Mahmoud Rashid Younes was only 16 when his older brother Mohamad, a school teacher, took him from their village Ar’ara to visit nearby Kibbutz Ein Shemer, in search of comrade Avraham Ben-Tzur. Ben-Tzur (formerly named Steinweg), a Jew born in Germany, immigrated to Palestine in 1938 on his own, at age 14. He joined Hashomer Hatzair, a Zionist-socialist youth movement which spearheaded Jewish settlement in pre-state Israel. He taught himself Arabic and was therefore considered “The Arab” of the Kibbutz.1 He had first met Mohamad a short while before, on mutual class trips of Arab and Jewish pupils, held in October of 1947,2 as part of a last-minute effort to maintain neighborly relationship in the area. Only a few months before the onset of the 1948 fighting, the brothers came to see Ben-Tzur with an unusual request: that teenage Mahmoud would be allowed to complete his studies in a kibbutz. At the time, the two were rejected, but Mahmoud did not forget his older brother’s initiative.

Three years later, in 1951, Mahmoud returned. With a blond forelock and Khaki pants tucked into his socks, he again sought and found Ben-Tzur, who had since moved from Ein Shemer to Kibbutz Sha’ar Ha’amakim, south-east of Haifa. “I came to continue my brother’s mission”, he said,3 declaring his belief that Arabs and Jews are not destined to eternal animosity. Again, he asked to realize his dream and be accepted to study, live and work in a kibbutz, in accordance to the settlement movement’s famed slogan: “For Zionism, socialism, and the brotherhood of nations”. This time, his wish was granted: Mahmoud became one of the first and most devoted members of an extraordinary movement which was later called the Arab Pioneer Youth.

This article will examine this unusual endeavor through the lens of a growing body of research that sees Zionism as a unique case of ongoing settler colonialism. While not negating the nationalist aspect of Zionism, it challenges the conventional perception of the Palestinian-Israeli relationship as solely a clash between two national movements, instead examining the way it is entwined in the colonial-settlement process.4 This interpretive framework echoes the concept of “entangled” or “relational” history as a prism replacing the “dual society” paradigm5 – proposing to focus on mutual influences and connections between individuals, as determined not only by nationality but also by a layered heterogeneity of factors and positions, which in turn play a role in designing practices, perceptions and historical processes.6

Hashomer Hatzair was “the mother movement” to HaKibbutz Ha’artzi, its settlement arm, and to its political arm Mapam (United Workers Party).7 Between 1951 and 19618 it invited young Arabs,9 mostly men from the country’s north, into its famed communal settlements. The Arab Pioneers – numbering more than 1,800 at the movement’s peak10 –learned Hebrew, danced the pioneer circle dance hora, raised the blue and white Israeli flag, sang the national anthem Hatikva and, in some cases, even took Hebrew names. The movement’s activities took a number of forms: one-year-long training groups, such as the one Mahmoud Younes had joined, were established in Sha’ar Ha’amkim and later in a few more kibbutzim11. A “Youth Society”, in which Arab teens lived, worked and studied for up to four years, was established in Kibbutz Yakum. There were also 20-day work camps, with as many as 14 taking place by 1956.12 Arab youth groups with weekly activities started in villages such as Ar’ara, Jish, Kfar Yasif,13 and in the cities of Acre and Nazareth. In the inaugural meeting of the movement in 1954, there were 300 participants from 15 groups set up in Arab villages. Four years later, the movement had 800 members,14 and by the summer of 1959 the number grew to 1,300 members in 52 groups. That summer, 600 members took part in 45 kibbutz work camps, and 120 members were being professionally trained in kibbutzim.15 The movement also initiated agricultural co-operatives set up in Arab villages by its alumni. Over the years, members took part in the “Shomria”, Hashomer Hatzair’s festive convention, in field trips, in Israel’s Independence Day celebrations including the famed “Four Day March” to Jerusalem, and in May 1st rallies.16 This article will focus on two of these activities, which took place on kibbutz grounds over a relatively long period of time, namely the Sha’ar Ha’amakim first training period in 1951-1952, and the Yakum youth society in 1954-1958.

