Applauses and Banners, Horns and Fireworks: Tracing the Sonic Expression of French Social Movements During Lockdown

Alessandro Greppi et Diane SchuhDOI : https://dx.doi.org/10.56698/filigrane.1424

Résumés

Résumé

La pandémie du coronavirus a transformé les paysages sonores des luttes sociales et politiques à travers le monde. Dans notre article, nous souhaitons proposer l'étude de leurs expressions sonores en France lors du premier confinement, de mars à juin 2020. L'année 2019 a été une année de grandes manifestations, qui ont culminé avec le mouvement des Gilets jaunes, les protestations des travailleurs de la santé et de l'université, et les grèves de masse pour protester contre la réforme des retraites. Comme le veut la tradition en France, ces manifestations ont été marquées par l'utilisation massive de chants, de musique et de rythmes. Le confinement a interrompu ces formes d'expression, mais de nouvelles manifestations sonores de la dissidence ont rapidement émergé pour échapper aux restrictions imposées par le COVID-19 : banderoles de protestation, applaudissements pour les soignants, klaxons de voitures contre la gestion de la crise par le gouvernement, concerts improvisés, percussions de casseroles et feux d'artifice pour protester contre les conditions de vie difficiles dans les banlieues. Quelles autres expressions sonores politiquement conscientes le confirment a-t-il induites en France ? Nous tentons d'y répondre par la documentation et l'étude du son, sous l'angle des espaces privés nouvellement occupés au profit d'expressions publiques, en vue de délimiter les futurs modes de participation et de dissidence politiques.

Abstract

The coronavirus pandemic has transformed the soundscapes of social and political struggles across the globe. In our article, we would like to propose the study of their sonic expressions in France under the first lockdown, from March to June 2020. The year 2019 was a year of major demonstrations, which culminated with the Yellow Vest movement, the protests of health and university workers, and mass strikes to protest pensions reforms. As per tradition in France, these demonstrations were marked by the extensive use of song, music, and rhythm. The lockdown interrupted these forms of expression, but new sonic manifestations of dissent quickly emerged to elude COVID-19 restrictions, including protest banners, claps for caregivers, car horns against the government’s handling of the crisis, improvised concerts, casserole percussion, and fireworks to protest harsh living conditions in the suburbs. What other politically conscious sonic expressions has the lockdown induced in France? We attempt to respond through the documentation and study of sound, under the lens of newly occupied private spaces for the benefit of public expressions, with a view to delineating future modes of political participation and dissent.

Texte intégral

1. Introduction

1In France1, strikes and demonstrations marked 2019 and the beginning of 2020. Several social movements emerged and generated transport strikes, teacher strikes, and large demonstrations in opposition to several bills, including the pension reform bill. The demonstrations against pension reforms began on 5 December 2019 and grew to include several million citizens2. The Yellow Vests – a popular movement protesting for economic justice, initiated by the rising costs of fuel – joined the movement on 7 December, and higher education and research personnel in January 2020. At that time, shortly before the confinement, a wide range of protest songs (including “Le Chant des partisans3”, “On est là4”), brass bands, traditional Brazilian percussion ensembles called batucadas, choirs, screams, sound systems, and political slogans, all gave rhythm to France’s political and social life5. The social movement seemed to never stop. However, in the face of the accelerating health crisis related to the spread of COVID-19, the French government decided abruptly to confine the country on 17 March 2020. The question arose as to how to continue to express disagreement with public policies, when the very possibility of protesting was effectively prohibited by the lockdown. How can the voices of protest be listened to and heard when the vast majority of its actors are confined in their homes?

2In this article, we analyse the sonic responses to this question. For this study, we conducted a virtual ethnography by collecting visual and sonic documents online. We followed activist groups on social media and analysed their practices: how did they gather and what codes did they reference while shifting the avenues of the protest from the street to the windows and balconies? We studied how they created alternative venues of expression across visual and sonic dimensions. We also analysed how new and traditional media chose to report and portray these practices. Departing briefly from virtual ethnography, we also conducted daily recordings for 15 days outside our windows during lockdown, focusing on the 8:00 pm clapping event – a social and sonic practice that was established in France and other countries during the first lockdown. Which alternative avenues of expression did these confined struggles find during the lockdown? Did the lockdown inspire new sonic materials and approaches that facilitated dissident expressions? How did these movements position themselves in relation to the 8:00 pm applause for caregivers’ ritual, also initiated during the lockdown?

3For clarity, we will use the term soundscape in this article to refer to the sonic and acoustic environment of the places and milieux we are analysing. With reference to Murray Schafer (1977), we are reading the term with the actualization of the notion of milieu theorized by Augustin Berque6. Each place we analysed has specific sonic characteristics that were induced by sonic events circumscribed in a specific time frame (applause, protests, fireworks, etc.). These sonic events were overlaying the usual sonic environment, which was itself also affected by the lockdown. These events reconfigured the soundscape, creating a sonic bursting in an otherwise calmer soundscape. For the sake of simplification, we will use the term soundscape as a reference to what could be called a punctuating sound environment overlaying the usual soundscape.

4We trace the transition of the protest from the street to the window by focusing mainly on the sonic dimension, but we will start by analysing an artefact that facilitated the shift between visual and sound: the protest banner. To this end we collected banner photos taken by activists and shared on social media with specific hashtags. By noting the musical and sonic aspects of these banners, we observed how windows and balconies singularly replaced public forums during the lockdown. We then consider the places of these sonic events, particularly during what became the daily 8:00 pm applauses. Having recorded the applause on a daily basis, we chose one representative excerpt focused on the socializing aspects of this event, and compared this situated expression with other recordings gathered online. We went on to examine the appropriation of this social practice for purposes of protest. Finally, we analysed how the use of horns, sirens and fireworks allowed for the appropriation of a counter-space of appearance – framed here in response to Hannah Arendt’s “space of appearance7”, that comes into being wherever people participate in the realm of the political – by invisibilised and excluded populations. We also analysed a collection of recordings made by the parties concerned and shared on social media for the purpose of reclaiming their own narratives.

