- accueil >

- Numéros de la revue >

- Musique et design sonore dans les productions audi... >

- Hybridités musico-sonores : repenser l’écoute ciné... >

Fantastic Beasts and their Sonic Nature

Intersections of Music and Sound in Harry Potter films

Jamie Lynn WebsterDOI : https://dx.doi.org/10.56698/filigrane.1242

Résumés

Résumé

Cet article explore les design sonores des cinq collaborations distinctes des huit films Harry Potter, chacune d'elles créant de nouvelles façons d'assurer la cohésion de l'histoire et la continuité de la série, et de nouvelles manières de voir, d’entendre et de se soucier du parcours de Harry. Lorsque nous examinons le rôle des animaux, en particulier, nous trouvons des sons qui sont reliés à la fois au connu et à l'inconnu, distillent des thèmes et des sous-textes et révèlent des conflits intérieurs. J'accorde une attention particulière aux cinquième et sixième films (L’Ordre du Phénix et Le Prince de sang-mêlé) dans lesquels des éléments sonores sont intégrés de façon sensuelle, nous permettant de comprendre les récits par le sentiment et la sensation physique plutôt que par des indications prescriptives. Les effets sonores musicalisés introduisent l’accompagnement musical ; celui-ci prend le relais des effets dans cette approche fortement nuancée qui permet aux spectateurs d’expérimenter – plutôt que de simplement en être témoins – comment Harry trouve son chemin à travers des sphères et des circonstances variées. De plus, cette approche a un impact crucial sur l'arc émotionnel de l'histoire, approfondissant considérablement l'expérience du spectateur des moments personnels et émotionnels les plus transformateurs vécus par Harry.

Abstract

This article explores sound designs for the five distinct collaborations across the eight Harry Potter films, each of which carved new ways of achieving story cohesion and continuity, and for seeing, hearing, and caring about Harry’s journey. Particularly when we examine the role of animals, we find sound that intermediates between the known and unknown, distilling themes and subtexts, and revealing inner conflicts. I give special attention to the fifth and sixth films (Order of the Phoenix and Half-Blood Prince) in which audio elements are sensually integrated, allowing us to understand narratives through feeling and physical sensation rather than prescriptive cueing. Musicalised sound effects introduce underscore; underscore takes over for effects in this powerfully nuanced approach that makes space for viewers to experience—rather than merely witness—how Harry navigates varied spheres and circumstances. Further, this approach makes a critical impact on the emotional arc of the story, significantly deepening viewer experience of Harry’s most transformative personal and emotional moments.

Index

Index by keyword : Sound design, Harry Potter films, Nicholas Hooper, music for animals, Fantasy film music.Texte intégral

Introduction

1Over the course of the phenomenally popular eight-film Harry Potter series, five successive filmmaking teams adapted the relationships between music, sound, and visuals in order to realise different interpretations of Harry’s epic journey. This article explores the interplay between music and sound, drawing examples from across the eight films, while giving special attention to the fifth and sixth films (Order of the Phoenix and Half-Blood Prince) in which audio elements are especially and sensually integrated1. The collaborators for the latter, director David Yates, composer Nicholas Hooper, and sound supervisor James Mather, elevated sound effects to the foreground in parallel with an atmospheric underscore to compel physical sensation and elicit emotional response. Musicalised sound effects introduce underscore; underscore takes over for effects. This modern, powerful, nuanced approach makes space for viewers to experience—rather than merely witness—how Harry navigates his way through varied spheres and circumstances. Further, this approach makes a critical impact on the emotional arc of the story, significantly deepening viewer experience of Harry’s most transformative personal and emotional moments.

2First, I examine how sound supports animals in the magical world, contributing an emotional landscape across the film series. Realistic and fantastical creatures rarely have dialogue but are often supported with sound effects and underscore to facilitate varied perspectives on the topics the creatures represent. For instance, audio-visual alignment for owls in the first film parallels Harry’s foray into a world of magic, but facilitates humour in the second and third films, subverting an already subversive landscape. In the fourth film, the integration of sound effects and stringed instruments galvanises the emotional weight of the «unforgivable curses»2 underlining the torture and killing of a spider, while underscore in the fifth film reverently elevates the funeral of another spider. Interactions between underscore, sound, birds, and animals in the sixth and final films reflect deep sorrow, the weight of cruelty and evil, and internal strength; key components in the final chapters of the journey. Further, audio-visual animal depictions help the viewer explore narrative ideas more deeply, flexing boundaries of discomfort without the deeper emotional consequences that might be felt if the same circumstances included main characters.

3The final four films expand the magical world, integrate magical and muggle (non-magical) spaces, and synthesise the realism of human experience in the fantastical realm. These nuances are emphasised in the approaches for the fifth and sixth films. Music and sound follow Harry’s environmental experiences and emotional perspectives, parallel the atmospheric soundscape, and mimic narrative sources, blurring distinctions between music, source, and effects. When underscore and sound effect integration is the norm, it amplifies the impact when score and sound are divided—as happens for Harry’s greatest exhilaration and deepest despair in these same films, arguably among the most critical, transformative moments of Harry’s hero journey.

4The publication timing of the late Danijela Kulezic-Wilson’s book on sound design and the integrated soundtrack was especially serendipitous as it addresses strategies and properties that I find in the Harry Potter series3. In addition to resources from film music theory, I use a cross-discipline approach, drawing from published resources and my own interdisciplinary background in music, folklore, dance, gender studies, and performative narratives. Further, this study is fundamentally influenced by the work of the late music theorist Steve Larson, a mentor whose explorations of music and metaphor shaped my questions, observations, and transcription choices in this research from an early stage4. Composer Nicholas Hooper’s kind responses to my queries on this topic, as well as description of his process and inspirations are included, in addition to published resources.

1. Music and Sound for Animals

5Folklore and fiction include rich traditions of using animals to tell stories about humanity, and to serve as intermediaries between the known and unknown5. While few animals speak in Harry Potter books, sound for animals in the Potter films distills their roles and reveals key insights about the magical world. In fantasy fiction, mythological creatures and realistic animals represent human attributes; we understand animals via what we project on them rather than what animals are for themselves6. I focus on realistic animals and fantastic beasts in contrast to faerie beings, yet this is not to say that the former are not also selves7.

6Animals in storytelling symbolise inner conflicts. In Harry Potter, animals reflect both respect and ridicule, humility and bravado, longing and acceptance. Treatment of animals highlights challenging topics such as unfairness, inequality, injustice, torture, and murder; in depicting natural and magical beasts, we find the monstrous capabilities of humans. Animals represent complex ideas because humans care about animals, thus even mimetic representations of animals « confront and hold us accountable in the ethical dimension to another sentient life8 ». By using animals as proxy for human experiences, filmmakers could explore topics more freely, facilitating deeper engagement with concepts in ways that help us understand humanity9.

7Across the early Potter films, sound patterns differentiate humans from animals. Humans have dialogue with underscore, allied creatures have source sounds and underscore, and adversarial animals are supported only with sound effects or a confusion of sound effects and underscore. However, in the later films, underscore and sound effects for animal encounters combine to reflect vital narrative contexts, revealing core human experiences and vulnerabilities rather than magical prowess. These foundations often include intense, fundamental emotions such as anger, fear, sadness, wonder, joy, and love. Both Order of the Phoenix and Half-blood Prince creatively alternate and integrate diegetic sounds and underscore along with silence to support scenes with especially intense emotions. Rather than creating clarity, sound elements are layered, challenging boundaries of perception as well as boundaries of characters’ emotional integrity, control, and overflow.

1.1. Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone and Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

8In Philosopher’s Stone, and Chamber of Secrets (Chris Columbus, director; John Williams, composer; and sound supervisors Eddie Joseph then Randy Thom), animals are supported by underscore, sound effects, and in rare circumstances, dialogue. While non-magical spaces generally lack underscore10, magical encounters with animals include both: 1) an element of magical sound and 2) the animal’s own call. Magic sounds were modelled after related natural sounds (e.g., water, fire, ice). The articulation of music and sounds to accompany animals helps us understand who they are and how they stack up in the magical hierarchy. While the sound formulas are ordinary, the animal audio-visuals nevertheless reveal meaningful narrative ideas not otherwise conveyed in the story.