Ill. 1 - Arab Pionner Youth Participating in the third “Shomria” convention in Haifa, 1956

The anomaly of this idyllic project stood out then, and still does today. The audacity it took for Mahmoud Younes to come back seeking Avraham Ben-Tzur in 1951 for the second time, three years after their first meeting, is clear when considering the life-changing events of late 1947 through 1951. The establishment of the state of Israel and the Nakba (catastrophe) of the Palestinians violently intertwined. In 1948, the Jews in Palestine were a minority of about 600,000. By the end of 1951, more than half of the nearly 1.4 million Palestinians who had lived in the area became refugees, while the new state absorbed a huge immigration wave which doubled its Jewish population. While the majority of Palestinian people was forced into exile and scattered in the West Bank and neighboring Arab countries, a minority of approximately 160,000 Arabs remained within the 1949 armistice lines, accounting for about 13 percent of its population. With about 400 villages and towns depopulated17 and nearly all the political, social and cultural urban Palestinian elite gone,18 the Arabs who remained in Israel turned into what Azmi Bishara described as “a defeated remnant of a defeated society”.19

For young Mahmoud, it was a national as well as personal calamity: his older brother Mohamad was drafted to the Arab Rescue Army and killed fighting Jewish Haganah (Zionist Military Organization) forces.20 Born to a family of landowners, Mahmoud witnessed how his village of Ar’ara lost most of its farming land.21 The villagers were subjected to a strict military rule, as were 85 to 90 percent of the Arabs in Israel – seen as a security threat, a “Fifth Column” at the heart of the fragile new state. Arab citizens of Israel had to ask for permission to study, work, leave their villages and congregate, under an ostensibly arbitrary regime of checkpoints, travel permits, curfews and confiscations. The military rule was studied by a number of scholars who often describe its mechanism as a large prison, which tightly controlled the population and effectively prevented the return of refugees and recovery of land.22 According to historian Adel Manna (born in 1947 in Majd al-Krum in the Galilee region), “Feelings of loss, confusion and helplessness combined with anger, betrayal and humiliation caused by the fierce defeat” continued to shape the lives of these survivors for years to come.23

Meanwhile, the young state of Israel was busy with its own fateful, existential struggles, and paid little attention to the remnants of its enemy. Absorbing and settling the huge immigration waves – Holocaust survivors from Europe and diaspora Jews from Muslim countries – was done using the land and resources left behind by Palestinian refugees.24 One of the few organizations of Israeli society that tried to build a bridge to the Arab minority and protest military rule was Mapam, the Workers’ Party, which HaShomer Hatzair’s youth movement was affiliated with and officially incorporated into in January of 1948. But Mapam was torn by the dissonance between its socialist, universal high ideals—manifested by the party’s attempts to include Arab members and grant Arab citizens equal rights—and between the party members nation-building zeal, which led to their active participation in the expansion of Zionist settlement.25 According to Benny Morris, as early as the summer of 1948, many Kibbutzim, among them those of HaShomer Hatzair, “pointed greedy eyes at the deserted land around them. While beginning to cultivate this land, they also settled the abandoned areas, and even fought over some of the most alluring spots”.26 Several researchers assert that Mapam was compelled to forego its notions of solidarity and moral misgivings, swept by an unprecedented post-war settlement rush27: 90 new Kibbutzim were established until 1955, among them a staggering number of 24 Kibbutzim built by HaShomer Hatzair movement alone between 1948 and 1951. The socialist settler movement continued to lead the appropriation of Palestinian assets until Israel’s total share in the land within the 1949 armistice lines increased from 8.5% at the end of the 1948 war to almost 93% in the late 1960s.28

This article is based on archival material – leaflets, reports, diaries, published memoirs and still pictures – and newspaper articles, as well as extensive interviews (some video, some audio and some phone interviews) conducted with participants in the past 12 years29. In the following sections, I will depict the mutual perceptions of Arab Pioneer Youth participants – young Arabs and Jewish founding members of Hashomer Hatzair, the latter being mostly immigrants of European descent.30 I will argue that these participants acted within a cementing grid of power relations and control mechanisms which seemed to govern every aspect of their lives. Nonetheless, I will show that within that grid, the leading members and organizers of the movement were heretical and even deviant in their own distinct communities, and that this deviance partly explains both the movement’s surprising success and its inevitable failure.