2. #CortègeDeFenêtre: When the Songs of the Protests are Displayed in the Window

5After several months of struggle and demonstrations, France found itself confined on 17 March. The demonstrators had to reorganise. The ban on public gatherings made the task difficult. The chants of the union processions stopped. The confinement became then, for some, an opportunity to reuse the tools, sounds, and musical materials of traditional demonstrations in a critical and creative way. It was then a question of rethinking the struggle on another scale. During the lockdown, demonstrations organized in Paris or in other big cities took place on a more local scale. New solidarities were created with neighbours and through political events with a micro-local dimension. On social media, the hashtag #CortègeDeFenêtres tagged banners of the demonstrations that were hung from windows during the lockdown. The cortège de tête (leading procession), now confined, expressed itself at the window instead. The phenomenon is socially not insignificant. In Europe, where demonstrations traditionally take place in the streets, windows and balconies have historically taken on a role of substituting the public forum. At the border of the public and private spheres, balconies and windows are full of social significance8.

6The balcony, in particular, has been a military device in the Middle Ages, a stage for authoritarian and fascist powers in the twentieth century, and a promise of social progress and emancipation for the working classes in post-World War II Europe9. The windows of the #CortègeDeFenêtres served for their part as political flags for claims that fell within wider anti-government protests. These windows participated in a reinvention of notions of public space during the lockdown.

7The impact of these actions was amplified through social media. Indeed, social media is becoming a virtual space of interaction for political expression. During the lockdown, these ways of expressing were amplified by the impossibility of gathering outside. We can argue then that the sociology of social struggle, here displaced to balconies and windows, forms part of a broader digitization of balconies, leading to a virtual conversion of the formal architectural reality of the balcony. This phenomenon existed prior to the lockdown and reminded us of the way Julian Assange used balconies to stage public appearances from the Ecuadorian Embassy in London10. Notably, in France this appropriation of a private space for political purposes can lead to prosecution11.

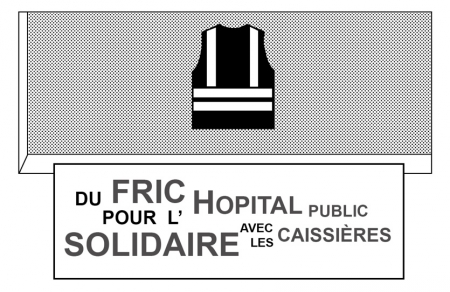

Figure 1: the slogan reads “Money for the public hospital, solidarity with the cashiers12”. Illustration based on a photo from a collaborative collection of protest banner photography collected on Twitter under the hashtag #CortègeDeFenêtre.

8We were able to observe the content of these messages, consisting of slogans chanted or sung during demonstrations (see Figure 1). We recognised that the makers of these banners were either reproducing the same banner slogans as those seen during the protests, or painting the slogans that were only chanted. Thus the slogans, sometimes written in verse, privileged the expressiveness of form. Sound effects were translated by the use of rhymes which facilitate oral and rhythmic transmission. The poetic dimension is marked on canvas.

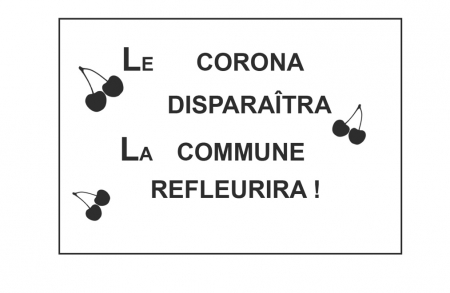

Figure 2: The banner reads “The corona will disappear; The commune will bloom again13”

9The songs evoked are from the culture of struggle. The Paris Commune14 is referenced here by the cherries on the banner shown above (Figure 2) and the song “Le temps des cerises” (The time of cherries). Written in 1868, this song is associated with the Commune because its author, Jean Baptiste Clément, was a Communard who fought during the Semaine sanglante. Its lyrics have been interpreted as a metaphor of a lost revolution15.

10In general, most slogans evoke struggles that preceded the lockdown and which were adapted to the medical-lexical field related to the fight against COVID-19. The slogans are critical of government policy. Examples include:

Macron don’t leave your poor behind

Pangolins against capitalism

Money for the hospital not for capital!

Let’s kill the capitalism that kills us! Let’s save the public service that saves us!

Euros for the hospital

Money! Money! For the public hospital!

Broken public service = danger

our lives are worth more than their profits

save lives not the economy

2018: macron cuts 4172 hospital beds

Never forgive never forget.

11Other slogans drew parallels with the notion of the police state:

All

Covid-19

Are

Bastards

Support for hospitals16

12Here, the acrostic form was used. The slogan refers to the acronym All Cops Are Bastards. This anti-police slogan was popularized during the British miners’ strike of 1984-198517. Here, the confined slogan can also be read as ACAB, Support for Hospitals. These anti-police slogan tries to camouflage itself under an anti-COVID-19 phrase by playing on semantic ambiguity.