9Animals are critical to our introduction to the magical world. An encounter with a snake at the zoo reveals Harry’s magical abilities, making the presence of magic explicit long before dialogue affirms it. Underscore rises to the foreground after Harry speaks to the snake, alerting us to magic, and sound effects follow the snake’s flicking tongue. The snake exits the scene with a hissing, « thanks », not because it can talk, but because Harry can understand snake language. Later, messenger owls deliver Harry’s invitation to attend Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, accompanied by John Williams’s now famous “Hedwig’s Theme” waltz, and sounds of owls screeching and letters dropping. This mysterious and majestic theme was used extensively to signify magic in the first two films, and was included in all subsequent Potter films, bestowing grandeur for the magical world and deep respect for owls11.

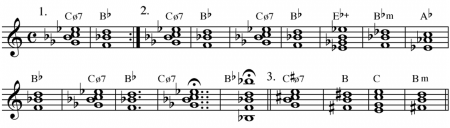

Example 1: John Williams, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone and Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, “Hedwig’s Theme”, main melody. Personal transcription using most often heard harmonies12. Melodic chromaticism, less common harmonic progressions, and tritones symbolically support mystery and magic while the melodic range, and often-heard rich orchestral timbres support grandeur13.

10Magical sounds and animal noises also combine for ridicule, facilitating permission to poke fun at both animals and people who act like animals. When cousin Dudley gobbles birthday cake intended for Harry, the thunderstorm outside is faint, yet Dudley’s ill-mannered chewing is loud. With a zap from Hagrid’s wand and a faint piggy squeal, Dudley is punished with a pig’s curly tail; “Hedwig’s Theme” re-enters, granting permission to enjoy the moment. On the Hogwarts train, Ron belittles his pet rat with an incantation with rhythmic lilt: « Sunshine daisies, butter mellow, turn this stupid fat rat yellow ». We hear a wand whoosh and the startled rat squeals, but the spell has no effect (thus, no musical response). In both cases, the sound effects disrupt the lull of dialogue much as the magical humour disrupts the illusion of normalcy. The startling magic sounds make a crescendo to a louder respective animal sound as if bringing the outcome (or lack of outcome) into being; the first example is funny because it disrupts expectation when Hagrid adds a pig tail to Dudley, while the second example is funny because it subverts expectation when Ron fails to add pigment to his rat.

11Musical underscore has the last word when humour comes from magic, but sound effects laugh last when humour results from a lack of magic. An audio-visual motif for Errol, the Weasley family’s wobbly owl, lampoons magic’s imperfections and subverts the honour established for owls via “Hedwig’s Theme”. When Errol lands clumsily, the propriety of elegant flight is disrupted in parallel with the crash sounds that disrupt the order of the music14. Each of Errol’s comedic gags begins with 1) an owl screech followed by 2) dialogue announcing Errol’s arrival, then, 3) a lilting tune accompanying Errol’s flight, until the music is interrupted by 4) sound effects for the crash landing. At first, Errol smashes into a window and immediately drops to the ground, then later, Errol crashes into the bowls of breakfast cereal in the Hogwarts Great Hall15.

12Through animals, we also see the power of sound itself defy expectations (even the expectation of magic): music has power over the fiercest contenders and even non-magical characters can succeed with sound. That is, audio-visuals with animals not only show us tangible, clear-cut magic (e.g. when a wand whoosh results in a brilliant charm), they also show us mysterious, less containable magic. Mrs. Norris (the un-magical pet cat of the Hogwarts caretaker, Filch) manifests flame torches with audible flares before meowing her alert that students have broken school rules, yet Fluffy, the fierce three-headed dog, is lulled to sleep with harp music. Likewise, the machine of sound accompanying the deadly Basilisk—a confusion of heightened sound effects for each of the serpent’s movements, highly processed monstrous roars with rumbling resonance unlike any natural world snake, and angular, dissonant underscore—transforms to a romantically pastoral, triple meter theme with reverberating naturalistic bird calls when Fawkes the phoenix arrives with his fabled phoenix song to rescue Harry (00:30 of this clip).

1.2. Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban

13The degree to which we are human or beast is determined by the integrity of what’s inside, this is the idea expressed by audio-visual alignments in Prisoner of Azkaban (Alfonso Cuarón, director; John Williams, composer; Richard Beggs, supervising sound editor). This film introduces a variety of characters with blended human/animal traits and their humanity is both clarified and obfuscated with sound. For animals, underscore imitates sounds of the body (e.g., beating heart, pounding hooves) while animal calls confirm identity. For humans (even if in animal form) underscore supports emotional cueing while sound effects reflect environment; when discernment is unclear, both sound effects and underscore foreshadow outcomes. As well, bird motifs with macabre humour mark the film at each seasonal transition, echoing humour motifs from the first films. The playfulness in the sound design for animals contributes irreverence, mystery, and also resolution, amplifying the narrative theme that not all is at it seems, and illustrating Cuarón’s vision to deconstruct Harry’s world, thus establishing a model for how the films would adapt to new leadership16.

14Source sounds are critical to encounters with the shape-shifting character Sirius Black both as a dog and as a human. Spluttering lights, wind, and squeaky, creaking playground equipment swell to the foreground before Harry first sees the black dog and hears his growl and bark. Though the dog is his transformed godfather rather than an adversary, the sound effects imply uncertain danger until this mystery is resolved, and create continuity with Harry’s eventual meeting with Sirius (the man) in the creaking Shrieking Shack. « Finally the flesh reflects the madness within », his friend Remus Lupin remarks upon seeing him, equating madness (or, a lack of rationality) with his human rather than animal form. In contrast, Lupin transforms into a werewolf unwillingly at the full moon. Blistering brass gestures cue visuals of his bloodshot eye as the volume of his heartbeat increases alongside pulsing timpani. Sirius reminds Remus of his humanity, « You know who you truly are Remus! This heart is where you truly live; this heart here! ». When the wolf whimpers, characters are unsure whether he is man or beast, but when he howls, they know that his humanity is beyond reach. Alternatively, their estranged friend Peter Pettigrew has been hiding for years as Ron Weasley’s rat Scabbers. In addition to the rat squeals heard throughout the films, Williams includes a rhythmically persistent, chromatically angular harpsichord motif occurring each time Peter is seen on the magical Marauder’s Map; foreshadowing how Peter is exposed, scampering across a decrepit keyboard in the Shrieking Shack. These examples show how sound embodies the presence or absence of shape-shifting characters for the purpose of creating mystery, navigating both their human and animal forms, and aligning with resolutions.

15Three more examples reveal human forms with animal attributes, and an animal with human dignity. The soul-sucking dementors look like hooded human skeletons, but are scored with codes for animal adversaries, screeching like birds at times, and with power to deprive one’s humanity. Their sound support relays their privation of goodness with dramatic truth: a lack of true pitch, timbre, resonance, or tonality, contributing to a frisson effect, in which the violation of musical expectation causes a chilling sensation17. For instance, when they attack Harry on the train, we hear supernaturally breathy inhalations paired with rumbling basses, tremolo strings, descending chromatic gestures played by col legno strings, slicing piccolo motifs, prepared piano and harmonic dissonance, alongside narrative sounds from squeaking train wheels, rhythmic punctuation of the jostled train, and the crackling of ice as the windows develop frost.

16In contrast, music for Buckbeak the hippogriff seems to elevate him. « First thing you wanna know about hippogriffs is that they’re proud creatures … » Hagrid says, by way of introduction, imitating a royal bugle call with a « Da da-da da! » before we hear bird noises like a bass clef chicken then we see the hippogriff, a winged horse with an eagle’s head which loudly snarfs down a dead ferret18. Despite the gauche, unaccompanied introduction, the hippogriff requires courtly manners: Harry must bow to meet approval (a stick cracks underfoot, highlighting Harry’s lack of grace). Buckbeak bows back, and as Hagrid places Harry on the beast’s back, underscore joins sound effects, with thunderous timpani pounding as hooves on the ground, then Buckbeak’s through-composed theme music usurps all other sound effects, affirming the human-quality nobility of the powerful creature through underscore.

