Preliminary remarks

It has not been easy to write and reflect upon the 14 months of research I completed in Sudan some 50 years ago1. Put simply, and not intending to state the obvious, it would be impossible to replicate today. Our ways of thinking, approaches to risk and degrees of access have all changed. Moreover, despite globalisation, countries have pulled apart. Where one could travel relatively freely before, all manner of new obstacles and doubts now exist. In many ways, the world seems more distant and politically polarised than it was.

The challenge has been to reflect on my fieldwork without recourse to nostalgia. The past is no better or worse than the present—it is simply different. How to highlight that difference is the challenge. Important here is the unique human attribute of consciousness, especially of existing or being in the world, so to speak. In terms of historical differences, the changing material conditions, behavioural expectations and intellectual horizons that shape being in the world are the focus here.

The essay has three interconnected parts. First is my mid-1970s doctoral fieldwork in Maiurno, a large village on the banks of the Blue Nile, about 320 kilometres south of Khartoum. With the anti-colonial struggle for independence still resonating, the 1970s were the tail end of several decades of relative openness and ease of international travel. A global liberal hour, if you will. Second is the time when I returned to Sudan in 1985 as field director for Oxfam, a British non-governmental organisation (NGO). This period of “NGOisation” was a key moment in the shift toward new forms of international engagement that in many ways marked a turn away from earlier ways of knowing the world. Third is my short retrospective visit to Maiurno in 2014, 40 years after I first went there. By then, following years of sanctions, Sudan and the West were politically at odds. Getting an entry visa and travelling outside of Khartoum was difficult.

Circulation versus connectivity

In order to make sense of this history, the contrast between “circulation” and “connectivity” has been used to frame my argument. At first glance this may seem an unusual contrast. In English, to “circulate” and “connect” are often used interchangeably as they are commonly thought to have similar meanings. However, not only are they different, but an antagonism can be argued to exist between them2 (Duffield, 2019). The difference lies, on the one hand, between the concrete and often unpredictable milieu created by the free circulation of autonomous people and things, which has been the predominant condition for most of human history. On the other hand is the power to technologically connect across what are otherwise abstract and unbridgeable geographic, temporal and social divides, be it through the printing press, sailing ships or satellites.

To put this in another way, there is an antagonism that deepened with modernity between the “concrete” space-time of circulation and the “abstract” space-time of connectivity (Lefebvre, 1991). The ability to technologically connect across abstract space-time has historically functioned as an apparatus of security in relation to autonomous circulation. One example is early-modern urban planning. As Foucault argued, the risks posed by free circulation are central to a liberal conception of security (Foucault, 2007, p 34, 41). The laissez-faire principle of circulation—to allow people to move and things to happen—calls forth a logistical apparatus of policing that, using technologies of connectivity, prohibits “bad” circulation as a function of promoting the “good”. Architecturally improving the circulation of people and things—of travellers, goods, vehicles, clean water, light and air—while policing the flow of disease, sewage, crime and political agitation was the defining challenge of modern urban design.

While antagonistic, historically, the technologies of connectivity have always assisted circulation, as, for example, the steamship and nineteenth-century European migration to America. The trend within modernity, however, has been for connectivity to greatly increase its power to index and recall movements, times and destinations. A brief present-day example of the security function of connectivity concerns the international movement of people and things. In opposition to the unstoppable flow of migrants and refugees attempting to evade interdiction in order to fulfil their life-claims in Europe, stand the security technologies of border and maritime policing, forced encampment, biometric cross-referencing and what are in effect international refoulement agreements. Besides impeding “bad” migration, however, electronic borders also ease the flow of favoured passport holders and allow the rapid movement of goods within global supply chains. However, given that such “good” movement is now digitally recorded, it is also subject to corporate and state monitoring, and thus potential veto. It too falls short of free circulation.

If technologies of connectivity operate to police the circulation of people and things, it follows as a general proposition that the more connected the world, the less free circulation. Enhanced by Covid-19, the rapid digitalisation of all walks of life, and the advances in corporate and state surveillance thus enabled, defines the policing power that connectivity now exerts over circulation. In understanding our present predicament, the antagonism between circulation and connectivity is more informative than the more conventional contrast between “hierarchy” and “network”, which invariably celebrates the claimed liberatory power of the latter (Ferguson, 2018). Given the corporate interests that dominate social networking technologies, for example, such contrasts are inevitably self-serving.

In any given period, the relations and specific technologies that define “circulation” or “connectivity” are different and historically contingent. The antagonism between circulation and connectivity has shaped successive regimes of technology capture, social redundancy and, importantly, the never-ending resocialisation of human populations. I will argue that becoming remote, the theme of my essay, denotes the new condition, or conventional expectation, for being in the world. While a simplification of a more nuanced situation, the shift from living face-to-face to interacting face-to-screen is indicative. Historically, becoming remote has often been experienced as a loss of sociality. A dis-connection, if you will, from earlier, more autonomous modes of social interaction and circulation. It is in relation to this shift that my essay is framed.