13Other slogans assimilate anti-state positions to the lockdown:

14ACAB however 18

15Covid-19 Everywhere

16Justice nowhere

17Solidarity with Caregivers, delivery people, cashiers, construction workers…19

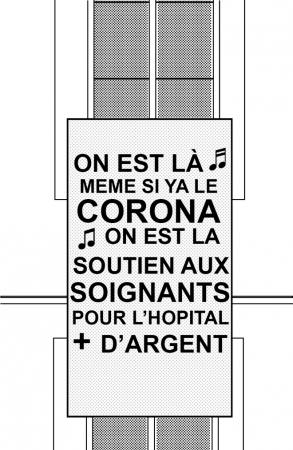

18The punctuation and the exclamation points, remind us that we are in the domain of listening and shouting. On one banner, musical notes have even been drawn (two sixteenth notes and two eighth notes), making explicit the association between the two senses, visual and auditory, which is apparent in this approach (see Figure 3). Beyond the solfegic precision, it recalls a fight song. More than reading the banner, it is necessary to sing it.

Figure 3: the banner reads “We’re here even if there’s corona; We are here; Support for caregivers; For the hospital; + money20”

19If, confined, the demonstrators could no longer sing together in the streets, they could write their songs and slogans in capital letters. They revived these songs, in an almost mournful silence, in order to continue the struggle, as if the survival of the expressions of their protest depended on this music. It is enough that the passer-by or the neighbour reads and/or sings them so that the message is disseminated. In this way, despite being confined, the demonstrations continue through the multiplication of individual initiatives, at the window or at the balcony. The appropriation of window and balcony spaces for the political purpose of continuing the demonstrations took place in a context that has provoked other confined collective demonstrations. Thus, these banners were hung in parallel or in opposition to another ritual which was set up from the first day of the confinement: the 8:00 pm applause.

3. The Applause at 8:00 pm: The Rhythms of a New Confined Socialization

3.1 Appearance of clapping

20Inspired by their Italian neighbours who had already been confined for two weeks, the French began to applaud at eight p.m. to honour the work of caregivers considered as being on the front lines of the fight against COVID-19. According to Aymeric Renou21, a journalist at Le Parisien, the first applause was heard in France on Tuesday 17 March, the first day of lockdown. Depending on the neighbourhood and the city, the applause and the wishes of solidarity were extended to workers who continued to go out to pursue their missions essential to the life of the community, in a territory where the virus was active. Invisibilised workers, cashiers, delivery men and women, garbage collectors, and construction workers, found themselves in the media spotlight for a moment. The ritual was well established and would last throughout the confinement (from 17 March to 11 May 2020). Shortly before eight p.m., the French would stand at their window or balcony to applaud the essential workers. The event lasted five, ten, or sometimes 15 minutes. As the month of March progressed, this event, for many the only social moment of the day, transformed into a party.

3.2 What is clapping?

21Applause is the sound of two hands clapping together. In his article “Applause: A Social Behaviour,” sociologist David Victoroff notes that applause is a social mark of satisfaction and approval22. He also notes that clapping involves a “contagious” movement23, and the expression of a “conventional and institutionalized” gesture24. Finally, he notes that we are here in a gesture of “communication and language”25. Thus:

The manifestations of admiration and approval are thus regulated by the group to which the individual belongs. It is the group that determines the circumstances in which applause is recommended, tolerated or forbidden, and sometimes even regulates its intensity and duration. The applause is thus a social expression of approval, not only as a collective demonstration, but also and especially as a conventional demonstration26.

22With these definitions in mind, let's listen to some excerpts from the 8:00 pm applause.

3.3 What clapping means in times of confinement

23We can listen to an excerpt we recorded on 10 April 2020, on rue des Hautes Formes in the 13th arrondissement of Paris:

High Formats recording XIII (6 :30)

24From 00:37, we hear a single person clapping quite slowly (almost one beat per second), it is not yet 8:00 pm. Finally, at eight (one minute later), the applause starts in the distance, then a tambourine starts its percussion (at 01:20 approximately), and at 01:37 we hear a yelp siren27. At about 03:50, we distinctly hear a rhythmic percussion, probably by means of a stick and a plastic or metallic surface; in any case it seems to be a homemade percussion instrument. We also hear the tambourine trying to keep up with this rhythm by beating along with the beat. At the end, the tambourine takes over and we again hear the slow clapping of the beginning. From 04:53 on, we hear non-musical socializing.

25In addition to the rhythmic and sonic dimension of the applause, the confinement highlights the social dimension of the applause. Indeed, as the confinement progressed, the ritual of applause became a moment of re-socialization, especially between neighbours. Every evening, after about five minutes of applause, the inhabitants began to converse and to exchange news with one other. In this recording, from 04:53 onwards, we can hear: “enjoy your weekend”, “tomorrow, an aperitif!” or “we'll have some delivered for everyone”. Listening to emblematic recordings of the soundscape of this neighbourhood at 8:00 pm during the confinement28, allows us to highlight the conventional character of the ritual. Originally conceived as a tribute to the essential workers, this ritual becomes a moment of sharing and musical communication. Indeed, the different applauses answer each other in imitation and develop rhythms whose effect seems to palliate the solitude and the silence of the confinement. The applause is a conventional rite, but it does not make consensus. The hypocrisy that some can detect in the message conveyed, and the social and political manipulations of the gesture have given rise to numerous criticisms, with some seeing this practice as a way to “buy a good conscience29”.

26Thus, beyond the musical interpretations that one might make, applauding in times of confinement is also a way of situating oneself socially and politically, and of constructing an identity within a movement. These different types of applause can also be compared to the different socio-professional categories that populate the different districts of Paris and in the immediate suburbs (for those that we were able to record). Thus, the music of the applause reveals the social territory in which it is situated30. Without seeing the architecture, we hear the environment. The ear reveals to us clues on the geographical and political position of the “applauders”. In this way, certain districts are more receptive to the movements of contestation, and certain activists are going to position themselves in opposition to the conventional applause that they judge to be devoid of sense, or even completely hypocritical. But through criticism, creation and craft is manifested.