17The Patronus charm channels intense human happiness into a powerful shield in the image of an animal. The charm tone was influenced by Cuarón’s desire to re-craft the sound of wands into wispy, flutey magic with occasional choral aura in lieu of the explosive whoosh19, and evolves throughout the film following Harry’s emotional maturity and development as a wizard. When Prof. Lupin casts a Patronus against the Dementors on the train, a flutey whoosh and consonant choral voices dispel the breathy dissonance of the dementors. When Harry casts his first Patronus in Lupin’s study, we hear a similar flutey whoosh with choral voices, plus a horn and tolling bells playing Harry’s theme for longing (a motif indicating a happy memory of his parents). When Harry casts the charm against the real dementors, we hear the whoosh, but no choral voices: the spell isn’t strong enough. Then, Harry sees the Patronus, a stag, in the distance, we hear an orb of magical sound, strong horns, and a fanfare of brass as the stag dispels the dementors. When Harry revisits the scene with the time-turner (a time-traveling device), he casts the stag Patronus himself, again with the orb of sound, and the additional horn melody alerting the viewer that he is thinking of his love for his parents and that he has matured into a new power. That is, the more Harry puts his inner world into the charm (made explicit through orchestral underscore, coded for human emotion), the more distinctive and powerful the animal image becomes.

18Macabre humour follows a happy bird and an irreverent tree to signal each seasonal transition. Each motif is a unique vignette combining to make audio-visual form within the film, while creating continuity with comedic ideas from the first films. First, bells toll as a fast-paced flute melody both imitates and accompanies a bluebird’s twitters as it flies through a warm autumn day (PoA DVD 28:47), then bursts into a puff of feathers on impact with a branch of the Whomping Willow tree. Next, “Hedwig’s Theme” supports Hedwig’s flight from dry autumn (PoA DVD 58:23) to winter as the sky produces snowflakes, and the ground turns white with snow. Then, somber music continues from a previous scene to visuals of a butterfly on a bulb flower, then to the Whomping Willow covered with melting snow (PoA DVD 1:07:03). The Willow shakes its branches, and snow splatters the camera lens (i.e., a comedic violation of the invisibility of the lens). Finally, “Hedwig’s Theme” supports the lighthearted flight of a songbird who is subsequently extinguished by the spring leaf-covered limbs of the Whomping Willow (PoA DVD 02:05:50)20.

1.3. Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire

19Music and sound for animals in Goblet of Fire (Mike Newell, director; Patrick Doyle, composer; and Sam Auguste, supervising sound editor) discern allies from adversaries, and expose devaluation of expendable creatures. Those with human traits (e.g., Veela and Mer folk) are given coherent dialogue and melodic underscore, as well as sound effects, while creatures portrayed as animals receive unintelligible calls and sound effects. Categories based on coherence align with Aristotle’s principle, albeit imperfect, that rationality distinguishes humans from animals. In critical moments, varied sound elements are integrated to maximise emotional impact, rather than separated sequentially as had been done previously. Through animal encounters, the main characters (as well as viewers) are confronted with moral and ethical discernment: how do we perceive and respond to sentient beings that are different from us? While dialogue juxtaposes good and evil (and evil imposters), the sound design shows how power, even in the so-called good magical world is often imperfect, unjust21.

20Following classic Hollywood patterns, alternation between music for Harry and sound effects for the dragon in the first challenge of the tri-wizard tournament assigns difference. Orchestral underscore for Harry channels our sympathy for his fear and determination in the perilous mission to capture the dragon’s golden egg, while sound effects for the dragon’s reptilian roars and the impact of her body against the arena stones (alternating with gasps from the spectators) reinforce her singular purpose and adversarial Otherness22. Often, we hear her sounds before seeing source and context, compounding viewer anxiety through withholding sensory information. Underscore floods the soundscape when Harry summons his broom and narrowly escapes, then sound effects take over when he loses his broom and the dragon advances, then underscore erupts triumphantly when he mounts it and flies away. When the dragon crashes into a stone bridge, falling into the crevasse below, music makes way for her plaintive roar as she plummets to perilous depths (potentially to her death), then audio-visuals move quickly to Harry’s victory claiming the golden egg. The subtext of the expendability of the animal collaborating in the tournament is ethically uncomfortable: arena sport cruelty for spectacle.

21We hear the Mer people before we see them, yet audio-visuals mix messages about how we should perceive them. When Harry submerges a golden egg in water as part of the Tri-Wizard tournament, a treble voice delivers a reverberant message in song with underwater sound effects. The voices are human, but the text form is an animal riddle, « grounded in an animal’s attested habitats and behavioural patterns23 ».

22 Come seek us where our voices sound,

23 We cannot sing above the ground,

24 An hour long you’ll have to look,

25 To recover what we took.

26Traditional animal riddles include cross-species paternalism (i.e., humans speak for non-humans), but dialogue suggests the Mer people collaborate as allies, a perspective supported in folklore. Although Harry is drawn to the Mer people by the echoes of the Mer song within the Black Lake, once close in, their voices squall incoherently through the sounds of water and orchestral underscore until one threatens Harry’s neck with a triton and tonelessly shrieks, « No! Only one! ». A shark (who is really fellow champion Viktor Krum, transformed) frightens the Mer people away with swelling orchestral brass and a predator’s roar. Then, Harry is attacked by a swarm of adversarial grindylows and sound effects rise above the orchestral score as we hear their unintelligible yelps and the sound flurry of swishing tentacles until his magic spell dispels them. That is, sound design shows alternate truths: while dialogue suggests the Mer people are equal collaborators in the tournament, audio-visuals within the lake suggest that the creatures there are collectively animal collateral.

27Lastly, Professor Mad-Eye Moody’s imposter demonstrates three unforgivable curses on a sentient spider to a classroom of students, displaying horrific intentions and outcomes without consequence to human life24. Goblet of Fire is the first to show death, and the spider’s death occurs in a series of deaths escalating to the killing of a fellow student. Moody beckons the spider from a bell jar onto his hand with a singsong, « Hellooo! …what a beauty » and then casts the Imperio curse, causing her mental anguish as he controls her movements. At first, her delicate chirps and rollicking underscore are in counterpoint to the violence of Moody’s actions, then the music shifts to minor harmonies reflecting mortal peril. Next, Moody tortures the spider physically with the Cruciatus curse; her extended painful squeals rise alongside searing brass dissonances. Hermione calls out for Moody to stop, « Can’t you see it’s bothering him? », she pleas, referring to another student’s discomfort watching (rather than the tortured spider herself). Moody casts the killing curse in front of Hermione: we hear him call out, « Avada Kedavra », a wand whoosh collides with a final spider squeal, then an otherworldly voice descends as the spider lies dead.

1.4. Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix and Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince

28The significant role of animals to further express the character of the magical realm is supported by blended combinations of underscore and sound effects in Order of the Phoenix. Physical comedy animal gags are revisited, creating continuity with the first three films. A new messenger owl motif mocks Harry’s anti-magic relatives, the Dursleys, with comedic timing. When Mr. Dursley declares, « this is the last I’m going to take of you and your [magical] nonsense! », we hear the owl’s wings (and a crescendo of tremolo strings) in the front room, the owl hits a beam with a screech, drops a letter with a thud, then falls to the floor with a louder thud and screech before flying away. We find a reprise of the non-magic cat playing with magic motif when Crookshanks bats at a dangling ear to tremolo strings and burbling woodwinds accompany with a-rhythmic meows, purrs, and an exaggerated splat for the ear itself. Songbird gallows humour returns when Prof. Umbridge sets fire to student Padma’s paper airplane bird; an asynchronous, violent end to both the gentle flute and harp supporting the bird’s audible wings and to the dulcet dialogue of Prof. Umbridge that follows. A new seasonal transition scene follows Hedwig’s pastoral flight, her screeches above a horn melody with sustained strings facilitates both height and emotion while we hear Harry’s voice-over letter to Sirius (OotP DVD 41:47). In correspondence addressing his approach to humour and animals, Hooper wrote,

