short, enhanced female screams at 01:23 and 01:26, the narrative here follows the structural trope for horror trailers (and for trailers in general) of building toward a peak sonic experience at the close. Given the scene’s position in the trailer, we may well presume that the terrorized character is “final girl” Melissa, whose life is put into jeopardy by the attack.

36In comparison, the appropriately named domestic trailer “Scream” “inverts the structure of trailers for contemporary Hollywood horror films by presenting its most emotionally intense scenes first51”, as Redfern discovered for the trailer to The Last House on the Left (Dennis Iliadis, 2009). Positioning the attack—the trailer’s most horrific scene—near the opening has the effect of decentering the narrative arc, thereby introducing curiosity concerning the identities and fates of these characters. Thus the inverted placement of the attack scene functions more like a preliminary enticement into the subsequent terrifying story that follows than a climax of tension and horrors. The trailer editor has ensured that the audience perceives those first forty seconds as introductory by inserting the Universal logo immediately afterward, followed by the orienting information for the trailer narrative.

37While the audience-voyeurs of the attack scene may regard it as a scene of un-speakable (yet eminently screamable) horror, its female protagonist terrorized by a powerful, malevolent creature, another, more abjectifying layer of meaning emerges when we consider what the monstrously male KeyFace enacts. By inserting the key into Melissa’s flesh, specifically the cavity of her throat, he is committing the most severe sexual violence of rape, as Kristeva’s “shameless rapist52”. The key’s double meaning is enhanced by a sound of fleshy viscosity as he turns it, followed by a click that signifies completion (00:34 and 01:55). One need not have digested and understood the theories of Freud to perceive the sexual meanings behind the forced entry of a part of a male’s anatomy into a woman, which the protagonist here attempts to resist with the weapon of a shattering vocality that becomes Chion’s “black hole”, that ”exit of being” into which her screaming sonically lapses. Rather than closing the trailer with the customary “scream fest” and an unknown outcome for the young woman—though every aficionado of the genre knows the “final girl” will survive the “final scream”—the trailer editor lets her audibly flatline over the moving image of her vocalized terror, which astute audience-voyeurs might intuit as signifying the powerlessness of an altered state (here a coma).

38Melissa is also silenced on her last scream in the closing climactic sequence of the international trailer “Family,” her voice completely cut off in favor of KeyFace’s “shushing”. This gratuitous gesture of stifling also intensifies her abjectification, in the sense of Kristeva’s “terror that dissembles, …hatred that smiles53”. His monstrous hushing is all too reminiscent of the gloating rapist engaging in the ironically subdued vocality of total mastery, yet it also obliquely suggests the possibility of Melissa’s continued survival and serves the trailer structure as the (horrific) turn phrase after the post-climactic silence.

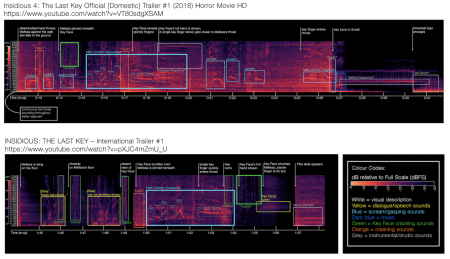

39Sound design is front and center in making all of this happen for the seemingly parallel attack/rape scenes in the domestic and international trailers for Insidious: The Last Key. It is important to observe how the scenes draw upon much of the same visual and audio material from the film, yet evoke different responses within the audience-voyeurs, also when considered independently of their immediate trailer contexts. Making the underlying structures evident at a deeper level, the spectrograms for these scenes (Figure 2) vividly visualize the disparities, unveiling how each attempts to appeal to genre fans and franchise followers.