4. Hijacking a Consensual Ritual for the Benefit of Social Struggle

4.1 Hijacking the applause to make a connection: the role of sound

27In the urban environment, the #CortègeDeFenêtres described above, with the banners and the projections (for example, the unauthorized projections warning of the economic consequences of the lockdown for the culture related professions31) are themselves enough because of the numerous passersby. In rural and suburban areas, where passersby are more scarce, these demonstrations risked going unnoticed. The protesters produced visual objects that they chose to disseminate through other means of communication. They then used social networks in order to reach a wider audience. In both cases, the mobilization started on social networks and ended at the micro-local level, where it participated in recreating links with neighbours. The mobilization thus becomes a pretext for forging links on the balcony, at the window, or in the courtyards and other spaces of resocialization during confinement.

28This need to connect is especially evident among the underprivileged, the forgotten of so-called equal opportunities, and the low-income communities in peripheral France excluded from the visual public space. The latter suddenly found themselves in a position to be heard. The desire to be heard by the government became, as in traditional demonstrations, also a call for friendship and togetherness with one's peers. The songs that brought people together in social struggles, before the arrival of COVID-19, reacquired this role by expanding their audience. With the help of loudspeakers, those excluded from the visual space amplified emblematic songs from recent social struggles (see for example the official clip of the Yellow Vests of D1ST132), chanting slogans in the yards of buildings for example, far from the eyes of passersby and media cameras.

4.2 The different sound modalities of these detours: casserolade, balcony concerts for politically causes, slogans at the window, sound and light shows

29The balcony and the window, open to the public space, can thus constitute a space in between, defined here as the threshold between public and private spaces. This space was used as a banner and a place of expression to thank the caregivers. This space has also been used sometimes, through detours, to express feelings of indignation, dissent, and to collectively express a rejection of the government. We will now listen to some emblematic examples of these detours for the benefit of social and political demands:

4.3 Shouting, slogans, casserolades and DIY percussion

30Some activists opposed the applause that they considered empty of meaning, and even totally hypocritical. One could then hear an appropriation of the eight p.m. applause. People took advantage of this ritual to continue the protests. One of the sound expressions from the protests is called casserolade. These are real concerts of pots and pans, for “to clap with a pan is to protest” 33. Following the tradition of the charivari, a medieval ritual where noise was used to express a collective dissent when a social rule is broken34, the concert of pans was used to protest against King Louis Philippe in the 1830s. Thus, during the confinement in 2020, we heard again the casserolade. This sonic manifestation sometimes provided an addition to the sound environment of the eight p.m. applause.

31Let us listen to this first excerpt35. A woman at her window with a saucepan36: “Hospitals abused! Macron must pay! 37”. And another example in which we can hear “Money! Money! For the public hospital! 38”. In this last example, you can hear the rhythmic rendition of the slogan “Du fric du fric” and then people chanting “On est là, on est là…”. These are exactly the protest songs that could be heard during the street demonstrations before the lockdown; they are now organised and chanted from windows and balconies.

4.4 The sound and light shows and projections, a dynamic extension of the banners

32Other demonstrations involved sound and image. One video, for example, is an anonymous montage set to a soundtrack, found on the Facebook page Nantes Révoltée39. We can see and listen to different projections broadcast during the now traditional moment of applause at eight p.m. In the first excerpt, these words are projected onto the façade:

Money for the public hospital

It's not a war it's an epidemic, less cops more masks

Money for the public hospital

THANK YOU to the cashiers, garbage collectors, postal workers

Money for the public hospital

Money for public research

Solidarity is the weapon of the people

Let’s kill the capitalism that kills us, let's save the public services that save us

Money for the public hospital.

33One will notice here the couplet-chorus organization of the beginning, then a collection of messages that we find on the various fabric banners, and the return of the chorus “Money for the public hospital”. The second excerpt is an animated image of clapping hands against a background of pan drums. This association could be read as a paradox between the symbolism associated with the act of clapping hands – to be viewed as a continuum of the conventional applause – and politically situated pan drums. The third extract is a video of fireworks over a background soundtrack of horns, a foghorn, shouts, and applause (we will come back later to this modality of protest). The fourth extract is a video of a projection of words on a facade, the background sound being applause. We can read:

34Hospitals: Macron - Keep - Your - Tributes - We - Want - Jobs - We - Want - Beds - We - Want - Equipment - We - Want - Real - Salaries - We - Want - Real - Pensions - Neighbours - I - Love - You - Neighbours - We - Make - Noise?

35By listening to these examples, we can hear how the soundscape of the protests moved to a new environment between public and private space, creating a kind of political balconism40. The confined French cities became noisy again, as the bearers of a protest movement created a new 8:00 pm soundscape: rhythmic, noisy, and political. Unfortunately, windows and balconies were not available to everyone during the confinement. Other sound events took place outside of the window.

5. Exit the Window: The New Soundscape of Confined Towns and Suburbs in Protest

5.1 Diverting the 8:00 p.m. applause by honking horns

36During lockdown, 25 percent of the French population continued to go to work41. This segment of the population, considered essential during the crisis, could not always express themselves. Some of these workers, often on the road at eight p.m., chose to honk rather than applauding. Every evening, during the first lockdown, garbage collectors in downtown Nîmes drove and honked horns to pay tribute to healthcare workers42. Small traders, truck drivers, ambulance drivers, taxi drivers, and Uber drivers followed a similar approach43. In France, unlike other countries, these sonic expressions quickly took a political turn as medical personnel complained about the lack of government support with a plea to turn these expressions of solidarity into concrete measures to help their cause.