High Hopes: Sha’ar Ha’amakim, 1951-1953

Two members of Sha’ar Ha’amakim pushed forward the idea of inviting Arabs into the kibbutz: Avraham Ben-Tzur and Aharon “Aharonchik” Cohen. Cohen was a Middle Eastern scholar and head of the Arab Department at Hakibbutz HaArtzi, who was actively and radically seeking Arab-Jewish cooperation in light of Hashomer Hatzair’s 1927 pledge for “a socialist bi-national society in the land of Israel”.31 He was a controversial figure in his own kibbutz, considered as extremely left wing.32 Ben-Tzur and Cohen had to convince kibbutz members to allow the Arabs in for a trial period, to get agricultural training along with a socialist political education. Members greeted the idea with fear and suspicion, raising security concerns which, according to Ben-Tzur, were only a pretext to their mixed feelings towards the suggestion to welcome their Arab enemy, so soon after the war.33 According to Mahmoud Younes, Cohen told his fellow members: “We are educating for co-existence, and now when the test comes, we say no? If we don’t live up to our words, that would be fraudulent!”34 After heated deliberation, the principle of “Brotherhood of Nations” had the upper hand, as did Mapam party’s opposition to the military rule, seen as a tool for the rival majority party Mapai to fortify its political and economic control.35 Ben-Tzur was put in charge of assembling the group. He started seeking for suitable participants in the North of Israel, in villages in the Galilee and the “Triangle” area south of Haifa, all under military rule. There, too, he was met with fear and suspicion. “The parents and the elderly saw it as a sign of compromise with an occupying enemy, a humiliation in the face of a people who had shown no friendly sign.”36 In addition, the military rule representatives used “a propaganda of whispers and threats” to prevent young people from joining.37 Most families were religious and traditional and hesitated to send their children – particularly girls – to the expressly secular and mixed-gender kibbutz. In his detailed diary, Ben-Tzur devoted an entry to “The First Female Member” in which he lamented:

I almost despaired of this idea. Everywhere people said: Impossible, won’t happen, never. Or they promised to participate, and recoiled at the last minute. And then suddenly, agreement: Thanaa, whose parents are workers themselves. This is a revolution in the social relations. Thanaa has awareness, and she’s therefore “good material”.38

After the recruitment of two female participants for the first group in Sha’ar Ha’amakim, only a handful of women had followed – a fact that contributed to the movement’s eventual failure. Georgette Maklesh of Nazareth said, in a report about the inaugural celebration in 1954, “I’m glad to see hundreds of men here, but I’m sad that I don’t see here the Arab Young Woman”.39 The story of the Arab Pioneer Youth is mostly a male one.40

Six participants finally arrived in November 1951, and within six months, the group numbered 15, including two girls. In his diary, Ben-Tzur describes the welcome party for the group as a success, but notes that although kibbutz members were invited, none participated. He said that the members “generally fit in very well” and learned Hebrew, but most of the activity was still held in Arabic.41 An article in the weekly Ha’olam Hazeh from March 1952, titled “Radical Experiment”, had a photograph of the young Arabs wearing typical Israeli bucket caps. “It was an encounter of two alien worlds”, the article observed. “Quite a few kibbutz members had expected a gang of foul savages, while the Arab lads were anxious about their meeting with the Yahud” – Arabic for “Jew”. The report added that the sons of the fellahin (farmers) learned “efficient methods of agriculture and worked with tractors and combines, in the groves and in the apiary”.42 The kibbutz’s idea of teaching agriculture to the Palestinian farmers’ children – in some cases, working their own people’s confiscated land – continued to raise objections from the Arab older generation. Ben-Tzur was shaken by the adversity faced by his avid group member, Mahmoud Younes. In a diary entry from April 5, 1952 he reported:

Yesterday Mahmoud returned from a visit to his village. His whole family urged him to leave the kibbutz and come back to the village. “After all, you own land. It’s time you get married and manage your farmstead.” Mahmoud got into a real conflict with his family, insisting to stay in the kibbutz and promising to unite all the peasants to work together43.