Figure 2: Insidious Trailer Spectrogram Comparison

40If the elements of sound design were to be assessed in their overall effect in each trailer54, the analyst could posit that the nineteen-second domestic-trailer attack/rape scene places greater emphasis on Melissa’s trauma (or human fear), while in the international trailer the briefer thirteen-second segment focuses on KeyFace (the frightful demon). The close readings of the audio enabled by the spectrograms help to establish these observations, which involve the screams themselves (characteristics, frequency, and placement), other sounds (KeyFace, the drone, the impulse/flatline frequencies), the silences, and the synchronization of the visual and sound tracks. Even a cursory examination of the two spectrograms reveals an enhanced aural continuity and intensity for the domestic (“Scream”) trailer, whereas “Family” appears to operate on a more sinister level through fragmentation and understatement.

41The screams bear detailed analysis, since they variably connote within the trailers and as such fulfil differing aesthetic and promotional functions55. The spectrograms present distinct “screaming points,” with the highlighted blue boxes representing a four-second “Main Scream Sequence” that is almost identical between the two trailers; other screams are clustered around it. Keeping in mind that such horror trailers (and films) feature constructed yet quite realistic screams56, it is possible to identify two basic scream types in the attack/rape scene, a gasp and a fully-embodied scream, the former serving as a physiological escalation and emotional intensification to the latter. The gasps of the Main Sequence are articulated by indrawn breaths that allow for the expression of Melissa’s rising terror, which registers through increasing values on the dBFS—decibel full scale—vertical axis for amplitude. It is important to note that while the “Main Scream Fragment” may not exceed the amplitude of the gasps, it achieves a powerful statement through an extended duration.

42Listeners to Melissa’s screams at 00:18 and 00:26 of the domestic trailer cannot but hear into her terrified vocalization the sounds of abjection, especially as they fade. While the gasps are typically represented by ascending contours, the screams tend to fall off in their cadence. The number and density of screams are congruent with the visual imagery of Melissa’s profound fear, which can be regarded as metonymy for human misery and trauma in the face of inhumanly monstrous actions. This short scene packs in seven discrete screams and—depending on evaluation criteria—four gasps, underscored by unidentifiable sounds that assist in climax building.

43In the international trailer, the attack/rape scene directs attention to KeyFace by privileging, almost to the point of fetishizing, the cracking sounds of his digits and by devoting comparatively more screen time to the monstrous demon than to his victim. Indeed, the five-fold iteration of those cracks — three times by themselves — provides at once a counterbalance to and motivation for the screams, in either case serving to foreground KeyFace and his evil intentions. Even the sound design behind Elise’s inserted voiceover fragments, which reference the terror of hauntings, could be regarded as distracting audience attention from Melissa. And Melissa’s final scream at 01:52-01:53 lacks the crescendo from sound design that made the initial climax in “Scream” so shattering; then again, the lower intensity in “Family” supports the contention that this trailer focuses on the “shameless rapist”.

44 One final element made evident by the spectrograms is the comparative use of silence in the attack/rape scenes. Other than his “shush,” the attacker KeyFace remains silent in face of the victim’s vocalized defense through the scream. Moreover, in keeping with the international trailer’s overall aesthetic of fragmentation, this particular scene incorporates several moments—literally microseconds—of black screen and no sound, including the functional pause between the final scream and title card. The domestic trailer on the other hand features no audible pauses in the soundtrack: sound design has insured that something is always happening in the aural realm, even under black screens. The spectrogram for “Scream” (Figure 2A) also reveals the presence of a barely audible, low-pitched tone throughout the scene, performing a role as another source of continuity.

45 The same observations regarding sound design in the attack/rape scene can be applied to the other sections of the trailers. In its fracturing of narrative elements, the international trailer inserts individual sound effects from a variety of sources, including the sounds of extended technique on traditional instruments and a callback to Bernard Herrmann’s Psycho screeches in the montage sequence. In contrast the sound design of the domestic trailer creates a more continuous soundscape, e.g. consistently deploying the low frequency tone. In both trailers, however, the attack/rape visually and aurally represents the most significant and memorable scene, rendered as such by the abjectifying screams of the protagonist-victim. However the analyst interprets that scene’s placement within the trailer narrative, there can be little doubt that Melissa’s screams also helped to sell the cinematic experience of Insidious: The Last Key to the market for horror.