37Toulouse cab drivers met every week to applaud, in a sense, by honking repeatedly for the nursing staff. Their tribute was noisy, accompanied by firecrackers and loud applause, and was emblematic of their socio-professional category compared to other groups. Car horns, their “soundmark” (Schafer 1977, 10), had the effect of increasing the intensity of the demonstration, allowing for the occupation (to use protest vocabulary) of Toulouse’s place in the du Capitole soundscape44. This brings us back to the traditional practices of social movements from the second half of the twentieth and beginning of the twenty-first centuries, which focused on people’s occupation of public spaces. During lockdown, the sonic spheres of these places was expanded and magnified to poetically and symbolically circumvent the visual borders of the government decrees banning public assembly. Sound became a platform for protesters to meet and cross the bureaucratic visual borders and limitations of the lockdown. The acoustic properties of sound helped to create a link between neighbours, as it is not constrained by the physical borders of urban spaces. Contact and vision – restricted during lockdown by police controls on public spaces – lost their relevance as instruments of emancipation, leaving room for only the sonic expression of dissent.

38Another emblematic example took place when tow truck drivers from Compiegne gathered in their city in April 2020 to thank medical staff. The result of the gathering was a concert of horns and sirens superimposed upon one another45, an acoustic parade that alternated the repetitive motifs of the sirens with those of the horns, played by the drivers in a counterpoint reminiscent of the 1922 Symphony of Factory Sirens by Arseny Avraamov. This concert, so to speak, was all the more interesting in that it unfolded in the historical centre of Compiegne: the streets form sound corridors where the sirens’ mechanical and repetitive urgency mixes with frenetic applause, here in the form of horns, resulting from the drivers annoyance at the government46. As far as maritime professions are concerned, at noon on 1 May 2020, ships in commercial service in Corsica paid tribute to the sailors who keep the supply chain going with a foghorn concert, which was not heard by the vast majority of French people, nor recorded, but did in fact take place47. In the same way, in Marseille, protesters demonstrated from inside their cars in order to circumvent the ban on gatherings of more than ten people.

39The common point between all these road and sea demonstrations is that they all thanked and paid tribute to those of France’s workers deemed essential during times of crisis. Care workers, transporters, cashiers, sailors, logistics workers, and all the rest had neither the time nor the mental energy to stage protests from home. Their only instrument was the sound of their work vehicles: the car horns and the sirens. Coming from rural and suburban areas, they expressed dissent through vibratory tensions and a sonic dialogue with other working protesters who shared the same struggles. These workers, invisible in normal times, became audible during lockdown.

40This particular use of horns echoes the older “sound referendums” organized on French highways to protest the labour law reform in 2016 where car horns naturally replaced protest songs48. They also echo the more recent adage of the yellow vests, sung on provincial traffic circles: un klaxon=un soutien. Car horns can thus serve as a social and sonic marker for precarious49 or “peripheral” France50 and serve as a critique of the renewed empathy for healthcare workers only a few months after French hospital workers had taken to the streets to protest years of cutbacks across the country. Horns can then serve as a warning, not of incoming traffic, but of the various contradictory political behaviours that the government has been engaged in, often with the support of the wealthier populations who give themselves a clear conscience by applauding at eight o’clock. In comparison, these applauses are consistent with the liberal doctrine of small gestures, which now seem derisory when compared with the vastness of the disaster. Finally, through sound and through a socially conscious listening, these horns highlight a two-tier France, prompting us to consider the situation of some workers during lockdown as segregational, with a spatial separation between social classes reinforced by the confinement. It is in fact the poorest and most vulnerable elements of society who were impacted the most, both from medical and social points of view. This trend can be observed virtually everywhere in the world51.

41Horns and politically mobilized applauses position sound in dialogue with social struggles and allow us to rethink the “space of appearance”, defined by Hannah Arendt as a mere area of visibility52. Indeed, the space of appearance in which these dissident sonic expressions unfold goes well beyond traditional arenas of visibility by positioning us in relation to invisibilised workers, unrepresented citizens, and all those who are on the margins of the public sphere. Horns and applause can therefore be related to discourses of “subaltern counterpublics53”. These discursive arenas develop in parallel with official visual public spheres. They refer to the notion of “sonic sensibility54” developed by Salome Voegelin, which reorients and upsets the politics of visibility and encourages a critical reflection on government action. Through listening we are given the opportunity to uncover the hidden reality of invisibilised workers, as sensory responses encourage us to rise above the taxonomical way we understand the political. We not only listen to the sound of the car horn, we inhabit the life of the dissenting driver if we listen to the sound just for itself, departing the semantic arena of visual politics and exploring non-consensual alternative worlds.

5.2 Shedding light onto an emerging counter-space of appearance specific to COVID-19

42Politics indeed requires a space of appearance that emerges whenever people are together in their manner of speech and action. However, this space does not always exist. In contemporary Western societies, low-income communities are excluded from such a space. This means that part of the population does not appear, it does not emerge into the space of appearance. The lockdown has unsettled this situation. It has allowed the invisibilised and the weak to seize and redefine public spaces emptied by existing power. The space of appearance is no longer the exclusive domain of a powerful few. It has been deserted, and as such has been opened to the bodies of critical workers and the unemployed, invisible to the rest of society, in rural and suburban areas. Their bodies must no longer enter an inaccessible visible field to exist socially, in so far as this field remained inaccessible for everyone during the lockdown.

43The health restrictions and measures put in place during the lockdown effectively outlawed outdoor activities. The act of visual appearance, ontologically fixed and segregational, lost its purpose, leaving dissenting bodies with nothing but the dynamic and common power of the audible and the sonic55. New modalities of common interest were thus created. In this context, the traditional space of appearance shifted online onto social media through videos, videoconference calls, and virtual events, while the physical world became a counter-space of appearance where the bodies of critical workers disappeared under the weight of their repetitive work routine and neglect from the ruling classes. The clapping at eight o’clock operated to this end, as a door connecting the two spaces – between the visual world of telework submerged by screens, and the daily sonic reality, often undervalued and overlooked, of critical workers. Coming from rural and suburban areas, they expressed dissent through vibratory tensions and a sonic dialogue with other working protesters who shared the same struggles.