To me, the definition of music is organized sound, and I have always been keen on working with the people making the effects if it was at all possible. The Natural History films that I wrote for in the nineties had very important sounds – the birds and other animals made sounds that were as integral to the film as the commentary. … My music for comedy, romance and animals is basically intuitive. Comedy is always tricky, but David [Yates] was always careful in his advice in telling me not to overdo it. Animals? Well, I have done so many scores for animals, and I love the natural world so much25…

29Outside of comedy, many audio-visual patterns change course, creating broader perspectives on the story and exploring concepts of loss. For example, the natural world is elevated through sound while evil is depicted as a violation against nature in dialogue. Music cues feature intimate, acoustic instruments such as solo flute, solo guitar, or solo piano with integrated sound effects aligning with dialogue and visuals of characters’ personal maturity and inner battles26. According to sound designer Andy Kennedy, Yates wanted to « turn down the Thunderous elements » of wand spells « in favour of warped water and feedback blips with a touch of airy whoosh », though sound effects are brought to the fore for violence and violent reckonings27. Sound combinations from both Hooper and the sound team are wide-ranging and less predictable (in contrast to the clarifying repetition and predictability of motifs of the first films), resulting in deeper, more varied narrative symbolism and emotional responses. Hooper reflected on his focus and playfulness with the task, « If we have done it well (and there was a lot of cooperation between the sound effects guys and myself) then hopefully you wouldn’t be able to tell where the music ends and the sound effects start. … I have a library of interesting sounds that I use musically in all sorts of films28 ».

30Music for animal charms affirm life with rich underscore and narrative sound effects, while music for real, tangible animals mirrors loss and death with underscore that takes over for sound effects. When students learn the Patronus charm, the powerful shield presenting as a holographic spirit animal, underscore, dialogue, and sound effects collaborate to create spectacle. The melody ascends like a rocket and cascades down sequentially by thirds, mimetically replicating the visual arc of spells and connotatively reflecting the joy manifest in the wispy leaping animals. Music energises the drama with melodic gestures and syncopated ostinati, characters declaim, « Expecto Patronum! » with whooshing wands, and animal noises reinforce each species. The polyrhythms move us, the orchestral theme with dialogue and sound for credibility signifies dynamic happiness, while the context affirms resilience.

Hooper re-contextualises the Patronus theme in Half-Blood Prince for Ron’s Quidditch tryout, elevating Ron through animal association. Musical rhythms align with visual events, and context reaffirms finding one’s inner spirit as Ron carves his identity through sport. Indeed, the sounds of Quidditch balls themselves are modelled after animals, with Bludgers like « angry animals », and the « elegant, humming bird-like » Snitch29. Then, at the Quidditch game, Hooper borrows Williams’ thunderstorm theme from Prisoner of Azkaban, embedding it in the rhythms of Stravinsky’s primal Rite of Spring (a depiction of the human animal in nature) alongside the narrative game sounds and the cheering crowd. The re-used thunderstorm melody aligns with each of Ron’s arena successes; he is a force of nature. Further, camera angles highlight the phallic imagery of his newly confident hold on the broom; Ron has found his inner beast.

In the same film I used another influence: two, in fact. Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring changed my composing for ever after I heard it at an experimental music school, at the impressionable age of seventeen; I was placed between two loud-speakers, handed the score and blasted with the most incredible piece of music I had ever heard. I came to John Williams much later but admired his scores hugely, seeing him as the master of big orchestral scores for film. Following him in the Potter series was both exciting and daunting, but when I got the chance to use his influence along with my hero, Stravinsky, I took it with both hands, and there was the music for the Quidditch match. I am particularly proud of this piece, as I find that kind of big, fast and exciting music challenging to write!30

31While Hooper’s cues tend to resolve harmonically or rhythmically with visuals, especially when inspired by folk music traditions, the cue for the Weasley twins’ fireworks spectacle leads from order to a commotion of sound and visual mayhem. Musical phrase lengths align rhythmically with visuals, reinforcing prankish humour as fireworks whizz, burst, and sparkle in sync with underscore. However, following the reel tune and three variations (i.e., AABBCCDD), audio-visuals change: a fiery dragon forms from sparks and pursues Prof. Umbridge with a roar of a beast while Carnivalesque polyrhythmic percussion takes over for orchestra until the dragon’s jaws slice closed around Umbridge. Rhythm becomes the rebellion signalling how irrational animal justice has conquered rigid human propriety. The CD track finishes with the wail of electric guitar, while in the film, the plaques of Umbridge’s rules come crashing down with narrative sound effects.

Prior to coming to the film music world, my main influences were Stravinsky, Mahler, Adams, Górecki, and then I go right back to Beethoven. (I would say that The Half Blood Prince score owes more to the influence of Beethoven than anyone else.) Otherwise, it would have to be folk music, as is evident in Fireworks from The Order of the Phoenix. …Folk music has always been a big part of my life. I started playing folk and blues on guitar at fourteen and I’m still performing it now31.

32Several cues add new perspectives on loss and death. Although death permeates the series, few deaths on film evoke emotion; rather, sounds for malevolent spells join dissonant chords, and motifs for evil, someone dies, and the story moves on. Conversely, Hooper’s folkloric funeral music and ritual for the giant spider Aragog’s death elevate life, encourage reflection, and provoke humour. Pizzicato and bowed strings in waltz time (Hooper’s code for curious situations) support dialogue about Aragog’s demise. Then, Prof. Slughorn improvises a eulogy while a Scottish style melody fills the pastoral scene. The juxtaposition of the funny waltz and the folky reverence reflects varied responses toward a deadly beast who tried to kill Harry, but who is beloved to Hagrid.

The most obvious ‘folk’ piece I wrote was for Farewell Aragog from The Half-Blood Prince. It was written to be played on the fiddle in the Scottish tradition and is inspired by the Scottish archetype - many traditional Scottish tunes have that melodic feel and lilt. The purpose was to give a soulful backdrop amongst the beautiful Highlands to a highly comic sequence where Hagrid weeps over a dead giant spider32.

33Audio-visuals for the Thestrals reframe loss as transformational and even magical. Because Harry and Luna have seen death, they see the skeletal, winged Thestrals most others cannot see pulling the Hogwarts carriages. A celeste (a code for magic) accompanies a harmonic pattern of tension and release along with the animals’ breathing and snorting. On a second encounter with the Thestrals, an atonal celeste ostinato over a slightly dissonant underscore supports intermittent Thestral chirps and squawks while Luna talks about connection with others despite feelings of isolation. As the scene ends, Luna illustrates her cheerful outlook by tossing meat to a hungry foal (a symbol of new life) which gobbles it up, supported by a swelling consonant chord. Music participates in the dramatic conversation, mimetically reflecting dialogue about disconnection with unrelated pitches, while dialogue about connection is supported with harmonically related pitches, allowing the viewer to experience concepts of connection and disconnection as well.

34Fluttering birds echo Hermione’s agitated, lovelorn emotions, another perspective on loss. We hear Hermione’s sobs before we see her when Harry finds her crying in the courtyard with twittering songbirds she has conjured, supported by a cyclic, melancholy harp tune (HBP DVD 104:05). When Ron arrives with Lavender, their dialogue disrupts the underscore. Chirp sounds come to the foreground as Hermione charms the birds to attack Ron and burst upon impact. When Ron leaves, the melancholy harp tune returns without the birds, though Harry stays to comfort her. While exploding birds in Prisoner of Azkaban reflected the harshness of nature, Hermione’s imploding birds reflect the heartbreak of unrequited love, channeled through her revenge on Ron.

35Hermione’s woeful harp follows a visual segue, passing Ron and Lavender in a stairwell, then focusing on Draco standing alone in the dark tower. Birds also follow Draco’s journey of self-evaluation through the film, and provide another perspective on loss and death. Ambient sounds of flapping wings and cooing birds frame the scene when Harry and friends spy Draco near Borgin and Burkes’ shop in Knockturn Alley (HBP 20:35). Later, when Draco enters the Room of Requirement (a room at Hogwarts magically linked to Borgin and Burkes), we hear (caged) bird sounds again (HBP DVD 133:55). When Draco places a songbird in the magical vanishing cabinet, solo piano comes to the fore as Draco contemplates her feather. The scene cuts away to Borgin and Burkes where we hear the songbird continuing to sing. However, when the bird arrives back at Draco’s cabinet, it is dead, and somber strings descend as Draco reckons with his participation in death. When the camera cuts away, we hear Draco’s sobs but don’t see him, perhaps reflecting his metaphorically un-face-able situation. Unlike other deaths in Harry Potter, however, there are no sound effects for killing curses or dissonant motifs signaling evil. Rather, music and sound collaborate to depict compassion.