Conclusions

46As a non-linguistic human vocalization, the female scream on screen fills the sonic space between spoken language, sound effect, and music, resonant with meaning though non-lexical (communication on the level of the Lacanian Real)57, a cry of distress yet also a call to the box office (promotion aimed at a specific market). Sound designers can digitally manipulate it, but the female scream must remain in some way recognizable in the trailer, as much for the economy of audiovisual promotion as for any aesthetic rationale. And unlike Chion’s singular screaming point for a cinematic narrative, multiple screams have become de rigueur for horror trailers, as over-determined sonic markers denoting and decrying female abjection on the one hand, yet also a viscerally powerful medium for hailing fans of the horror genre.

47 Redfern has well established the significance of sound design for the horror trailer and the value of empirical analysis for studying certain elements of these audiovisual texts58. The current essay has attempted to problematize one aspect of that soundscape through a study of both the uses and meanings assigned to the female scream, accomplished via interpretive readings of music, sound, and screams in select horror trailers and close comparative analysis of spectrograms for two trailers created for the same film. As observed, music can play a central role in the horror trailer narrative, especially when a cover song is deployed to ironic ends, like Lou Reed’s “A Perfect Day” in the trailer to You’re Next: there the scream is reserved for its climactic potential. More often than not, however, the female scream functions within a trailer soundscape dominated by synthesized and electronically manipulated sounds, such as the single scream in Hostel or the cluster of screams at the end of The Pact. The “Scream” and “Family” trailers for Insidious: The Last Key most clearly (and troublingly) visually and sonically illustrate the abjectification of women through the protagonist/victim Melissa’s scream in the attack/rape scene featuring the monstrous KeyFace. The analyst could argue for her defensive agency through her screams, yet the researcher must also consider the misogyny underlying the symbolic rape.

48 This project suggests a variety of directions for future research on the topic of music, sound design, and the female scream in horror trailers. Testing the hypotheses surrounding the valence of music, sound effect, and scream upon cinema audiences would undoubtedly yield valuable results. The phenomenal sound of the screams used in horror trailers could be subjected to closer empirical analysis, through more finely tuned audio analysis such as Sonic Visualizer to obtain a morphology of trailer screams59. Indeed, spectrograms could centrally figure in comparatively exploring aural practices in horror trailers, possibly identifying styles for particular trailer houses and their sound designers.

49 Finally, scholarship would benefit from investigating and exposing the misogyny behind the exploitation of the female scream in trailers. Recent scholarly literature has begun to dismantle this misogyny in horror films, regarding the scream as a potential site of resistance and possible pleasure for women60. Still, it is difficult to reclaim the horror trailer that trades in depicting intense scenes of human misery and female abjection, and through its marketing draws particular attention to the sounds of women reacting to horrific scenarios through screaming. As the genre of horror film continues to thrive, what remains is the question of whether it is appropriate to degrade and abjectify women in its trailers.

Notes

1 An extensive bibliography exists for horror film, its scholars having explored such issues as the history, aesthetics, psychology, and reception of the genre. Noteworthy texts include Noel Carroll’s pioneering The Philosophy of Horror, or Paradoxes of the Heart, London: Routledge, 1990; Adam Lowenstein’s influential essay “Living Dead: Fearful Attractions of Film,” Representations, no. 110, 2010, 105-128; Murray Leeder’s impressive historical overview Horror Film: A Critical Introduction, London: Bloomsbury, 2018; and Barry Keith Grant’s meritorious collection Robin Wood on the Horror Film: Collected Essays and Reviews, Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2018.

2 Coltan Scrivner, John A. Johnson, Jens Kjeldgaard-Christiansen, & Mathias Clasen, “Pandemic Practice: Horror Fans and Morbidly Curious Individuals are More Psychologically Resilient During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” in Personality and Individual Differences, vol. 168, January 2021, 110397, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110397.