44Their car horns and their sirens are loud sounds56 that occupy space in the same manner that bodies would occupy a street or a square. Sound connects, includes, and overcomes visual restrictions. During the pandemic, sounds transcended the Adornian subject-object dialectic because they carry political meaning that goes beyond their physical and acoustic condition. The essence or raison d’être of these sounds is to promote social change. Finally, these sounds are instruments for the inclusion of other communities. The sounds of these manifestations of dissent, the object, and the critical workers, the subject, are part of an undertaking bigger than the sound itself and bigger than the act of perceiving sound. It refers to a common vibration, which resonates with the situation of other critical workers. As such, it sheds light on the unfair politics of the lockdown.

5.3 The particular case of Parisian suburbs

45Another group of unlikely protesters in this new counter-space of appearance is the youth living in the so-called sensitive neighbourhoods of Ile-de-France57. On 20 April 2020, an accident involving a motorcyclist and a police car in Villeneuve-la-Garenne, in the Hauts-de-Seine, led to clashes between young residents of the suburbs and the police. These conflicts, which occurred as several videos were denouncing police violence since the beginning of the lockdown, took place in Aulnay-sous-Bois, Gennevilliers, Evry, and Clichy. The soundscape of their protest is different from the sounds of the protests discussed above. Contrary to applause and horns, these improbable demonstrators were not intending to fit into a predefined social movement. Their approach was not one of thanking critical workers or expressing subaltern counterpublics’ indignation.

46The youth living in these urban neighbourhoods, who face economic and social hardships, set off fireworks and firecrackers not so much to express discontent with this situation or that government policy, but to continue living outside overcrowded apartments in social housing58. Lockdown deprived them of the little freedom that they had. For them, living outside seems like an economic, social, and existential imperative. The sound of these fireworks and firecrackers operated like sonic bombs defying visual monitoring systems. These sounds became an event in itself: the spectacle of a nocturnal struggle, which may be lost in advance, at least in a short-term perspective, but has the benefit of acting as a warning to the rest of the population about these so-called ghettoised, underprivileged, poor, sensitive, and difficult zones, which are unimaginable to the rest of the population because they are absent from dominant media representations. These youth position sound in dialogue with other forgotten struggles.

47The soundscape of these protests is not otherworldly, but it proposes alternative points of view on what the world is and how we live in it, showing what else it could be in the register of the unimaginable. Fireworks are historically featured to accompany official celebrations. Here they are endowed with a political agency of their own59. They challenge the singularity of celebration, inciting us to unsettle the real and imagine different layers of possibility. The sound of fireworks becomes an event in itself. It may be a lost battle, but it has the benefit of warning the rest of the population of an alternative future that enables these populations to escape the logic of urban (spatial and therefore visual) ethnic and economic segregation that currently prevails in the discourse on these so-called sensitive neighbourhoods. We thus enter into the register of the unimaginable, because neoliberal ideological alienation is such that an alternative seems impossible, even to imagine, which follows our earlier analysis of the invisibility of critical workers. Finally, we would like to mention the silent protest of the weakest in society, those who have no car horn to sound, no fireworks to display, and perhaps even no window or balcony from which to clap: the dispossessed, the homeless, the lonely. While observing the phenomenology of their silenced routines, ontologically there is sound, the sound they would have sounded had their concerns been heard in pre-pandemic times.

Notes

1 A first version of this article was published in Maurizio Agamennone, Daniele Palma, and Giulia Sarno (ed.), Sounds of the Pandemic: Accounts, Experiences, Investigations, Perspectives in times of Covid-19, London, Routledge, 2023, p. 50-64.

2 On 5 December alone, according to the CGT (General Confederation of Labour in France), 1,500,000 people protested in France, while the Ministry of Interior registered 806,000 protesters (Ministère de l'Intérieur 2019). CGT (Confédération Générale du Travail). 2019. “Grève du 5 décembre: réussite générale!” La CGT, December 5, 2019. https://www.cgt.fr/actualites/france/retraite/mobilisation/greve-du-5-decembre-reussite-generale.

3 Girard, Quentin. “Ami, entends-tu les chants de la protestation?” Slate.fr, October 11, 2010. http://www.slate.fr/story/28457/chansons-manifestations.

4 Coquaz, Vincent. “D’où vient l'hymne ‘On est là’ chanté dans les manifs depuis un an?”. Libération.fr, December 10, 2019. https://www.liberation.fr/checknews/2019/12/10/d-ou-vient-l-hymne-on-est-la-chante-dans-les-manifs-depuis-un-an_1768086.

5 Strikes and demonstrations have been regular and sustained since 5 December 2019 and the calendar of actions did not seem to stop. National educational staff strikes took place on 5, 10, 17 December 2019; 9, 14, 16, 24 January 2020. The strike of the SNCF (French National Railway Company) staff is considered as the longest social conflict in history in France, with 37 consecutive days between December and January. The Yellow Vests movement joined the anti-reform of pensions demonstrations on 7 December, it was then at its 56th act; the last act before the confinement, the 65th act, took place on 8 February. The movement against the PBDA had decided to stop the university and research on 5 March 2020, followed by a large number of actions and demonstrations. See https://universiteouverte.org/.

6 Berque, Augustin. 2000. Ecoumène : introduction à l'étude des milieux humains. Paris: Belin.

7 Arendt, Hannah. (1958) 1998. The Human Condition. Second edition, with an Introduction by Margaret Canovan and a Foreword be Danielle Allen. Chicago: University of Chicago Press,199.