A relative openness to the world

To begin, a few words on the relative circulatory openness of the 1970s are important, especially given the current restrictions regarding migrants and refugees. My doctoral fieldwork was possible because of two things. The great mid-twentieth-century anti-colonial struggles had temporarily weakened imperial control and, in the former metropoles, the unprecedented social mobility of the time. In Europe, this brief loosening, so to speak, before the neoliberal counter-revolution, is usually seen in relation to the rise of the welfare state and Fordist-forms of national capitalism. It also witnessed a brief surge in the international circulation of newly independent peoples and radical anti-imperial ideas. In Britain, it was a time of primary immigration from the former Caribbean and Asian colonies. While these immigrants were never welcome, the flow could not be legally stopped until well into the 1970s (Duffield, 1988).

Besides a loosening of international circulation, my fieldwork was dependent upon the social mobility encouraged by national capitalism. Born in 1949 in the small Black Country town of Tipton3, near Dudley, in what is now the West Midlands, my father was a foundry worker and my mother worked at the local post office. We lived in a Victorian back-to-back terraced house with no bathroom or inside lavatory. Hemmed in by a public park, railways, canal, factories and gas works, the daily background noise was the rattling chains and bangs of metal fabrication. At night, it was the melancholy clashing of shunting railway trucks. An early formative memory was the pungent foundry smell of burnt oil, sand and iron filings that clung to my father’s work clothes. From an early age, the factory wasn’t for me.

Because of what is now called dyslexia, I failed the 11+ school selection examination. Instead of a grammar school, it was a boy’s secondary modern that beckoned. Whereas grammar schools trained managers, the secondary modern socialised factory and service workers. Another key memory was the metalwork teacher telling a story about a professor and a secondary school boy. A professor stands by his stalled car, bonnet open, staring blankly at the engine. Along strolls a technically minded secondary modern boy who spots the problem and soon waves the grateful professor on his way. Like factory work, fixing things for my betters was thereafter a non-starter.

Reflecting the international circulation of the time, within a few years of my family leaving Tipton in 1963, first-generation Bangladeshi immigrants were living in the same terraced houses. I came to know some of them in the 1980s when working in local government. Tipton, however, would have its 15 minutes of fame in 2001. The first British subjects killed in the post-9/11 allied invasion of Afghanistan were not soldiers, they were second-generation British Muslim supporters of the Taliban. The Tipton Taliban, as they were called, were three young men who, having been captured, were rendered and held in Guantanamo Bay for several years. They grew up in the same houses and played in the same streets as I had a generation earlier.

My own chance of escape came in 1968 when, having got the necessary entry qualifications at Dudley Technical College, I became a sociology undergraduate at Sheffield University. However, having a practical background, I had little understanding of what sociology was. The idea to go to university had come through a General Studies tutor at the Technical College who had a sociology degree. His lectures on Vietnam, the Cold War and racism were, quite literally, “sense making”. Whatever it was, sociology promised a more exciting world than the one I knew.

In 1968, UK universities, as those elsewhere, were in a state of revolutionary turmoil. One was immediately caught up in sit-ins, anti-Vietnam demonstrations and the occupation of the London School of Economics. My introduction to anthropology was through an irreverent and charismatic veteran of the Spanish International Brigade, Frank Girling. As an Oxford anthropologist studying the Acholi, Frank had been declared persona non grata by the Ugandan colonial government for spending too much time on the wrong side of the fence. His anarchic Comparative Social Structures course had no formal organisation or curriculum. Apart from accompanying Frank on anti-racist demonstrations, his students read and discussed the latest radical publications as they appeared—Althusser, Foucault, Lévi-Strauss, Marcuse, Walter Rodney, Angela Davis and anything else by the Black Panthers.

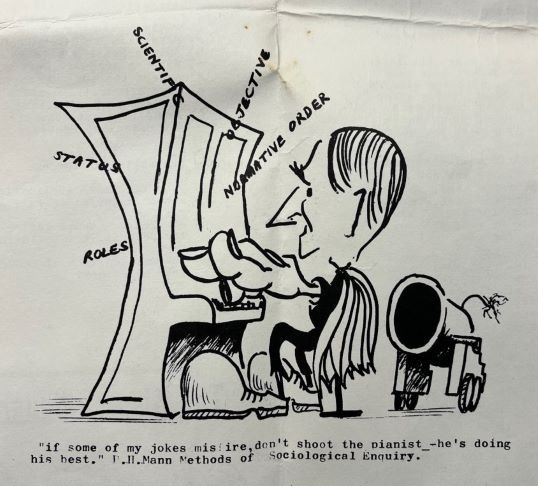

Besides the boycott of classes and bookshops, it was a brutal time of critical practice involving the relentless denunciation of petit-bourgeois lecturers, colonial anthropology and, as the cartoon drawn for a university rag suggests, a determined push-back against empiricism and behaviourism within the academy. While, as a generation, we neglected capitalism’s destruction of the environment, we learnt in this hard school that the Third World was pioneering a new path to socialism from below (Marcuse, 1967). The international system was a circulatory whole, and liberation struggles in one country helped those in others. National liberation was thrust to the centre of anthropology. The new anthropology was not about rescuing the discipline or making it more inclusive—what is called “decolonisation” today. It was more about burying it through solidarity with the revolutionary struggles of the oppressed.