3 James Deaville & Chantal Lemire, “Latent Cultural Bias in Soundtracks of Western News Coverage from Early COVID-19 Epicenters,” in Niels Chr. Hansen, Melanie Wald-Fuhrmann, & Jane Whitfield Davidson (eds), Social Convergence in Times of Spatial Distancing: The Role of Music During the COVID-19 Pandemic, Frontiers of Psychology, July 14, 2021, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.686738/full.

4 Ibid.

5 Katherine Quanz, “The Struggle to be Heard: Toronto's Postproduction Sound Industry, 1968 to 2005,” PhD dissertation, Wilfrid Laurier University, 2016.

6 See Philip Hayward (ed), Terror Tracks: Music. Sound and Horror Cinema, London: Equinox, 2009, and William Whittington, “Horror Sound Design,” in Harry M. Benshoff (ed), A Companion to the Horror Film, 168-185, Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell, 2014.

7 See Lisa Coulthard, “Acoustic Disgust: Sound, Affect, and Cinematic Violence,” in Liz Greene & Danijela Kulezic-Wilson (eds), The Palgrave Handbook of Sound Design and Music in Screen Media, 383-393, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016, and Whittington, op. cit.

8 James Deaville & Agnes Malkinson, “A Laugh a Second? Music and Sound in Comedy Trailers,” in Music, Sound and the Moving Image, vol. 8, no. 2, 2014, 125. Regarding trailers in general, a small but important body of literature has arisen, virtually all of it since 2000. The following titles represent monographs by the leading scholars in the field of trailer studies: Vinzenz Hediger, Verführung zum Film: Der amerikanische Kinotrailer seit 1912, Marburg, DE: Schüren Verlag, 2001; Lisa Kernan, Coming Attractions: Reading American Movie Trailers. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2004; and Keith M. Johnston, Coming Soon: Film Trailers and the Selling of Hollywood Technology, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009.

9 James Deaville, “The Trailer Ear: Constructions of Loudness in Cinematic Previews,” in Carlo Cenciarelli (ed), The Oxford Handbook of Cinematic Listening, 450-465, New York: Oxford University Press, 2021.

10 The trailer ear “is a discursively constituted, experience-based physiological response to trailers as audiovisual texts that exploit sound’s materiality while engaging the listener’s subjectivity,” Ibid., 450.

11 See for example “Official Trailer #1,” The Pact (2012), “Official Trailer,” Hereditary (2018), and “Final Trailer,” Insidious: The Dark Realm (2021).

12 “Official Main Trailer,” The Conjuring (2013), “Official Trailer,” Don’t Breathe (2016), “Official Trailer 1,” Get Out (2017), and “Official Trailer,” Brightburn (2019).

13 “Official Teaser Trailer,” It (2017), “Official Trailer,” Down a Dark Hall (2018), and “Official Trailer,” Old (2021).

14 Nick Redfern, “Sound in Horror Film Trailers,” in Music, Sound and the Moving Image, vol. 14, no. 1, 2020, 66.

15 Michel Chion, The Voice in Cinema, Claudia Gorbman (trans), New York: Columbia University Press, 1999, 77.

16 Pascal Belin & Robert J. Zatorre, “Neurobiology: Sounding the Alarm,” in Current Biology, vol. 25, September 21, 2015, R805–R806.

17 Jay W. Schwartz, Jonathan W.M. Engelberg, & Harold Gouzoules, “Was That a Scream? Listener Agreement and Major Distinguishing Acoustic Features,” in Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, vol. 44, 2020, 233–252, at https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-019-00325-y.