8 Lefebvre, Henri. 2019. Éléments de rythmanalyse et autres essais sur les temporalités. Paris: Eterotopia France.

9 Nedelec, Cyril. 2016. “Le balcon comme seuil et dispositif environnemental. Architecture, aménagement de l’espace.” Mémoire de séminaire, Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Toulouse. https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01802992/document.

10 France24. 2012. “Julian Assange demande aux États-Unis de cesser ‘la chasse aux sorcières.’” France24, August 19, 2012. https://www.france24.com/fr/20120819-julian-assange-demande-etats-unis-cesser-chasse-sorcieres-contre-wikileaks-londres-equateur-ambassade.

11 Franque, Adrien. “À Toulouse, Montpellier ou Paris, la police débarque pour des banderoles anti-Macron,” Libération, May 1, 2020. https://www.liberation.fr/france/2020/05/01/a-toulouse-montpellier-ou-paris-la-police-debarque-pour-des-banderoles-anti-macron_1786871.

12 Twitter “#CortègeDeFenêtre”. Author @H_Ronac posted on the 21st of March 2020. https://twitter.com/H_Ronac/status/1241387327706013697?s=20.

13 Twitter “# CortègeDeFenêtre”. Author @AnneBonnyBonny posted on the 22nd of March 2020. https://twitter.com/AnneBonnyBonny/status/1241634984441585664.

14 The Paris Commune (“La Commune de Paris”) was a revolutionary government that seized power in in Paris from 18 March to 28 May 1871. It is considered a symbol of popular struggle and a model for communist, socialist, anarchist movements in establishing a political system based on participatory democracy.

15 Martin, Denis-Constant. 2021. “‘Le temps des cerises,’ comment analyser les rapports entre musique et politique?,” in Plus que de la musique, 167–185. Guichen: Éditions Mélanie Seteun.

16 Anonymous author. Posted on the 19th of March 2020 in Lille (France). Facebook Page “Cortège de Fenêtres”. https://www.facebook.com/Cort%C3%A8ge-de-fen%C3%AAtres-103566351286235.

17 Dupont, Marion. “’ACAB’ ou la rage anti-flics.” Le Monde.fr, May 26, 2021. https://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2021/05/26/acab-ou-la-rage-anti-flics_6081472_3232.html.

18 Twitter “#CortègeDeFenêtres”. Author @matlagratte, posted on the 23rd of March 2020. https://twitter.com/matlagratte_/status/1241801528245129218?s=20.

19 Anonymous author. Posted on the 22nd of March 2020. “Cortège de Fenêtre” Facebook page. https://www.facebook.com/Cort%C3%A8ge-de-fen%C3%AAtres-103566351286235.

20 Anonymous author. Posted on the 22nd of March 2020. “Cortège de Fenêtre” Facebook page. https://www.facebook.com/Cort%C3%A8ge-de-fen%C3%AAtres-103566351286235.

21 Renou, Aymeric. 2020. “Coronavirus : à leurs fenêtres, de plus en plus de Français applaudissent les soignants.” Le Parisien, March 19, 2020. http://www.leparisien.fr/societe/coronavirus-a-leurs-fenetres-de-plus-en-plus-de-francais-applaudissent-les-soignants-19-03-2020-8283939.php.

22 Victoroff, David. 1955. “L’applaudissement: une conduite sociale.” L’Année sociologique (1940/1948) 8:131–171. 133.

23 Ibid., 132

24 Ibid., 134

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 We could not determine the exact source (child’s toy or adult owned siren amplifier), the sound is close to the yelp siren of the “Federal Signal PA300 200 W Siren.”

28 One of the authors was able to record the applause several nights in a row and listen to the rhythms and socialization under construction in this new ecosystem particular to the confinement. A selection of the sound recordings can be listened to online: https://lemondeautre.fr/portfolio/hautes-formes-project-field-recording/.

29 “Le message du jour: faut-il applaudir à 20h?” Le répondeur de Là-bas si j'y suis, March 21, 2020. https://la-bas.org/la-bas-magazine/le-repondeur/le-message-du-jour.

30 Caenen, Yann, Claire Deconde, Danielle Jabot, Corinne Martinez, Samira Ouardi, Pierre Eloy, and Luca Jouny. 2017. “Une mosaïque sociale propre à Paris.” Insee Analyses Île-de-France 53, February 2, 2017. https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/2572750.

31 Vavasseur, Pierre. 2020. “Paris: une projection sauvage interrompue par la police.” Le Parisien.fr, October 26, 2020. https://www.leparisien.fr/paris-75/paris-une-projection-sauvage-interrompue-par-la-police-26-10-2020-8405103.php.

32 D1ST1 OFFICIAL RAP. “Gilets jaunes clip officiel D1ST1.” January 20, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ix0p5Q1937o.

33 A comment made by a user during a livestream debate hosted by Baptiste Penel on https://www.twitch.tv/usul2000. Twitch.tv. 26th of March 2020. https://www.twitch.tv/videos/576036367. (Twitch videos are automatically erased 60 days after the publication).

34 Le Goff, Jacques, and Jean-Claude Schmitt, eds. 1981. Le Charivari. Actes de la table ronde organisée à Paris (1977). Paris: Mouton.

35 All sonic illustrations are available at this address : https://soundsofthepandemic.wordpress.com/alessandro-greppi-diane-schuh/.

36 Twitter “#CortègeDeFenêtre”. Author @AGalitzine posted on the 21st of March 2020. https://twitter.com/AGalitzine/status/1241447880847773696?s=20.

37 “Hôpitaux malmenés ! C’est Macron qui doit payer” Id.

38 “Du fric ! du fric ! Pour l’hôpital public”. Author @DelsemmeClaire posted on the 20th of March 2020. https://twitter.com/DelsemmeClaire/status/1241080682727825408?s=20.