Getting to Sudan

Having completed a Master’s degree in African History, I spent the academic year of 1972 at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London learning to speak Hausa. Besides Marxism, the structuralism of Claude Lévi-Strauss had been a strong influence, especially his path-breaking work on how oral societies produced elaborate classificatory systems, spatial architectures and bodily designs through a rigorous vitalistic interrogation of nature. My intention had been to go to northern Nigeria to collect and decode Hausa folktales. The hypothesis was that such material would contain hidden understandings and resistances to capital penetration. However, owing to bureaucratic delays within Nigeria, I had to change plans and, unexpectedly, ended up in Sudan. Settled since the colonial period, there are many Hausa-speaking communities there, where such Westerners are known collectively as “Fellata” by the Sudanese Arabs.

In the 1970s, getting an overseas research grant was much easier than today. Student numbers were fewer, funding was available and institutional risk aversion had yet to materialise. You more or less just applied. The departmental administrator even completed the paperwork. There were no PhD probationary requirements, and while students would interpret things their own way, the expectation was that one would leave as soon as the grant arrived and be away for some time working in a remote setting. Given that the airmail letter was then the main means of international communication, the notion of “remoteness” was elastic.

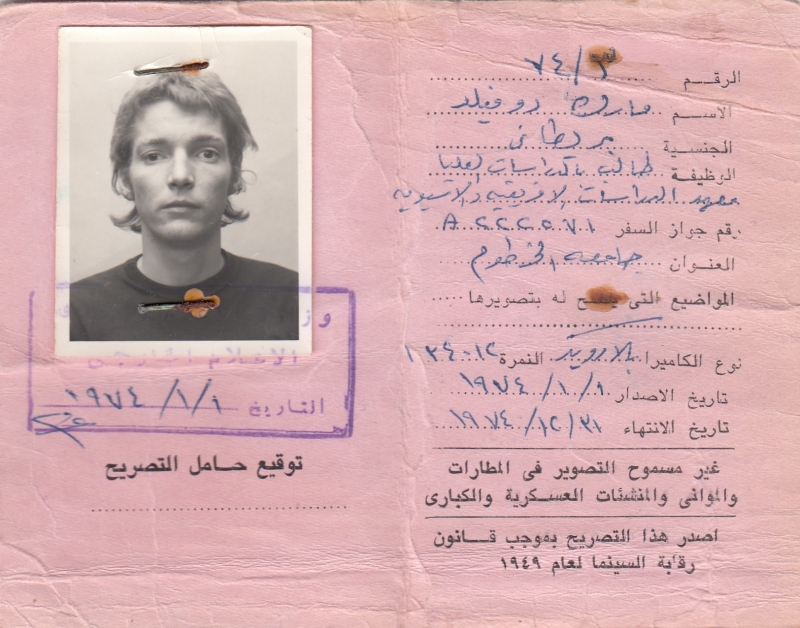

As for official Sudan clearance, before structural adjustment, the NGO invasion, Islamism and decades of military rule, the government still had a public administrative capacity. In October 1973, I wrote to the Institute of African and Asian Studies at Khartoum University requesting academic affiliation. Within a couple of months, all formalities had been completed. I landed in Khartoum on Christmas eve, the first time I’d ever been in a commercial aeroplane and, apart from a Paris school trip, outside the UK. Three weeks later, on 16 January 1974, I arrived at Maiurno. I was 24 years old and, working alone, would spend the next 14 months there. From the initial airmail letter to arrival, the whole process had taken less than four months.

Apart from opening a bank account, getting permits and archival work, the three weeks in Khartoum were spent considering possible field sites. That it would be Maiurno was not certain in advance. Given the heritage of slavery and ambiguity surrounding black Muslims, the Fellata are widely regarded as second-class citizens in Arab Sudan. A rarity in 1974, there was a “Fellata” undergraduate, who happened to be from Maiurno, studying at Khartoum University. I had read about this Blue Nile settlement. It was founded at the turn of the twentieth century by Fulani aristocrats and their Hausa followers fleeing Britain’s colonial conquest of the Sokoto Caliphate in northern Nigeria. In 1974, Maiurno was home to Sultan Abu Bakr Mohammed Tahir. Now deceased, Abu Bakr was then around my own age. As a direct descendant of the original founder, he was the nominal representative of the Blue Nile Fellata settlements.