Mahmoud himself described his new life in romantic terms in a letter published in 1952 in Hashomer Hatzair’s leaflet, translated into Hebrew by Ben-Tzur.44 After an Arab-Jewish outing to lake Kinneret, that included folk dancing, he wrote:

We raised the flag very slowly […] and among the hills of Mishmar Ha’emek the salutation of the Shomrim (members of the youth movement) was heard powerfully:“Hazak Ve’amatz! ” [“Be strong and brave! ”] That salutation mingled in my blood and my heart and filled me with pioneering strength.

He concluded by saying that he would soon return home to raise the banner of socialism,

a very difficult task in the backward feudal village under the rule of the military government. […] We are returning to shout out in our villages that there is a different Israel, a democratic Israel, an Israel of peace […] which is keen to connect with us in the struggle for the independence of both peoples.45

The connection loftily hailed by Younes was dotted with small misunderstandings. Ben-Tzur described the clash of cultures: “Today a new fellow came to us, from Gush Halav [Jish], named Atallah. At first, he made a very bad impression on me […] 1. Doesn’t look you in the eye; 2. Pest.”46 Atallah Mansour had an explanation for the bad impression he made. His main purpose in coming to the kibbutz was to learn Hebrew. To that end he pestered kibbutz members at every opportunity, asking what words meant. Of Ben-Tzur he said:

He was shy, but he wanted very much to be able to speak Arabic and made a supreme effort to pronounce the letters properly. We would laugh and tease him about it.47

Mansour’s village Jish didn’t have a high school. Before the 1948 war, at 14, he was sent to study in Lebanon but had to return two years later to avoid becoming a refugee.

I told myself, if I’m already in this mess, I might as well go with the flow. I had my eyes open already then. I thought this was an ideal way of life of equality and cooperation.48

To join the kibbutz he quit his job – extracting nails from planks used in construction – only to end up assigned to a construction unit on the kibbutz.

At the end of every workday I would go to the reading room and practice Hebrew. My feeling was that learning the language would make things easier for me down the road.49

Mansour and his friends learned to dance the circle dance hora. Mahmoud Younes said in a 1990 interview: “It was the first time most of us had touched a girl. We danced hora and held hands with the Jewish Girls. We couldn’t stop talking about it.”50 In turn, the Arabs taught the Jews the traditional dance debka. They enjoyed the kibbutz’s relative abundance but had to get used to porridge at breakfast and gefilte fish for lunch. “One time a nail went into my foot”, Mansour recalled.

I was taken to the clinic and told that I had to eat well, so they gave me salted fish every day. I took one taste and almost passed out – I couldn’t stand the smell.51

The workweek was 45 hours, and there were 9 hours of study. In the evenings, after work, they learned Hebrew and studied Zionism and socialism (“What’s the difference between a [Soviet] collective farm and a kibbutz? The kibbutz is a dream, the collective farm is hell.”52). There was also a short course on electricity. A young man from Arara gave a talk on the life of Pushkin and Thanaa Kopti, the young woman from Nazareth, wrote an article about the problems women faced in Arab villages. In the last issue, summing up the first year of training, Hana Basel wrote:

The Jewish kibbutz has a big influence on the Arab village. The Arab farmer, toiling with his livestock from dawn to dusk, sees the Jewish farmer working in a planned fashion, with new agricultural tools.

Sadik Dali wrote:

Our first mission is to be rid of the remnants of feudalism. Young people, get up and go to the Kibbutzim, to learn a life on which to build a future.53