It’s an odd mixture of dark and sad. Well, not sad exactly. It’s moving though. Here’s this poor boy who has been kind of pulled into this. You don’t just feel he’s really evil. So the music couldn’t be about his being evil. It’s not about that. It’s about this kid being pulled out of his depth, really33.

36Though Half-Blood Prince ends in violence and magical spectacle, the final scene elevates nature’s beauty with assistance from Fawkes the phoenix who flies and caws over the landscape supported by pastoral strings and horns.

1.5. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, I and II

37Aesthetic frills are stripped away in these final epic chapters, metaphorically representing Harry, Ron, and Hermione’s bleak experience while in hiding, isolated from the spectacle of Hogwarts. With less reliance on music and more on sound effects and ambient sounds, little underscore supports emotions or even magic. Events previously likely to have music support emphasise ambient sounds and effects instead, for instance the declamation « Expecto Patronum » (DH1, DVD 101), Ron’s splinching34 (DH1, DVD 104), the mysterious doe Patronus (DH1 DVD 136), the dragon-shaped fire in the Room of Requirement (DH2 DVD 1:00:43), and the snake attack of Snape (DH2 DVD 01:09:15). The aural effect suggests that these are natural events occurring in the magical world rather than magical events in the natural world, and also helps to streamline the lengthy films. Indeed, even the death of Hedwig, the bird whose theme song branded the franchise, has little musical/emotional response: a sound effect for the killing spell, her falling screech as she perishes, and a brief minor key phrase of Hedwig’s Theme. Nevertheless, sound effects for nature are integral to the credibility of the score. As James Mather explained, « we liked to make the passage of time stretch out using the ambience and spotted fx, the occasional woodpecker or fly past. The soundtrack allowed us to be really subtle but this made it all the more convincing and effective35 ».

38While subtle sound design supports credibility, it rarely adds new commentary. Exceptions occur for spectacle and closure; then, underscore looms large36. For instance, many sound elements play roles in the escape from Gringott’s bank, including monstrous dragon roars, diegetic rattling clankers, and a grand theme to support the friends’ escape on the dragon (reminiscent of Buckbeak’s flight, though it is unclear whether the theme signals the friends or the dragon). Similarly, music supports the eight minutes of narrative closure as Harry views Snape’s memories in the magical pensieve, including a flashback to Snape casting a doe Patronus37 revealing his love for Harry’s mother, borrowing Hooper’s « Dumbledore’s Farewell » theme from Half-Blood Prince (DH 2 DVD 01:15:45-01:23:20).

2. Nicholas Hooper’s compositional approach

39As we have seen, each collaborative team added new approaches to the musical and sound representation of animals, choosing points of continuity and departure. I focus now on the fifth and sixth films, especially composer Nicholas Hooper, who, in collaboration with director David Yates and sound supervisor James Mather, created particularly complex and nuanced relationships between underscore, narrative sounds, and sound effects. One reason for this result was their practice to incorporate music and sound early in the filming process. Hooper explains:

From my first TV film score Road Ahead (1988), I had started writing the music early. The producer, Paul Cleary, wanted music to which he could cut time-lapse sequences of building a motorway, and of traffic, and I used a minimalist style. Later, during the nineties, I wrote mainly for Natural History films and, as there was often a long post-production time, I would sometimes write the music early in the process so that the film could be edited to it. […]

I have always played the piano, both inside it and using the keys in the proper way. I play it like a composer, not like a pianist. I never conquered the classics, partly because I tended to drift off into my own music instead of practising the music in front of me! When composing into a computer on a piano keyboard I developed a style of playing that suited the sound of my different sampled instruments. So I would play and articulate a flute sound very differently from a string sound. It was a useful technique for writing example scores for directors, and stood me in good stead. At the end of the process, my electronic mixes could be used as a template for both the orchestration and the final mix.

[…] Most of the music in both [Potter] films was written before we got close to the fine cut. It made for more cohesion and less hurried decision-making38.

40Hooper's seamlessly integrated Potter scores evoke landscapes that are both real and magical, while highlighting the seen and unseen with blurred divisions between music and sound39. Rhythmic and melodic movement parallel implied narrative sounds for spectacle, critical transitions, and further, the most intense and complex narrative moments. Integrated music and sound promotes emotional impact, but for the most intense emotional moments, sensory information is eliminated, elevating primal levels of resonance; vital functions such as heart rate, breathing, balance, and orientation. Through frisson and similar techniques, we feel the sensations that result from emotion from the inside out rather than take in motivic cueing from the outside in.

41This section highlights a few scene contexts outside of animals. Hooper tends to use harmonic progressions, ostinati, and layers of sound, rather than melodic motifs to support emotions and this cohesion between music and sound. Further, Hooper’s often minimalistic approach helps underscore feel less like music and more like gestures of sound.

With David [Yates], we first really thought about using music and effects closely in the BBC Series State of Play. I remember us sitting in a pub and saying that we wanted to do something different, we wanted to take a different approach to the norm. The resulting score is a real mixture of sound effects and minimalist score (including a didgeridoo burbling in an unsettling way). The sound team recorded some of the sounds that happened naturally during filming, including a very spooky low booming sound made by tapping a lighting zeppelin. It was one of the hardest to write but most successful scores that I wrote before the Potter films40.

2.1 Opening Scene

42While John Williams delineated magical from muggle spaces with the presence or absence of music, Hooper depicts Harry’s complex experience as a magical person navigating different spheres. Combinations of silence, underscore, source sounds, sound effects and their relation to visuals and dialogue represent Harry’s nuanced experiences of his emotional, magical life. As Order of the Phoenix begins, a radio host announces a heat wave with piano music fading in and out over the orchestral title music as the camera focuses on Harry in a neighbourhood park in Little Whinging. A wind instrument mimics cicadas (a hot weather insect), then makes a transition to enhanced ambient sounds such as squeaky playground equipment before dialogue begins. Instruments enter softly on slowly changing pitches to reflect Harry’s rising anger when Dudley hurls insults at him. Elevated sound effects and tremolo strings parallel foreboding thunder clouds filling the darkening sky. When Harry and Dudley run for cover, sounds of heavy rain, running feet, and aerobic breathing continue alongside sustained airy midi sounds, until magical, malevolent Dementors descend upon them in an underpass41.

43Then, a sputtering light integrates with dissonant strings, and a low-voiced choir enters the soundscape to reflect an otherworldly malevolent presence (much as « Hedwig's Theme » entered to reflect a benevolent magical presence in the first films)42. When the Dementors attack the boys, a high-pitched violin slowly slides down a half-step interval. The interval alludes to Harry’s re-occurring nightmare of his mother screaming his name, « Harry! » (OotP DVD 03:48). The same two-note scream is produced vocally in the third film, Prisoner of Azkaban (PoA DVD 22:25), when the Dementors attack Harry for the first time on the Hogwarts train. Thus, an instrument takes over for narrative sound and dialogue, and creates continuity between films. Further, Yates requested that each spell would embody the deliverer; thus, it is especially powerful when Harry dispels the Dementors with « Expecto Patronum! », followed by a flame-thrower sound and a chorus of heavenly voices43.

44Underscore and sound effects often collaborate to imply narrative sounds. Divisions between source sounds, sound effects, and parallel orchestral and Midi scores are ambiguous when squeaky lights sputter in the echoing, faintly choral air of the underpass (OotP DVD 03:07), when doors whoosh open alongside a crescendo of strings (OotP DVD 12:45), or when the fire crackles with tremolo strings while Sirius communicates through the magic floo network, with a transition to a thunderstorm. The blurred lines delineating narrative sound from underscore may reflect for the viewer the difficulty Harry experiences distinguishing his own reality when Voldemort is influencing his thoughts in Order of the Phoenix, and likewise, when he grapples with murky truths about his mentors in Half-Blood Prince. Nevertheless, sometimes sound follows a direct metaphor for the drama: when Dumbledore casts a spell to return a disorderly room to its normal propriety; the items return to their places while a symphony of shattering sounds are played in reverse concurrently with an orchestral strings crescendo, so that all function as sound effects. The effect supports the spectacle of mystery and creates an audio-visual parallel with Prof. Slughorn’s verbal wish in the same scene to return to former glory days.