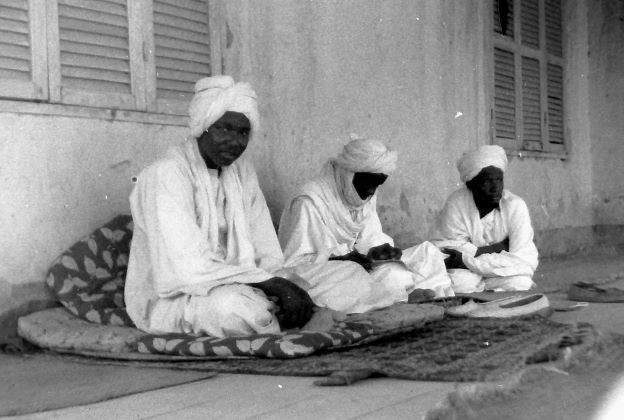

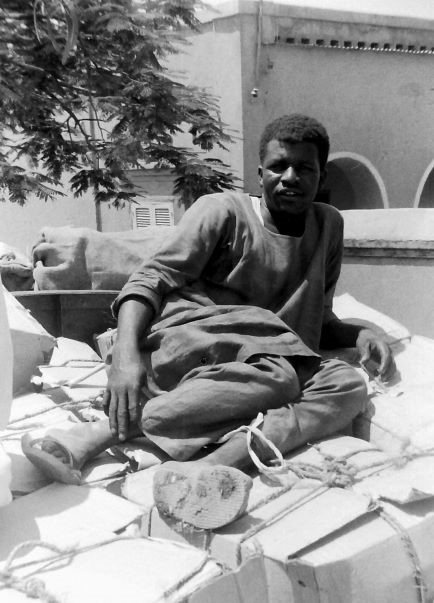

Plate 4

Sultan Abu Bakr Mohamed Tahir (first from the left)

▪ Credits: Mark Duffield. All rights reserved.

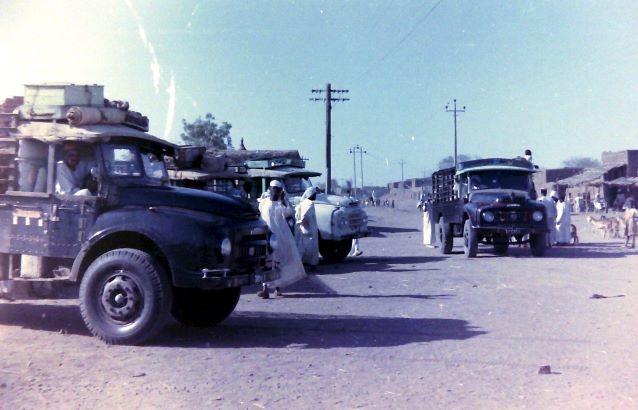

My student acquaintance had given me a letter of introduction to give the Sultan. Maiurno was then, at best, an exhausting 12-hour journey in an open-sided bus. A tarmac road extended only halfway. The rest was completed on winding bush roads which became impassable during the rainy season. Appearing unannounced, and arriving at Abu Bakr’s door with a letter, a suitcase and speaking hesitant Hausa, my arrival aroused much curiosity. That first night, unable to sleep, listening to the crickets outside—to quote my diary—I felt utterly “lost to the world”.

Fieldwork in Maiurno

Once part of Sudan’s colonial Native Administration, the Sultan’s family had seen better days. By 1974, the reception rooms of his compound, where I would stay as a guest, had fallen into significant disrepair. One ate with the unmarried men and youths of the household and bathed using a bucket. Maiurno was a large riverside settlement with a central marketplace. Constructed predominantly of mud and thatch, besides a junior school and some market buildings, there were only a handful of brick-built compounds which mainly belonged to lorry merchants. Except for such buildings, there was little electricity. Typical of rural Sudan, water was drawn from wells, or else, direct from the river and sold by the jerry can.

There were no telephones. Even if there had been, neither my family, nor that of my girlfriend, possessed one. Outside communication, even with Khartoum, was facilitated by letter. For the UK, a five- or six-week letter cycle was involved. Getting mail required opening a Post Office (PO) Box at Sennar, the nearest town, which was a two-hour round trip by lorry. Because of the hassle and delays of concrete time-space, visiting the post office became a weekly event. It was not time wasted, however. As with everything one did, it was part of being there. You met people on the lorry or in the town, formed acquaintances, learnt things. Getting the mail became inseparable from exploring, dropping by for a chat, or drinking tea with market traders.

Letter writing was therapeutic and receiving post a delight. However, given the time lag, you either dealt with problems yourself or through the friends and contacts you had made. This “dependent autonomy”, so to speak, was an effect of what has been called the “dignity of distance” (Sloterdijk, 2013, p. 13). This is not an attribute of connectivity. It is more associated with the concrete space-time gulfs that existed in the age of sailing ships. A faint echo of this dignity, however, could still be heard in 1970s rural Sudan. It imposed a dependence upon one’s hosts that the student had little choice but to embrace. It impelled levels of social immersion that would be difficult, maybe impossible, to replicate in today’s connected world.

Fieldwork in independent Sudan was an individual sink or swim exercise. There were no formal methodology courses for anthropology students, and university affiliation was just a formal requirement. There was little local support. Aspirants who failed to leave Khartoum within a month probably never would. Guidance came from one’s supervisor together with other qualified academics. My three key advisors were all women anthropologists, only one of whom had Sudan experience. This was Wendy James who had worked among the Uduk in southern Blue Nile. You were expected to blend in by living modestly. Learn the language, adapt to the climate, eat local food and stay a year to observe the seasons. Advised to take introductory gifts, mine were fragrant soap, American cigarettes, photocopies of historic Hausa texts and a Polaroid instant camera to gift photographs.