In the first couple of years of the movement, Sha’ar Ha’amakim succeeded in creating an opportunity for Arabs to experience kibbutz life. However, from the very beginning, it was evident that both parties had distinct – and even conflicting – expectations. Aharon Cohen held the view that the kibbutz’s aim was to solve problems unique to the Jewish people, encouraging city youth to move to the countryside and create a model culture of an agricultural society. Arabs, on the other hand, had in his view an established tradition of agricultural labour, and therefore, what was needed for them was national liberation and social advancement.54 Ben-Tzur echoes the same approach when describing the goals he had initially set for the first training: “We thought they should return to their villages and develop co-operatives. To start their own kibbutz? That was a utopia, it was out of the question.”55 Ben-Tzur acknowledged that his protégé, Mahmoud Younes, was eager to be accepted as a member, but noted that the perception at the time was that Arabs were not ripe for kibbutz life and that Jewish members were not ready to accept them: “After all, they were very young. There were things they didn’t know.”56

Younes attested that questions were raised from the outset, by the participants themselves and also by a journalist who came to talk to the group a couple of months after the training started.

He asked us: ‘what do you think about the kibbutz? Do you want to become members? Do you want to start an Arab kibbutz’? We answered that we were excited and happy about the shared life […] they photographed us together with the Jews and it was hard to tell, who was who. This made us wonder, what’s next for us?57

For Jews, fulfilling the socialist ideals embodied in the kibbutz way of life, meant becoming kibbutz members and “redeeming” the land – land which before 1948, was mostly cultivated by Palestinians. How were the Arabs to do the same? Would they be allowed into the Kibbutzim as equal members? Or would setting up co-operatives in their native villages suffice? These troubling questions were generally left unanswered for the first couple of years of the movements’ existence.

First Breaches: Yakum 1954-1958

In 1954, the Arab Pioneer Youth Movement was formalized at an inaugural celebration in Acre, and a 14-point platform was adopted.58 Ya’akov Hazan, leader of the Mapam party, gave a sober speech, adapting the vision of the Jewish settler movement to his audience. He told the young Arabs that “you will not be worthy of the name of Pioneers if you don’t understand how to maintain contact with the Arab masses”.59 In the speech, the young Arab pioneers were told to act to unite workers worldwide and develop “the Arab village”, but were also cautioned: “You can fulfill your duty if you are faithful to the Arab people and to the cause of brotherhood with the Jewish nation, and to the ideal of co-existence.” This oxymoron was greeted with “prolonged applause”.60

A special poster was designed on which the Arab pioneer brandished two flags: the red flag of socialism but also the blue-and-white banner of Israel. The slogan chosen for the movement was “Be Strong and Faithful” (Hazak Veneman) an intentional take-off on “Be Strong and Brave” (Hazak Ve’amatz), the original Hashomer Hatzair slogan. A choir from the movement’s branch in the village of Kfar Yasif sang the Hebrew “Song of the Harvest”, and young Arabs from the village of Jedida performed Jewish and Arab folk dances along with Jewish representatives of Kibbutz Kfar Masaryk. A hint as to the motives of the Arabs to participate in this folkloristic display of socialist brotherhood could be found in another speech given at the event by Arab representative Rustum Bastuni.61 Referring to the 1948 events that cost his people their homeland, he said: “The danger of a ‘second round’ hangs over us. We must work for unity between the two nations”. Or else – he continued with what could be read as both a warning and a threat –the first victims will be “the Arab minority in Israel, the refugees on the borders and the Arabs in Jordan. We do not want a new disaster”.62

Ahmad Massarwa was 14 when Avraham Ben-Tzur came to his family’s home in Ar’ara in 1954, to recruit him for one of the most ambitious projects of the movement, the Arab Youth Society (“Hevrat Hanoar” in Hebrew). The youth societies were primarily intended for Jews who emigrated from Muslim countries, as well as holocaust survivors and other children whose parents couldn’t care for. The children lived, worked and studied in the kibbutz between ages 12 to 18, and were expected to fully assimilate in its social fabric.63 Kibbutz Yakum, founded in 1947, started hosting groups of young Arabs only six years later, in 1953. Ahmad attests his family couldn’t fully understand, let alone refuse, the offer to send him away.