45Narrative sounds sometime create musical form. In the segue between the Burrow (where Harry, Ron, and Hermione are gathered) and Spinner’s End (where Bellatrix Lestrange, Narcissa Malfoy, and Severus Snape gather) (HBP DVD 14:45), the audible presence of fire and rain create a ternary (ABA) form with through-composed orchestra. The transition begins when the smouldering newspaper bearing a photo of Draco Malfoy crackles more loudly alongside sustained strings and rhythmic punctuation from a vintage camera flash, then makes a transition to a street deluged by rain with tension-inducing undulating string pattern where unseen characters converse in hushed voices. Then, we see the characters Bellatrix and Narcissa (Draco’s mum) approach a door, the strings return to sustained tones, they enter Severus’s home where a fire crackles, and the form tapers to a close with the snap of Snape’s own newspaper, the magical slam of the door, and the fading strings.

When we came to The Half-Blood Prince, David very specifically asked that I could work closely with the sound team, and the results were an uncanny sound score that got right inside your head. It is an incredibly atmospheric film and probably my favourite score of my entire career. The music is used subtly in the way it weaves in and out of the rest of the soundscape and, at first, I was worried that it was getting lost in places. But stepping back now and listening years later I can see that it was a masterpiece in sound design and music working closely together, not least because you don’t notice what it’s doing, you just get affected by it. It is my most cohesive score, but I take my hat off to David and the sound team for the way they used it44!

2.2 The Ministry of Magic

46Some orchestral cues function as aural representations for visual sources. In Order of the Phoenix, Harry is summoned to the Ministry of Magic after being charged with practising under-age magic. Although the stakes are high and the situation is tense, Harry is awestruck by the building itself. As Yates relays, « He's in a part of the Potter world that we as an audience and he as a character has never experienced before. . . . Suddenly [he's] in this parallel universe…45 ».

When I came to work with the director David Yates, I had got used to writing in advance of the edited film and it suited us perfectly as we liked to collaborate closely – the music being an integral part of the process of making a film. He would often play my computer-generated mock-ups to the cast and crew and also people doing the effects. The first Harry Potter piece I wrote was for the Ministry of Magic sequence in The Order of the Phoenix; it was written to a story board that showed the magnificent atrium and all the wizard-workers arriving. It remained almost exactly the same in the final film46.

47The tailored score incorporates orchestra, elevated source sounds, and sound effects to represent the experience of the magical space itself, with music and sound working as accomplices to create both rational (narrative) and irrational (emotional and magical) cueing. Given that music has signified magic throughout the Potter film series, a good audience member (i.e. one who « allows the hypnosis of film music to lower thresholds of belief ») might interpret both the presumed source sounds and the music as effortless aural aspects of the magical institution itself47.

48When Harry arrives at the Ministry of Magic, the clanking elevator and ambient dissonance make way for a new orchestral theme featuring a cyclic ostinato for strings, a majestic descant for low brass, and a sprinkle of glockenspiel. The music and source sounds follow the perspective of Harry’s visual experience: the texture rises as Harry travels through pockets of bustling activity to the opulent atrium with its grand edifices of power, then decreases in volume and changes to a more subordinate theme when Harry exits through another elevator (OotP DVD 18:45-19:35). Each layer of underscore symbolically parallels what Harry sees as he traverses the space, implying diegesis through visual alignment with mechanisms in the building. For instance, the turning ostinato for strings suggests the turning wheels of business (dozens of actual wheels turn like ceiling fans in the atrium windows); the twinkle of the glockenspiel mimics the visual sparkle of architectural ornaments, golden statues, and glossy glass panes; and the low brass descant melody parallels the din of human voices and activity heard within the cathedral-esque space. Additionally, sounds of workers’ shoes and passing conversations, as well as billowing sounds for the green flames of the floo network, and a traveling swarm of interdepartmental memos provide un-pitched temporal elements to the audio-visual spectacle. Music and sound effects work together to affect both how we see the building, and how we experience it through Harry’s eyes as a magical space48.

2.3 The Kiss

49Much as sound affects how we experience Harry’s spatial perception, it also affects how we experience Harry’s physical sensation. For instance, cues for Harry’s relationship with Cho rely on the pull of harmonic magnetism and release49, with sound effects, but not melody. Rather than framing emotion, the cues generate frisson, an emotional response « so powerful that it triggers a physical reaction. It’s a moment of ecstasy of being transported by an experience… Tingles along the surface of your skin or a chill traveling up your spine… and muscle tension or relaxation50… ». Thus we understand the emotion by what we feel, the tingling alternation of pressure and pleasure, rather than what a romantic melody might tell us as a narrative cue.

50Sound can establish, change, and dispel emotion; three cues for Harry and Cho establish attraction, accompany a kiss, and signal their fall-out51. Further, each cue incorporates ambient sounds enriching the dynamic of each interaction. 1) As Harry leaves a confrontation with Draco, the puffing of the train, like a snorting bull, reflects the tension of conflict (OotP DVD 28:23), while the expression of steam from the train signals his personal decompression (28:34). When Harry’s gaze falls on Cho (28:37), the sound of steam integrates with sustained string harmonies and the squeaky wheels of Cho’s carriage include a triangle sound (a code for magic). As Cho looks back at Harry, the turning carriage wheels parallel a repeating two-bar harmonic cadence (played by strings, with a celeste ostinato) alternating between a C half-dim.7 harmony and a Bb major harmony (ii half-dim7 to I). 2) Then, when Harry and Cho converse in the Room of Requirement, the repeated two-bar cadence returns with strings and celeste (ii half-dim7-I). The pattern falls to minor chords (iv-i) as they discuss the death of Cho’s former boyfriend. When the two re-focus on each other, mistletoe descends from above, blossoming with imagined sounds for fresh growth. The harmonies ascend in major (Ab then Bb chords, VII-I) then return to the original two-harmony alternation (like aroused breathing) with greater volume, increasingly sustained rhythms, and a rumbling of timpani as the two engage in a long kiss, resolving satisfyingly to a broad tonic chord. 3) Later, when the relationship breaks down, the harmonies also lose their magnetic hold, progressing from the C# half-dim. 7 to the (diatonic) II chord, then the (parallel minor) i chord, without supporting ambient sounds to elevate chemistry (OotP DVD 01:26:59).

Example 2. Three statements of Nicholas Hooper’s harmonic motif for Harry and Cho in Order of the Phoenix as described above. Personal transcription from the film.

51Hooper describes his process as intuitive,

Some of the most popular sequences in both Potter films, say for Cho’s kiss and Ginny’s kiss, are completely instinctive. I couldn’t tell you why or how I made them work. The use of guitar in « Ginny kissing Harry » was a lovely chance to record my guitar in Abbey Road One (I was a professional guitarist before I got into film music)52.

52When Ginny kisses Harry, sounds emphasise the intimate and natural rather than the orchestral and magical. Further, sounds are removed, rather than added, to draw us into the fundamental frisson experience. In the Room of Requirement, Harry and Ginny hear fluttering from a cabinet; a bird flies free, singing, when Harry opens the door. Thus, a source sound provides a metaphor for un-caging the characters’ own feelings. A gentle, harmonically cyclic solo guitar theme enters with sustained orchestra strings as Ginny tells Harry to close his eyes. When Ginny leans in to kiss Harry, the guitar theme falls away and the shimmery string harmonies crescendo into their kiss, an aural metaphor for adrenaline. When the kiss ends, the guitar theme returns and Harry opens his eyes. Harry’s closed eyes focus his senses to feel the kiss; likewise, when the guitar melody falls away, it narrows our attention on the shimmery strings metaphor for the kiss. While in Williams’ score for Prisoner of Azkaban, underscore imitated the sound of the body for animals (e.g., beating heart, pounding hooves), Hooper’s scores elevate physical sensations for human characters as well. After the kiss, the guitar returns along with the bird’s singing53.