In terms of methodology, the now unfashionable idea of society as an interconnected whole was pressed into service. Concerned with social contradictions and antagonisms, the practical challenge was, as far as possible, to get to know directly a cross-section of the host society. Back then, however, Maiurno was more socially conservative than today. As a guest, one was necessarily confined to the company of men. Conscious of this limitation, and developing a compensatory interest in changing marriage practices, I knew farmers, lorry drivers, labourers, merchants, teachers and fakirs: rich and poor, educated and illiterate, young and old. When not interviewing or transcribing—or visiting other Hausa-speaking settlements—the daily routine was to circulate between appointments, acquaintances and friends. In between, one walked or cycled through the fields talking to farmers, picked up gossip at the lorry stop, or passed the time of day with market traders and artisans.

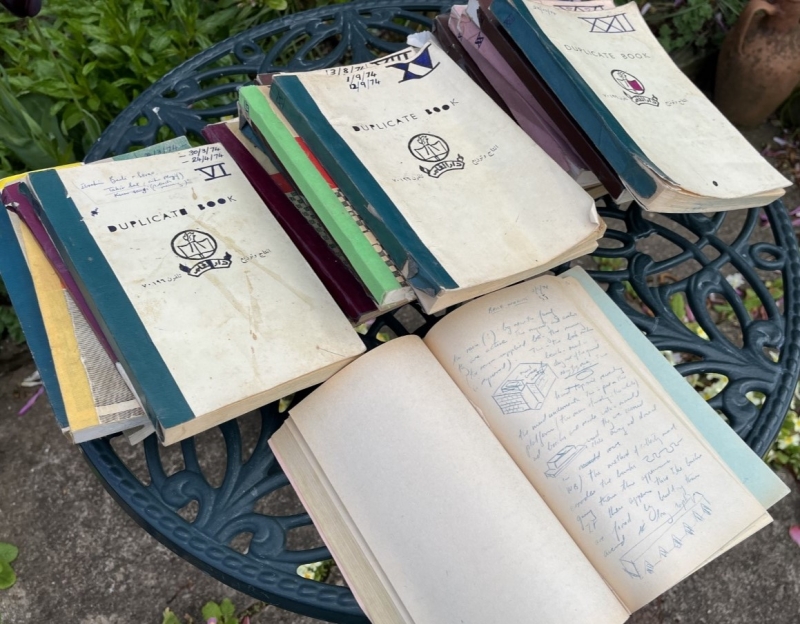

Carrying a notebook was essential. Every evening, the day’s interviews, casual conversations, observations and speculations were written up in duplicate books. The carbon copies furnished a daily narrative record, while the top copies, kept separately, were eventually used for rough subject-based sorting and cataloguing. Although time-consuming, the discipline of regular writing-up encouraged quiet contemplation. It helped uncover gaps, formulate conjectures and refine questions for future work.

Knowledge derived in this way is distinct from abstract data-based information. Respecting the concrete space-time of circulation, participant observation anticipates interruptions and expects delays. It stops the daily flow and creates a space for people to speak and account for themselves. Fieldwork cannot be rushed. Questions and insights reveal themselves slowly. In contrast, data is only useful to the extent that it can be quickly made operational (Rouvroy, 2013). As the product of behaviour that has been converted into abstract signals and alerts, data informatics is the fuel of remote management. We will return to this later. Here, it is sufficient to say that rather than allowing people to justify themselves in person, the conversion of behaviour into a series of profiles is tantamount to the disavowal of direct human engagement. Profiling is the opposite of ethnographic fieldwork.

Reading my notebooks today, an innocent openness, even naivety, haunts the narrative. Absent is any sense of the anxiety-inducing “underdevelopment is dangerous” trope that hardened with the War on Terror (Dillon & Reid, 2009). For the 1970s radicals, the Third World was neither “backward” nor “doomed by nature”. Right or wrong, it was an agent of history pioneering a better future. One was necessarily attuned to the voices of disadvantaged interlocutors. Unlike some aid agency practices encountered later, while undoubtedly helped by being a Hausa-speaking Englishman, talking to people in Maiurno was never an exercise in entitlement or privilege. Working alone, respecting privacy and confidences, it was more a case of building trust over time.

As much effort was spent explaining my world as asking about theirs. Maps were drawn in the sand to show the unschooled Sudan’s geographical location. Work and politics in Britain, together with marriage and burial customs, were regular topics. If asked, I did not conceal my own lack of religious belief. Reflecting an accommodating rural Sufism (unlike the Wahabism then spreading in urban areas), rather than being offended, the common reaction was a friendly bemusement at my obvious naivety. Belief was also a hook for discussions of comparative religion and an opportunity for the occasional mischievous joke about mishaps at British crematoria.

At his suggestion, over several weeks, I tried to explain Marxism to an internationally renowned Maiurno fakir. In return, among other things, he described the psychological mind games he used to straighten out the wayward youth of Saudi Arabia’s elite. Important here was his self-awareness of being a black African credited with magical powers in an Arab society. He was interested in Marxism because, in Jafar Numeri’s Sudan, it was sometimes mentioned in the media. Given the circles he moved in, having a passing familiarity was useful. Speaking Hausa, I’m unsure who gained the most but, as with all good fakirs, his social acumen and sharp intelligence were never in doubt.