39 Nantes Révoltée. 2020. “Mieux que les applaudissements: solidaires et creatifs.” Facebook.com, March 21, 2020. https://www.facebook.com/Nantes.Revoltee/videos/638212806744206/UzpfSTEwMzU2NjM1MTI4NjIzNToxMDY3MjcyMjA5NzAxNDg/.

40 The term ‘balconism’ is born from the practice of observing the uses and practices specific to the spaces of balconies. The balcony being a space that sits in between the private and public, it participates in the public appearance of the city. It is the space of very specific practices that we can describe and analyse. Dullaart, Constant. 2014. “Balconism: A Manifesto.” Art Papers (March/April). https://www.artpapers.org/balconism/.

41 Lehut, Thibaut. 2020. “SONDAGE – Les Français et le confinement: dans le monde du travail, le coronavirus accentue les inégalités.” Francebleu.fr, April 9, 2020. https://www.francebleu.fr/infos/societe/sondage-les-francais-et-le-confinement-dans-le-monde-du-travail-le-coronavirus-accentue-les-1586355082.

42 Corger, Corentin. “EN VIDÉO Hommage au personnel soignant, les éboueurs klaxonent en centre-ville de Nîmes.” objectifgard.com, March 31 2020. https://www.objectifgard.com/2020/03/31/en-video-hommage-au-personnel-soignant-les-eboueurs-klaxonnent-en-centre-ville-de-nimes/.

43 Lanot, Clément (@ClementLamont). 2020. “Une centaine d’ambulances vient applaudir les soignants de l’hôpital de Melun qui luttent contre le #Covid_19.” Twitter, April 6, 2020.

44 Ouest France (AFP). 2020. “Toulouse. Les taxis klaxonnent une dernière fois en hommage aux soignants.” ouest-france.fr, May 12, 2020. https://www.ouest-france.fr/region-occitanie/toulouse-31000/toulouse-les-taxis-klaxonnent-une-derniere-fois-en-hommage-aux-soignants-6833296.

45 The duration of the “notes” of some sirens are sometimes held to infinity while others produce “portamentos” from low to higher registers.

46 Oise Hebdo. 2020. “Compiègne. Les dépanneurs offrent un concert de honaxons pour remercier les personnels soignants.” oisehebdo.fr, April 29, 2020. https://www.oisehebdo.fr/2020/04/29/compiegne-les-depanneurs-offrent-un-concert-de-klaxons-pour-remercier-les-personnels-soignants/.

47 Corsica Linea. “Les cornes de brume de nos navires ont retenti en hommage à nos marins, à tous les marins & professions maritimes à travers le monde.” Twitter.com, May 1, 2020. https://twitter.com/CorsicaLinea/status/1256197051110625281?s=20.

48 B.H. “Paris: les automobilistes invités à faire du bruit contre la loi El Khomri”. leparisien.fr, September 13, 2016. https://www.leparisien.fr/paris-75/paris-75020/paris-les-automobilistes-invites-a-faire-du-bruit-contre-la-loi-el-khomri-13-09-2016-6116987.php.

49 Le Monde. 2019. “Qui sont vraiment les ‘gilets jaunes’? Les résultats d’une étude sociologique.” Le Monde, January 26, 2019. https://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2019/01/26/qui-sont-vraiment-les-gilets-jaunes-les-resultats-d-une-etude-sociologique_5414831_3232.html

50 Guilluy, Christophe. 2015. La France périphérique: comment on a sacrifié les classes populaires. Paris: Flammarion. 192

51 “With a projected fall in per capita income in more than 170 countries, people without social protection will be worst hit, De Schutter said. Worldwide, about four billion people have no social protection coverage and those in precarious employment, including the 2 billion workers in the informal sector, are often the first to lose their jobs”. OHCHR (Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights). 2020. “COVID-19 Crisis Highlights Urgent Need to Transform Global Economy, Says New UN Poverty Expert,” press release, May 1, 2020. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2020/05/covid-19-crisis-highlights-urgent-need-transform-global-economy-says-new-un.

52 Arendt, Hannah. (1958) 1998. The Human Condition. Second edition, with an Introduction by Margaret Canovan and a Foreword be Danielle Allen. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 199.

53 Fraser, Nancy. 1992. “Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy.” In Habermas and the Public Sphere, edited by Craig Calhoun, 109–142. Cambridge: MIT Press. 123.

54 Voegelin, Salome. 2014. Sonic Possible Worlds: Hearing the Continuum of Sound. New York: Bloomsbury. 3.

55 Barbanti, Roberto. 2013. “Ecouter le monde”. Presented at La Semaine du Son 2013, Paris, France, January 15, 2013.

56 The horn is particularly interesting from a sonic point of view, as its sound pressure has remained that of normal times in modern cities. In Paris, for example, according to estimates released by the Paris municipality (https://www.paris.fr/pages/bruit-et-nuisances-sonores-162#le-plan-de-prevention-du-bruit-dans-l-environnement), 10 to 15% of the population is normally exposed to a value above the Lden limit of 68 dB(A). The sound of a horn, like that of sirens, is less appropriate in times of lockdown for its alerting function than for demonstrating or applauding caregivers.

57 These circumscribed territories tend to be defined as the receptacle of most of the ills of French society.

58 INSEE. 2020. “La suroccupation des logements en Ile-de-France est quatre fois plus importante qu’en province en 2017,” press release, November 19, 2020. https://www.insee.fr/fr/information/4965622.

59 LaBelle, Brandon. 2018. Sonic Agency: Sound and Emergent Forms of Resistance. London: Goldsmiths Press.

Citation

Auteur

Quelques mots à propos de : Alessandro Greppi

Quelques mots à propos de : Diane Schuh