2.4 Sirius’s Death

53Loss and death accompany Harry’s journey, yet filmmakers often used sound to play down death scenes (eg, cueing narrative progress rather than emotion), thus protecting viewers from the emotional ramifications of violence and loss54. The first time that music draws us into the emotion of a character death occurs in the fifth film when Sirius Black, Harry’s godfather, is killed in front of him (OotP DVD 01:57:00). In this scene, similar to Ginny’s kiss, emotional intensity is conveyed by eliminating sound elements rather than integrating them or increasing their volume55.

David and I continued to work the music closely with the sound design in other projects after [State of Play], and when we came to Potter we discussed closely how the music might lie with the action. In « The Death of Sirius », when Harry is devastated, he made the decision to have just music and no sound from Harry – it felt so much more moving that way56.

54Following an action-packed fight scene with dialogue, sound effects, and an energetic underscore, the background music stops, Bellatrix Lestrange casts a killing curse on Sirius Black with dialogue and sound effect, then all dialogue and magical sounds stop to make way for an airy sound effect as Sirius slips backward through the veil of death. Then, underscore, a string melody that seeps seamlessly into the background as Sirius fades away, takes over for both dialogue and sound effects. Visuals return to Harry’s shocked face and we see him screaming as Remus Lupin restrains him, but we don’t hear it57; underscore covers all would-be dialogue or sounds from their struggle. Selectively, we hear Harry sob in between the visuals of screaming, followed by Bellatrix’s chuckle, but no other dialogue or sound effects. Harry breaks free from Lupin, we hear Bellatrix’s reverberating sing-song taunt, « I killed Sirius Black », then dialogue, sound effects and underscore return58.

55This is the first time a musical theme usurps source sounds and dialogue in this way. The irrational use of audible music (making dialogue inaudible) conveys a metaphor for Harry’s overwhelmed emotions in the face of tragedy. We don’t just see that Harry is sad, we experience an imbalance of aural and visual resources that compromises our emotional defenses and knocks our logic off balance as well. Further, the gradually descending, unraveling three-part texture of the music provides an emotional perspective of time that is in counterpoint to the disorienting, manipulated speeds of the visuals. The theme is rhythmically misaligned before it aligns as Harry comes to terms with a truth too difficult for words. By mapping codes used for animals onto Harry (e.g., elevated sounds of sobs but not his words, and using musical metaphors for the state of the body), we see beyond the surface level, witnessing one of the most difficult moments of Harry’s humanity.

56Similarly, when Dumbledore is killed at the end of Half-Blood Prince, it is a loss for Harry that is too deep to hold supported by a lament bass, a « music of a deep darkness emanating from some cold, black well »59. Although the music immediately accompanying Dumbledore’s death is restrained, music for the elegiac acknowledgement of the death spills over, usurping dialogue and other narrative sounds. Much as in Harry’s grief for Sirius, only Harry’s sobs are selectively brought forward.

In The Half-Blood Prince I wrote and recorded « In Noctem » early on in the filming. This was because it was intended to be sung by the Hogwarts choir in a sequence where Snape was pacing up and down, preparing himself to kill Dumbledore. We recorded Queens College Choir, Oxford, at Abbey Road Studios, and then filmed the scene with Warwick Davis conducting and the choir of actors miming (with me standing behind but not needed much as Warwick was so good). As it turned out, that sequence was actually cut to make space for much tenser music as the Death Eaters arrived to witness Dumbledore’s death at the hands of Malfoy. But the strange part of this was that we used a part of « In Noctem » to go with Dumbledore’s appearances and his sequences with Harry. It became, as David said, the DNA of the film60.

57Thus, while the imbalance between underscore and dialogue reinforces the emotional fracture Harry experiences, the culminating use of Dumbledore’s music also offers closure for the penultimate film chapter.

Conclusion

58Combinations of music and sound profoundly affect film aesthetics and the experiences of hearing integrated sounds allow us to understand narratives through feeling rather than prescriptive cueing. The five distinctly different collaborations across the eight-film Harry Potter series carved new ways of seeing, hearing, and caring about Harry’s journey while also displaying different strategies for achieving story cohesion, series continuity, and novel insights. Particularly when we examine the music and sounds for animals, we find audio designs that intermediate between the known and unknown, distilling themes and subtexts, and revealing inner conflicts. In going deeper than simply cueing the story of animals and for humans in animal bodies, these examples show us how music and sound help us perceive emotions, feel sensations, and experience the story as bodies with heartbeats, breath, and shivering skin. Sound designs for animals relay stories beyond simple description about the best and worst of humanity. The collaborators for the fifth and sixth films (Yates, Hooper, and Mather), especially, sought out ways to integrate music and sound in order to carry viewers more deeply into the story, often feeling the story more deeply in our bodies. Importantly, the integrated outcome was due to intentional collaboration61.

Though I couldn’t say with certainty after all this time as to what was calculated in every single cue and what just happened between myself, the director and the sound and FX team, [it was] a place that I inhabited in the film-music world that was exciting and innovative. The word » Team » is very important as I look back, and the Potter team of producers, sound effects team, film editor, dubbing mixer, and David, along with all the people who cared for my music in Hollywood, helped and supported me hugely in making the two scores62.

59Their efforts help the narrative to transcend the specifics of Harry’s journey so that we see, universally, both the distressing aspects of humanity as well as those aspects offering deeper hope and connection. Ultimately, the approach helps us to see ourselves within the narrative, inclusively as thinking, feeling, and sensing beings, with heights and depths of emotion.

Notes

1 Danijela Kulezic-Wilson describes how integrated soundtracks can resonate with viewers at a tactile, sensory level, which she identifies as sensual, and further, a consensual engagement between viewer and the sonic flow. Danijela

Kulezic-Wilson, Sound Design is the New Score: Theory, Aesthetics, and Erotics of the Integrated Soundtrack, Oxford University Press, 2019, pp. 8-9.

2 The Dark Arts (evil magic) include three powerful curses that are considered so sinister and unredeemable that their use carries the strictest penalties in the magical world: the Cruciatus curse causes unbearable pain, the Imperio curse causes complete control over the victim, and the Killing curse causes instant death. In the fourth film, these unforgivable curses are demonstrated on a spider.

3 Ibid.

4 Steve Larson’s work explores how metaphors of movement help us understand how we are thus moved by music, for instance in Steve Larson, « Something in the Way She Moves – Metaphors of Musical Motion », in Metaphor and Symbol, vol. 18, n° 2, 2003, pp. 63-84.

5 Sean Williams, « The Sea and the Sky: Shapeshifting and Transformation », forthcoming, 2022.

6 Eugenio Bolongaro, « Calvino’s Encounter with the Animal: Anthropomorphism, Cognition and Ethics in Palomar », in Quaderni d’italianistica, vol. 30, n° 2, January 2009, p. 109.

7 Eduardo Kohn, « How Dogs Dream: Amazonian Natures and the Politics of Transpecies Engagement », in American Ethnologist, vol. 34, 2007, p. 5.

8 Bolongaro, « Calvino’s Encounter with the Animal », p. 110.

9 Margo DeMello, « Introduction », in Margo DeMello (ed.), Speaking for Animals: Animal Autobiographical Writing, London, Routledge, 2013, pp. 1-14.

10 Jamie Lynn Webster « Creating Magic with Music: The Changing Dramatic Relationship between Music and Magic in Harry Potter Films », in Janet K. Halfyard (ed.), The Music of Fantasy Cinema, London, Equinox, 2012, pp. 193-217.

11 Ibid. This cue often includes celeste, harp, and choral voices; key instruments used to convey the supernatural, as if they are the sound effects of the magic sphere itself. Subsequent composers adapted the theme with different melodic intervals, rhythms, harmonies, and instrumentation, symbolizing varied depictions of magic with audio-visual alignments.

12 Ibid. Although various published scores are available, they often simplify harmonies for learners and conflate melodies and harmonies from the different films. Hedwig’s Theme, in particular, changes significantly between films, yet this is not always represented in the popular published versions.