Over time, many acquaintances became friends, and some friends became confidants. Given my age and temperament, socially, the young tractor and lorry drivers exerted a gravitational pull. Participant observation blurred into the camaraderie of expeditions to Sennar, raucous evenings playing cards, leg-pulling and laughter. By being there, they changed my life, just as “Mr Mark” changed theirs.

In terms of burying anthropology, however, my fieldwork did not contribute to world revolution. By the mid-1970s, even if it had existed, this possibility had passed. Based on large-scale mechanised farming and the Blue Nile lorry trade, a new rural elite had supplanted Maiurno’s colonial feudal aristocracy. A self-sufficient peasantry was rapidly decomposing into the spreading wage economy (Duffield, 1981). In retrospect, my visit coincided with the high point of independent Sudan’s autonomous rural development. Neoliberal structural adjustment, famine in the North and the rekindling of civil war in South Sudan would soon change that. All these events helped usher in a new set of conditions for being in the world.

With Oxfam in Sudan

Having completed my PhD, after several jobs, I returned to Sudan in 1985 as Oxfam’s field director. Employing some 200 people, mainly local staff, Sudan was then Oxfam’s largest overseas aid operation. In terms of changing world-views, the four years spent there were formative. What has been called “NGOisation” was rapidly becoming entrenched (Mann, 2015)—that is, initially at least, the transfer of state-based public welfare responsibilities to international aid agencies. In Sudan, largely due to its relative speed, borrowing a phrase from Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, this process has also been called the “fantastic invasion” (Large, 2012). Flying the flag of humanitarian relief, from having little presence in Northern Sudan in 1983, within a couple of years, more than a hundred international NGOs were registered in Khartoum. Those that were operational were mostly found in Darfur or the Red Sea region. Due to war, apart from government towns, the South was closed.

The fantastic invasion marked a sharp break with the concrete knowledge of my doctoral fieldwork. It was a key moment in the emergence of a new apparatus of connectivity and the early foregrounding of capital’s current cybernetic episteme. Practically overnight, the “humanitarian imperative” had swept away earlier modes of language-based knowledge and causal thinking. Categories like “capitalism”, “peasantry” and “exploitation” disappeared to be replaced by registers of “poverty”, “vulnerability” and “empowerment”. Dismissing the mid-1980s famine as having any connection with the crisis of subsistence and expansion of capitalism, NGOisation pioneered new depoliticised forms of theory and practice based on “complexity” thinking (Booth, 1985). As an intense period of resocialisation, or, perhaps better, cognitive reformatting, the fantastic invasion was a disorientating process to step into.

In terms of understanding the world, the invasion practised the narrow empiricism of multiple competing variables. It was a triumph for the one-dimensional behaviourism that the 1968 student generation had fought against. Rather than disaster being inseparable from capitalism, as radicals had previously thought (Meillassoux, 1974), it was now outside and incidental to it. Things like “drought”, “civil war” or “colonial legacies” vied equally with “cash cropping”, “lack of political representation” and “gender inequality” to produce a multicausal “complex emergency” (Cater, 1986). Since no single cause predominates, no overriding responsibility can be assigned. No single person, party or interest group can be held to account. The idea of a “complex emergency” shaped the practical diplomacy of NGO humanitarian intervention. It enabled aid agencies to operate in the midst of a civil war without, so to speak, having to mention it.

Complexity thinking is an example of neoliberalism’s celebration of functional ignorance. Apart from immediate experience, the wider world is beyond human understanding. Hence, the epistemic importance of markets. “Famine early warning” is an example of necessary ignorance in practice. It is also indicative of the shift from concrete to abstract space-time that gathered momentum during the 1980s. With the collapse of subsistence, rural dispossession and the spread of capitalism out of the picture, famine became a purely behavioural issue. Rather than seeking political solutions, what people actually do when they starve and how they personally or collectively cope or adapt to disaster became more important (De Waal, 1989). The fantastic invasion naturalised famine. Indeed, even civil war, which has been a permanent feature of the Horn of Africa since the 1970s, would become a “natural” event.

In the 1980s, hungry households in Darfur collected wild foods and sold livestock, while some members migrated in search of work. As a result of these coping strategies, the market price of livestock and labour fell due to oversupply, while that of grain increased because of growing demand. The aid industry developed technologies to capture these behavioural and price fluctuations among populations now understood “biopolitically”—that is, abstractly through the complex and indeterminate economic, social and environmental variables that now define life-chances.

Rather than a critique of the way we live and share the world, humanitarian emergencies were converted into a matrix of abstract data signals and alerts generated by behavioural change. Stripped of history, an “emergency” became a veritable “black box”. Other than being complex, there is no need for aid workers to understand its causes. All that is necessary is that they accept that certain signals and alerts telegraph an increased probability of system breakdown. It is argued that such early warnings will then trigger timely humanitarian intervention.

That “early warning” as a tool of humanitarian response has never worked is not my concern. More important is that the shift toward complexity-thinking grounded in functional ignorance took place before the global generalisation of computer use. Collecting data signals and behavioural alerts in 1980s Sudan was a labour-intensive analogue affair. Using pen and paper, local aid workers visited rural markets to record prices, drove great distances to interview community representatives, and worked out trends with hand-held calculators. Centralising and compiling the results took weeks.