My parents didn’t know what a kibbutz was, it was all in a fog for them. The only Jews we knew were soldiers. There was hunger and chaos in the village, they had nothing to give me. There was no wheat for bread, only sorghum flour, and if we went to buy bread in the city we were fined by the military police. Farming land was confiscated so my father worked as a janitor. I was one of the best students in my class, but there was no high school in the village. From our conservative, religious village, I was invited into an ideal, hidden world. The kibbutz had food, electricity, a shower with running water, a bed with linen, girls wearing short pants. It was all new and fascinating.64

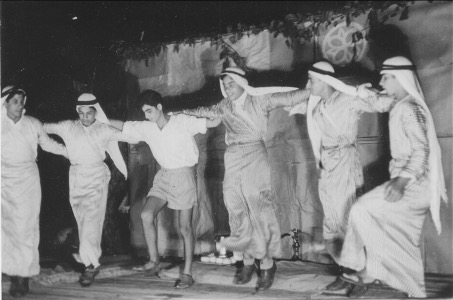

Arab Pioneer Youth in the Yakum youth society, dancing debka, 1955

Copyright: Yad Yaari Research and Documentation Center

Ill. 2 - Arab teenagers dancing.

When Ahmad arrived to Yakum he was greeted by his counselor, Haim’ke (nickname for Haim), who immediately gave him a new, Hebrew name: Zvi. He joined Nitzanim (Hebrew for “buds”), a group of 15 Arab boys, who were all given new Hebrew names such as Yehuda, Yoram, Amos and Nathan. The boys worked in agriculture and received professional training (Ahmad learned carpentry and accidentally sawed off one of his fingers). The group stayed in the kibbutz illegally, without permits. Ahmad vividly remembers the incident when military rule police came to Yakum’s gate, demanding the Arabs be handed over. While the Arab group members hid behind their living quarters, kibbutz member Shaul Yaffe, a 1948 war hero, rushed with other Palmach65 veterans to confront the policemen and greeted them with contemptuous defiance. One of the policemen shot in the air as a warning, but the kibbutzniks briskly drove them away.66 Young Ahmad felt a sense of relief, security and belonging.

He was especially enamored by his new life as a communal farmer:

When I went to plow the fields, I didn’t even return for lunch. I was connected to the kibbutz through working the land, seeding and plowing. I felt it was mine.67

His ties to the kibbutz strengthened as he was taught Hebrew and socialism, reciting the Ten Commandments of Hashomer Hatzair, starting with “Hashomer (member, literally Guard) is a man of truth”, and “Hashomer is the pioneer of revival for his people, his language and his homeland”.

By and large, Ahmad – who lived in Yakum until age 18, between 1954 and 1958 –started noting there were class differences even in the socialist kibbutz.

We, the Arab Youth Society, were the same age as the Jewish ones, but they worked three hours and studied five, and we worked five and studied three.68 So I started to ask: why? I was told that ‘Youth Immigration’ (‘Aliyat Ha’noar’, a movement funded in 1934 to facilitate the immigration of children to Israel) was funding the Jews. I found it hard to believe that the national Kibbutz movement, with all its strength and ideology, might financially collapse if it supported our group of 15 boys.69

Similar doubts were voiced by Walid Sadik from Tayibe, who lived and worked in Kibbutz Gan Shmuel during his vacations as a university student, starting 1955. At first, he was happy to quit his job shuffling rocks for construction and receive protection from the stifling military rule, but he soon started to feel the members ignored him and treated him as a foreign worker. Moshe Burian, who replaced Avraham Ben-Tzur as the movement’s coordinator, lamented in a 1956 report to the Arab Department at Hakibbutz Ha’artzi that “some kibbutzim didn’t treat the work camps seriously enough and didn’t take proper care of the boys”, and that this undermined the core idea of the brotherhood of nations. Burian mentioned that due to the harsh conditions in the Arab villages, many were motivated to participate in order to be paid the meager daily salary, and warned that work camps might become “hired labor in disguise”.70

Some members of the Arab Pioneer Youth Movement had indeed started to feel a sharp dissonance regarding not only their equal standing in the everyday life of the kibbutz, but also the basic power relations between them and the Jewish settlers who hosted them. They knew full well that many kibbutzim were partly built on Palestinian land, and that a few of the very same members protecting them from military rule had played an active role in taking over the land just a few years before. Sadik wrote:

I always attempted not to bring up the confiscated land issue in the kibbutz, but the painful reality pushed me to ask questions.