13 Ibid.

14 Thomas Veatch, « A Theory of Humor », in Humor, the International Journal of Humor Research, vol. 11, n° 2, 1998, p. 164. Veatch proposes that humour is an emotional response when the « subjective moral order » has been violated.

15 Transcriptions and further analysis are included in Jamie Lynn Webster, The Music of Harry Potter: Continuity and Change in the First Five Films, University of Oregon, PhD dissertation, 2009, pp. 542-544.

16 Jamie Lynn Webster, « Musical Dramaturgy and Stylistic Changes in John Williams’s Harry Potter Trilogy », in Emilio Audissino (ed.), John Williams: Music for Films, Television, Celebrations, and the Concert Stage, London, Brepols, 2018, pp. 253-273.

17 David Huron, Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology of Expectation, Cambridge, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2006, 34. While a treble choir is used for Prisoner of Azkaban, a deep male choral sound accompanies the only appearance of the Dementors in Order of the Phoenix.

18 Editors used bird sounds from the Cornell University’s Macaulay Library at the Lab of Ornithogy. Krishna Ramanujan, « From “Harry Potter” to ‘The Incredibles”, blockbuster movies turn to Cornell Lab of Ornithology for blockbuster sounds », in news.cornell.edu, consulted June 2021.

19 Mike Thornton, « Sound Design: What Does Magic Sound Like? A Look at How the Harry Potter Films Redefined the sound of Magic », in pro-tools-expert.com, consulted May 2021.

20 A fuller analysis of how these segments enrich temporal and spatial transitions is included in Jamie Lynn Webster, « Musical Dramaturgy and Stylistic Changes in John Williams’s Harry Potter Trilogy », in Emilio Audissino (ed.), John Williams: Music for Films, Television, Celebrations, and the Concert Stage, London, Brepols, 2018, pp. 253-273.

21 This topic has relevance with recent reader discussions about how the author’s biographical social biases may have played out in the narrative. Despite Rowlings’ spoken intentions, reader discussions on online forums cite several examples where racism, classicism, ableism, sexism, and LGBTQ+ unfriendly narratives play out in the Harry Potter books.

22 That is, music for Harry allows him to be complex and nuanced while sound effects for the dragon do not allow the same.

23 David Herman, « Animal Autobiography; Or, Narration beyond the Human », in Joela Jacobs (ed.), Humanities, vol. 5, n° 4, 2016, p. 82. The song is sung by the composer’s daughter, Abigail Doyle. The lyrics are condensed from the book.

24 As the spider in the scene is computer generated, one could argue that viewers may not see consequence to animal life either.

25 Personal correspondence, copyright held by Nicholas Hooper, 2021.

26 This is in contrast to the ways large scale orchestra aligned with fantastical construction of the magical landscape and society in the early films. Film critic Roger Ebert and others noted how the fourth film, Goblet of Fire, marked a turning point in the series, departing from the magical delights of the first films as characters grow and leave innocence behind. However, I posit that sound design specifically aligns with narratives of personal growth beginning in the fifth film, Order of the Phoenix. Roger Ebert, Roger Ebert’s movie yearbook 2009, Kansas City, Andrews McMeel Pub., 2009.

27 Jake Riehle, « Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix Exclusive Interview with Sound Designer Andy Kennedy » in designingsound.org, consulted in May 2021.

28 Anonymous, « Grammy-nominee, Nicholas Hooper, makes musical magic in Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince », in snitchseeker.com, consulted in May 2021.

29 Sven E. Carlsson, « The Sound of magic: Sound design of Harry Potter 1 », in filmsound.org, consulted in May 2021.

30 Personal correspondence, copyright held by Nicholas Hooper, 2021.

31 Ibid.

32 Ibid.

33 Anonymous, « Half-Blood Prince composer Nicholas Hooper Talks Style and Score in New Interview », The-Leaky-Cauldron.org., consulted in May 2021.

34 Splinching is a painful and potentially life-threatening physical injury that can occur during an incomplete teleportation.

35 Miguel Isaza, « Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part I – Exclusive Interview with Supervising Sound Editor James Mather », designingsound.org, consulted in May 2021.

36 Indeed, a major task of the last two films is to reinforce continuity and create closure.

37 A Patronus is a magical guardian in the shape of an animal.

38 Personal correspondence, copyright held by Nicholas Hooper, 2021.

39 This is in contrast to the scores by John Williams which elevated magic and the scores by Doyle and Desplat which elevated realism.

40 Ibid.

41 Danijela Kulezic-Wilson characterises this sort of scene as having a balance of auditory and visual immersion, when the sound design comes from the found sounds of characters’ settings and actions. Danijela Kulezic-Wilson, Sound Design is the New Score: Theory, Aesthetics, and Erotics of the Integrated Soundtrack, op. cit., p. 104.

42 The first significant iterations of Hedwig’s Theme in the first film coincide with repetitions of magical owls bringing letters from Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry into the Dursley family’s non-magical space.

43 Mike Thornton, « Sound Design: What Does Magic Sound Like? A Look at How the Harry Potter Films Redefined the sound of Magic », in pro-tools-expert.com, consulted in May 2021.

44 Personal correspondence, copyright held by Nicholas Hooper, 2021.

45 Originally from an interview on MTV.com, in LeakyCauldron.org, consulted in February 2009.

46 Personal correspondence, copyright held by Nicholas Hooper, 2021.

47 Claudia Gorbman, Unheard Melodies: Narrative Film Music, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1987, p. 5.

48 This approach has historical roots, for instance, in Gottfried Huppertz’s original score for Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927), especially in scenes showing the underworld workers.

49 Theorist Steve Larson defines metaphors for musical motion in terms of physics, following principles of gravity, inertia, and magnetism. Steve Larson, Musical Forces: Motion, Metaphor, and Meaning in Music, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 2012.

50 Ainsley Hawthorn, « Have you ever had a “Skin Orgasm”? These ephemeral sensations say something about your personality—and your brain », in psychologytoday.com, consulted May, 2021.

51 These follow Cohen’s laws of control, change, and closure. Annabel J. Cohen, « Music as a Source of Emotion in Film », in Patrik Juslin and John Sloboda (eds.), Music and Emotion, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 263-264.

52 Personal correspondence, copyright held by Nicholas Hooper, 2021.

53 This is different from the way Alexandre Desplat adds in full orchestra for Ron and Hermione’s kiss in Deathly Hallows – part II.

54 For instance, when Harry’s affable schoolmate Cedric Diggory dies, underscore draws attention away from the grief of the witnesses in order to prioritise narrative progress Jamie Lynn Webster, The Music of Harry Potter: Continuity and Change in the First Five Films, University of Oregon, PhD dissertation, 2009, p. 409.

55 Although it is not uncommon for filmmakers to elevate music score above sound effects for dramatic death scenes, it is not an approach that is found in the many other onscreen deaths in Harry Potter.

56 Personal correspondence, Nicholas Hooper retains copyright, 2021.

57 Claire Henry postulates the connection between the silent scream and shock responses. Claire Henry, « The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo: Rape, Revenge, and Victimhood in Cinematic Translation », in Berit Åström, Katarina Gregersdotter, and Tanya Horeck (éd.), Rape in Stieg Larsson’s Millennium Trilogy and Beyond: Contemporary Scandinavian and Anglophone Crime Fiction, London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, pp. 175-192.

58 The wand battle that follows was the « only section in the movie without music so it gave a chance to let the sound effects rip ». Jake Riehle, « Harry Potter and The Order of the Phoenix—exclusive Interview with Sound Designer Andy Kennedy », designinsound.org, consulted in May 2021.

59 Barnaby Martin, « The Music that Links Dumbledore’s Death to Bach and Radiohead », in https://www.youtube.com/c/ListeningIn, consulted January 2022.

60 Personal correspondence, Nicholas Hooper retains copyright, 2021.

61 Danijela Kulezic-Wilson notes how intentional collaboration between composer, director, and the sound team is a critical component of the new practise of integrated scores. Danijela Kulezic-Wilson, Sound Design is the New Score: Theory, Aesthetics, and Erotics of the Integrated Soundtrack, op. cit., p. 7.

62 Ibid.

Citation

Auteur

Quelques mots à propos de : Jamie Lynn Webster