Despite its pre-machine origins, however, the logic of early warning—using past relational patterns to predict future events—is the same as that underpinning what, decades later, would be called “surveillance capitalism” (Zuboff, 2019). Indeed, this predictive logic underpins digital governance generally. My main point, however, is that the fantastic invasion was part of a wider preparatory change, or resocialisation, during the 1980s in our mode of being in the world. Helping pave the way for the seamless digital revolution, famine early warning is just one example of the analogue embrace of connected abstract space-time before the arrival of the machines that would lock in this move a decade later. Moreover, turning emergencies into standardised sets of what would become increasing remotely-sensed data signals (satellites, mobile phones, etc.) prefigures later developments in the aid industry, helped by austerity and increased risk aversion—that is, the trend to manage disaster zones remotely through arms-length technologies of connectivity (UNOCHA, 2013).

Return to Maiurno

If the end of the Cold War heralded a New World Order, it is one where international space, riven by border fences and international treaty derogations, has been hyper-securitised by novel logistical controls on the circulation of people and things. It has been striated into fast, slow and stop lanes. In January 2014, almost 40 years to the day of first arriving, I returned to Maiurno for a four-week retrospective visit. In 1974, one entered through the front door, so to speak. This time, it was necessary to go around to the back.

Having recently retired, I was able to step outside the now homogenised and widely policed space of UK social science research (Pardo-Guerra, 2022). Travelling in a private capacity, one didn’t need to negotiate the university’s increased risk aversion, meet unrealistic ethics committee requirements, follow third-party security advice, or purchase overpriced insurance. With just travel and subsistence costs, the trip could be self-funded, thus also avoiding having to compete for an effectively non-existent research grant. Nor was it necessary to wait for sabbatical leave or incur the penalties for taking time off.

The securitisation of international circulation, however, is a collective process. Reflected in a range of initiatives, governments of the Global North and South now act together to restrict movement. Attention is often drawn, for example, to European Union efforts to limit migrant flows from Africa by subcontracting border control responsibilities to Sahelian and Mediterranean countries. Rather than just a response to external pressure or financial inducement, however, these arrangements build on the fact that, for some time, such countries have also controlled internal circulation more rigorously than they did.

During the 1980s, international aid agencies in Sudan could still move on the ground. As a counter-move, the state regulated access to short-wave radio, then the only means of long-distance communication. With the spread of mobile telephony and inability to control the electronic atmosphere, the state now restricts terrestrial movement. Following years of Western sanctions, by 2014, getting an entry visa, and government permission to leave Khartoum, were problematic. Compounded by risk-averse home institutions, many international aid workers and consultants, even if they wanted to, found it difficult to move outside the capital.

Ironically, it was the same former student who had originally introduced me to Sultan Abu Bakr, and was now a prominent academic, who provided the Sudan embassy in London with a personal letter of invitation. He also arranged accommodation in Maiurno. A hotelier friend from my Oxfam days secured a tourist travel permit that extended as far south as Sennar, just short of Maiurno. Today, Maiurno can be reached in under six hours on a tarmac road in an air-conditioned bus.

Unlike the 1970s, Maiurno now has a police post. Early on the morning following my arrival, I was picked up from my lodgings by plain-clothes security and driven to the police HQ in Sennar for questioning. Fortunately, I had known Maiurno’s present Omda, or local governor, when he was a teenager. We had often eaten together in the late Sultan’s compound. While explaining to the police that I’d lived there in the past, he interceded by telephone to vouch for me, thereby avoiding me the near certainty of having to return to Khartoum. This enhanced security presence, plus the more managed nature of research, visa restrictions, institutional risk aversion and heightened levels of personal anxiety, all add to the difficulty of travelling to places like Maiurno today.

Maiurno has grown in size. Mud and thatch have given way to mainly brick buildings and, running the length of the settlement, the main throughfare has been surfaced. The majority of compounds now have electricity and piped water. Supplied by Chinese capitalism, TV sets, washing machines and refrigerators are commonplace. The market has stalls catering to new consumer tastes and services, like juice bars and mobile phone repair shops. There are even three-wheeled “tuktuks” for local hire. Importantly, Maiurno is less socially conservative than it was. The girls’ school is well-attended and, in contrast to the 1970s, women are publicly evident and visibly engaged. Some men attributed this to the popularity of Egyptian TV soaps which often feature strong female roles. Whatever the case, in a few weeks, it felt as if I’d spoken to more married women, and seen more private living quarters, than during the 14 months of my PhD fieldwork.

Local neighbourhood mosques, once modest mud-built structures, have evolved into imposing, electronically amplified brick and plaster buildings. The proliferation of telecom masts and ubiquity of mobile phones is equally noticeable. Indeed, the masts stand taller than the minarets. Electronic connectivity means you can be in more than one place at once. While the bandwidth was relatively narrow in 2014, you could still check emails within minutes of arrival. The dignity of distance that still existed in the mid-1970s, and the social immersion it once necessitated, had now disappeared. No more slow days collecting mail from the post office, and casually dropping by for tea and gossip. Out of connectivity, however, new challenges have emerged.