18 Chion, 76.

19 Disha Handa & Renu Vig, “Distress Screaming vs Joyful Screaming: An Experimental Analysis on Both the High Pitch Acoustic Signals to Trace Differences and Similarities,” in 2020 Indo – Taiwan 2nd International Conference on Computing, Analytics and Networks (Indo-Taiwan ICAN), 190-193, 2020, at Doi: 10.1109/Indo-TaiwanICAN48429.2020.9181340.

20 Chion, 78.

21 Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, Leon S. Roudiez (trans.), New York: Columbia University Press, 1982.

22 Carol Ames, “Summer Movies: Box-Office Battles, Begun Long Ago and Far Away,” in The New York Times, May 8, 2005, A2.

23 Redfern, 2020.

24 Here “irony” signifies the tension and play at work in the union of a song that carries one set of meanings with a visual narrative that contradicts those meanings, in our example idyllic or romantic ballads with scenes of horror. The “uncanny" plays a role here, for as Jonathan L. Crane posits, “allied with the uncanny, irony’s orientation [in horror] is… to bring the audience back to the traumas of the psyche”. Crane, “‘It was a dark and stormy night ...’: Horror Films and the Problem of Irony,” in Steven Jay Schneider (ed), Horror Film and Psychoanalysis: Freud’s Worst Nightmare, 154, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

25 The human vocalities loosely synch with images of characters to give them a “diegetic-ness,” and that in counterpoint to the obviously non-diegetic Reed cover.

26 Robynn J. Stilwell, “The Fantastical Gap between Diegetic and Nondiegetic,” in Daniel Goldmark, Lawrence Kramer & Richard Leppert (eds), Beyond the Soundtrack: Representing Music in Cinema, 184-202, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007.

27 The turn phrase or line (also known as the “button”) is the succinct statement that occurs in the great majority of trailers between the sudden post-climax silence and the closing gestures (with release information). It typically consists of a short dramatic phrase like Gandalf’s “How shall this day end?” in the Official Main Trailer to The Hobbit: The Battle of Five Armies (2014) or Anthony Hopkins’ “There’s something funny going on” in the Official Trailer to The Father (2020).

28 Barbara McBane, “Asynchronicities: Sound-Image Disjunctions, Deviant Meanings, and Euro-American Cinema,” PhD dissertation, University of California Santa Cruz, 2007.

29 Chion, 77.

30 Naomi Blacklock, “Conjuring Alterity: Refiguring the Witch and the Female Scream in Contemporary Art,” PhD dissertation, Queensland University of Technology, 2019, 5.

31 Claire Sisco King, “Acting Out and Sounding Off: Sacrifice and Performativity in Alice, Sweet Alice,” in Text and Performance Quarterly, vol. 27, no. 2, 2007, 138.

32 Chion, 77.

33 Kyle Christensen, “A Dynasty of Screams: Jamie Lee Curtis and the Reinterpretation of the Maternal Voice in Scream Queens,” in Critical Studies in Media Communication, vol. 36, no. 3, 2019, 275.

34 Carol J. Clover, “Her Body, Himself: Gender in the Slasher Film,” in Representations, no. 20, Special Issue: Misogyny, Misandry, and Misanthropy, 1987, 187-228, and Linda Williams, “When the Woman Looks,” in Barry Keith Grant (ed), The Dread of Difference: Gender and the Horror Film, 15-34, Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996.

35 Barbara Creed, The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis, London: Routledge, 1993.

36 Kristeva, 4.

37 Chion, 78.

38 Howard Slater, “Autotraumatisation: On the Movies of John Carpenter,” in Datacide: Magazine for Noise and Politics, vol. 5, January 1999, at https://datacide-magazine.com/autotraumatisation-on-the-movies-of-john-carpenter/. The “male gaze” is a foundational concept in film theory, designating the act of depicting and of viewing women on screen as sexual objects. The concept was most famously applied to film by Laura Mulvey in her groundbreaking essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in Screen, vol. 16, no. 3, 1975, 6-18.

39 Lawrence Kramer, After the Lovedeath: Sexual Violence and the Making of Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000, 121.