Gan Shmuel was partially built on the land of Hirbet As Sarkas, and Sadik personally knew the people who had deported the villagers in 1948.

I knew them by name and by face. They were military commanders who actively followed government orders meant to oppress and disinherit the Arabs.71

Areej Sabbagh-Khoury described how Hashomer Hatzair Kibbutzim chose to “forget” how they took over Palestinian land, while at the same time “remembering” and even commemorating the physical existence of the villages and their people. Common modes of remembering were overstating the barren primitive state of the Palestinian villages, as opposed to the modernity of the kibbutz, and highlighting the good relations between Jewish kibbutzniks and their Arab neighbors before the war.72 Both modes are evident in Ahmad Massarwa’s account:

People in the kibbutz always said that their relationship with the Arabs was very good, that they supplied the Jews with milk and eggs and that they were great neighbors. Then, one day I was told: Zvi, take the tractor, go to the Arab house and bring the crates. I went, and discovered a villa, a palace, with a well, a citrus orchard, with land all around, and no people. Where were they? I was told they had left in 1948. Then I asked myself: how come they left? If they really had such wonderful neighbors, what made them leave? And why didn’t the kibbutzniks stop them in the name of the brotherhood of nations? I couldn’t imagine anyone leaving their home, their land and their livestock, and willingly becoming refugees. I used to go to the abandoned and ruined Palestinian homes when I wanted to be alone, and wonder about it. At roll call, I went on singing Hatikva (Israel’s national anthem) with everyone, but questions started to come up that had no answers.73

According to Ahmad, his counselor used to reprimand him for bringing up those “very grave questions”.74 But mostly, the Arabs, wishing to assimilate, were hesitant about confronting their benefactors in the kibbutz with the loaded issue of land. “We were still under military rule, under supervision and suppression, our mouths shut and our feelings bottled up, and we ignored all of that consciously so that we could enjoy the pleasures of the kibbutzim”, Walid Sadik said.

When we did occasionally raise the issue that the kibbutzim, which declared that they were against land expropriations, were in fact settling those same expropriated lands, we were told: “When peace comes we will get along. After all, to this day not one refugee has shown up to demand his land.”75 We didn’t have a Palestinian consciousness such as exists today, we talked about the “stolen land”, not about Palestine.76

According to Sadik, at the time, pragmatism prevailed: “We were interested in a salary, because there was no money in the village then. The payment we received for our work was good and more important at the time than those embarrassing questions.”77

Shattered Dreams: The Final Years

Between 1959 and 1960, Arab Pioneer Youth was at its peak, with about 1,800 male participants in local youth movement branches and in short-term work camps. The work camps supplied needed working hands for the kibbutz, but they did not give sufficient professional training to the young Arabs.78 After a two-month work camp in Kibbutz Sa’ar in 1960, member Arsalan Sabah summed up his experience:

Obviously, the kibbutz is a good thing [but] after the work camp ended, we started to feel how the life in our village was empty and barren. We saw in the kibbutz the good social relationship and the communal spirit, compared to the village […]. our future isn’t pink.79

Sabah stated that the chances of his generation to advance professionally were limited, as they must stay in the village, bound by military rule, and provide for their families. “It seems that only if we are allowed to graze that fresh spring grass – learn a trade – there will be a solution to our present agony and feeling of dead end.”80 Work camps were canceled in 1961 because they were no longer seen as giving ideological training, but merely as a source for hired working hands for the kibbutz. They were later renewed until they were canceled again, while some activities went on until 1965.81

A few cooperatives set up by movement members in Arab villages had modest success. In 1956, a cooperative vegetable garden called “The Pioneer” was founded in Kafr Yasif. In Taibeh, an agricultural cooperative called “The Hope” was established and included a plan – never realized – to set up a movie theater. The most successful cooperative was a water-drilling project that Younes established in Arara in 1957. But the dearth of land, funding and support from the state establishments, along with the lack of participation of the local Arab villagers, doomed most of the cooperatives.82 The end of the military rule in 1966 created possibilities for study and employment for the suddenly mobile young Arabs. Thousands flocked to the cities to work in construction. The Arab Pioneer Youth movement no longer existed, and its groups were dismantled.83