In 1974, there was a tangible material gap between Maiurno and my hometown of Dudley. Surrounded by working factories, for the latter, it was a time of full employment and rising consumer affluence. In contrast, Maiurno had little electricity and drinking water was drawn direct from the river. After years of austerity and social deprivation, now etched in bodies and clothes, Dudley today is visibly rundown. If not boarded up, the town is given over to thrift stores, betting shops and fast-food outlets. At night, without much imagination, the bus station has the desolate feel of a refugee transport hub.

If a development gap existed in the 1970s, it has now narrowed. Dudley has declined, so to speak, while Maiurno has risen. Where the life-chance advantage now lies is ambiguous. In a blurring of former Global North–South divisions, the experiences of the people of Dudley and Maiurno have, if anything, drawn together. They are both subject to governments that rule through executive power, security protocols, restricting freedoms and censorship. While access to university education has expanded in both places, degrees have been devalued. For the majority, education fails to translate into meaningful employment. In Dudley and Maiurno, compared to their parents’ generation, the increased precarity of the young is widely acknowledged. The globalisation of flexible and informal labour markets means that, for the global majority, work does not adequately support social reproduction. With the appearance of several voluntary-sector foodbanks in Dudley, evidence of Britain’s internalisation of famine relief for the working poor, the gap has narrowed further.

While Dudley and Maiurno have drawn together, the reasons are dissimilar. Resulting from deindustrialisation and austerity, Dudley’s journey has the feel of a generational collapse in living standards. The case of Maiurno is different. Given the West’s sanctioning of Sudan since the 1990s, its visible improvement is an example of what could be called “actually existing” development—that is, a degree of material progress that has occurred without Western assistance and, indeed, against the apparent intentions of donor governments and multilateral agencies.

Actually existing development in Sudan is an example of the political push-back against Western interests occurring in many parts of the Global South. It must also be acknowledged, however, that the material progress in central riverain Sudan, where Maiurno lies, is inseparable from the violence that has, for example, befallen Darfur—just as the decline of Dudley must be set against the visible concentration of wealth in Greater London and oligarch off-shore bank accounts. Such violent and diverse geographies of dispossession and accumulation have engineered the contradictory drawing together of Dudley and Maiurno.

The era of permanent emergency that began with the ending of the Cold War suggests two things. While bracketed by new extremes of wealth and poverty, there is an emerging majority world where life-chances have drawn together and, consequently, experience is becoming comparable. I began this essay by stating the impossibility of replicating my doctoral fieldwork. Besides the restrictions on movement, the explanation was framed in relation to the antagonism between circulation and connectivity, and becoming remote through the replacement of concrete knowledge with abstract data informatics. The more connected the world, the less free circulation. It can now be added that as a security apparatus captured by capital, connectivity works to neutralise the potential radical opportunities created by an immanent majority world. Indeed, perhaps because of the political threat to the status quo of a growing communality of global experience, corporate social media relentlessly entrenches a toxic politics of identity, division and cultural relativism.

As for Maiurno in 2014, while some of my friends had died, I was again reliant on the support and company of those still there. We picked up old stories, jokes and adventures as if yesterday. In the last analysis, maybe friendship is what it was all about.

*

Tragic Sudan

On 15 April, 2023, the ongoing crisis in Sudan deepened significantly. Widely derided as a war between avaricious generals, much more is at stake. With the collapse of a unitary government, the danger is one of morphing into a fragmented territory contested by ethnically aligned military actors. In this respect, Sudan is not an exception. It would be joining the likes of Libya, Somalia and Yemen. In terms of knowing what is actually going on, for years Sudan has been a growing blank space for outsiders. What we know today is from bloggers and a few brave Sudanese journalists.

To be sure, we are not seeing “state failure”. It is the intensification of a violent extractive economy that now reaches deep into the social bedrock. Historically, Sudan was a largely self-sufficient agro-pastoral society. But this society has been an escalating disaster zone since the 1970s. Put simply, neocolonialism destroyed self-sufficiency and turned the old reciprocities between farmers and herders into a relation of permanent war. Violence, moreover, is not only an economic relation, there is also an affinity between merchant-capital and cost-reducing warlike behaviour. From the beginning, military actors have shaped the social civil war between farmers and herders into a cruel extractive economy. Land clearances, looting and killing have supplied regional markets in Egypt and the Gulf states with growing quantities of land, gum Arabic, gold and, not least, livestock.

Either by eviction or liquidation, the men with guns have eliminated Sudan’s democratic opposition. Remnants of the aid industry are holed up in Port Sudan, the de facto new capital, where they will probably remain. As good as any conjecture, was the disappearance of sheep to steal the ultimate cause of the present inter-military fighting? On a surer footing, Sudan’s neighbours and the Gulf states are jockeying for geopolitical advantage and continued market access. Not least, the millions of inhabitants and migrant workers associated with Gulf’s ongoing construction of new urban phantasmagoria will still need cheap food. As for the western powers, as long as Russia is kept out and migrants in, whatever the internal political settlement, it will be accepted.

The Sudanese are a kind and hospitable people. Khartoum was always a polite and safe city. We must shed a tear for Sudan.