40 King, 134.

41 Deaville, 2021.

42 Chion, 77.

43 Danijela Kulezic-Wilson, Sound Design is the New Score: Theory, Aesthetics, and Erotics of the Integrated Soundtrack, New York: Oxford University Press, 2020, 50.

44 Redfern, 2020.

45 It is interesting to compare different approaches to this fragmentation of women’s bodies in music videos, as their practices have changed over time. See for example Sheri Kathleen Cole, “‘I am the eye. You are my victim,’ The Use of Pornographic Ideology in the Music Videos of Duran Duran,” in Enculturation, vol. 2, no. 2, 1999, at http://enculturation.net/2_2/cole/ ; Carol Vernallis, “Strange People, Weird Objects: The Nature of Narrativity, Character, and Editing in Music Videos,” in Roger Beebe & Jason Middleton (eds), Medium Cool: Music Videos from Soundies to Cellphones, 111-151, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007 ; and Claudia Kozman, Amr Selim & Sally Farhat, “Sexual Objectification and Gender Display in Arabic Music Videos,” in Sexuality & Culture, vol. 25, 2021, 1742–1760.

46 Kaitlynn Mendes & Cynthia Carter, “Feminist and Gender Media Studies: A Critical Overview,” in Sociology Compass, vol. 2, no. 6, 2008, 1707.

47 Chion, 79.

48 Anne Cranny-Francis, MultiMedia: Texts and Contexts, London: SAGE, 2005, 65.

49 This term is taken from the nomenclature associated with slasher/horror films, where the central female protagonist holds out to the end against a threat, whether human or supernatural. See Janet Staiger, “The Slasher, the Final Girl and the Anti-Denouement,” in Wickham Clayton (ed), Style and Form in the Hollywood Slasher Film, 213-228, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

50 Of course the film features a narrative arc, character development, and suspense, none of which are well served through trailer concision.

51 Nick Redfern, “Computational Analysis of a Horror Film Trailer Soundtrack with Python,” n.d., at https://www.academia.edu/43289938/Computational_analysis_of_a_horror_film_trailer_soundtrack_with_Python.

52 Kristeva, 1982, 4.

53 Ibid.

54 My thanks to Chantal Lemire for these important comparative observations.

55 A considerable psychophysiological literature has arisen around questions of affect and effectiveness of a woman’s screams. See among others, Luc H. Arnal, Adeen Flinker, Andreas Kleinschmidt, Anne-Lise Giraud & David Poeppel, “Human Screams Occupy a Privileged Niche in the Communication Soundscape,” in Current Biology, vol. 25, no. 15, August 3, 2015, P2051-2056; Belin & Zatorre, 2015; Schwartz et al, 2020; and María Edurne Zuazu, “One Scream is All it Takes: Voice Activated Personal Safety, Audio Surveillance, and Gender Violence,” in Sounding Out! June 21, 2021, at https://soundstudiesblog.com/2021/06/21/one-scream/.

56 The fan base would not accept anything less than the greatest possible authenticity.

57 About the Lacanian Real in film, see especially Todd McGowan, The Real Gaze: Film Theory after Lacan, Albany, NY: State University Press of New York, 2007.

58 Redfern 2020.

59 Chris Cannam, Christian Landone & Mark Sandler, “Sonic Visualiser: An Open Source Application for Viewing, Analysing, and Annotating Music Audio Files,” in Proceedings of the ACM Multimedia 2010 International Conference, 1467–1468, New York: ACM, 2010, at https://doi.org/10.1145/1873951.1874248.

60 Relevant sources include Erin Harrington, Women, Monstrosity and Horror Film: Gynaehorror, New York: Routledge, 2019; and Tiffany Basili, “Final Girls and ‘Mother’: Representations of Women in the Horror Film from the 1970s to the Present,” MA Thesis, University of Sydney, 2021.

Citation

Auteur

Quelques mots à propos de : James Deaville