The movement’s demise is best explained from the dual perspective of its participants. Explanations given by Jewish movement leaders offer a somewhat contradictory mixture of ideological and practical considerations, a mixture typical to Hashomer Hatzair as a whole.84 Protocols of discussions held by kibbutz leaders attest that they believed the movement ended due to lack of leadership among the young Arabs, lack of independent socialist political activity, and the shift of educated youth to the cities towards the end of the military rule, when its restrictions were eased.85 Raz and Netzer, in their 1976 study, state that the movement was not “an authentic grassroots movement” and quote Arab Pioneer Youth member Razi Sa’adi who said: “There was always a Jew above us to run things […] we were never allowed to be independent, as if we are not mature enough to lead the movement.”86 Raz and Netzer point to what they see as a gap between the socialist ideology of the Jewish founders and “the mentality of the followers, whose first and foremost motive was avoiding the restrictions of the military rule”.87 Avraham Ben-Tzur observed that “The Arabs are not fit for this lifestyle”,88 noting in his diary that “certain a-social traits are deeply engrained in this youth […] it will be a long time till we uproot their feudal habits and teach them a communal lifestyle”.89 According to Ben-Tzur, the end was also hastened by the volunteers from abroad who streamed into the kibbutzim starting in the early 1960s. “Culturally, they were far more suited to kibbutz life, so there was no longer a need for Arab working hands.”90

Interviews and written records by a number of Arab members point to two main issues that – from their perspective – were decisive in shattering their kibbutz dream. First was their ambition to become kibbutz members or establish an Arab kibbutz. The long-term relationship with Hashomer Hatzair, starting from an early age, of members such as Mahmoud Younes, Ahmad Massarwa and Attalah Mansour, led them to believe this ambition was realistic, although Hashomer Hatzair never formally proposed that Arabs become full members or establish new settlements. In 1957, Ahmad Masarwa tried to obtain agreement for establishing an Arab kibbutz in northern Israel, close to his native village of Ar’rara. He went to talk to Mordechai Bentov, Mapam member who was Minister of Development. Bentov sent him to Re’uven Aloni of Israel’s Land Administration. Aloni asked that Ahmad bring a detailed list of participants, including women, and provide various documents. Ahmed attested that after a year of going back and forth, Aloni finally told him: “Ahmad, don’t be naive. On the expropriated land of your village we will establish three Jewish settlements, which will take up arms when needed.”91 A year later, Younes asked Agriculture Minister Kadish Luz to set aside land to build an Arab kibbutz. According to Younes, “his answer was evasive. He wrote us that the Jewish Agency was in charge of settlements, not the state”.92 Younes said that although his family only had about 70 dunams of land left from 247 they had before the war, he was still naive enough to believe the government may agree to start a kibbutz in order to improve relations between the peoples, and give the Arabs land rather than take it93.

The second issue was the fate of mixed couples. As a result of the movement, a few love stories between young Arab men and Jewish kibbutz women came into being. None of the couples stayed in the kibbutzim. One couple moved to Tel Aviv and started a family there. In another case, the woman converted to Islam and the couple raised their children in the Arab community of the husband’s hometown. One love story became a high-profile struggle, waged by Tzvia and Rashed Massarwa. Rashed had joined an Arab Pioneer Youth work camp when he was a boy in 5th grade, and continued to live in Kibbutzim. After he fell in love with Tzvia, the young couple was pushed out of her native kibbutz.94 They married and had a son, and were then rejected by another kibbutz – Gan Shmuel – after a heated debate between its members. “Is the kibbutz racist?”, the dramatic headline of a 1964 article in Ha’olam Hazeh about the couple’s ordeal, set the tone for extensive media coverage of the juicy story.95 The participants of the Arab Pioneer Youth were deeply shaken by the fate of Rashed and Tzvia, and some saw it as final proof that continuing the kibbutz life wasn’t a possibility for them.96

In the aftermath of the movement, many former members remained social and political activists. The vast majority joined Mapam and helped the party recruit voters among Israel’s Arab citizens. Mahmoud Younes was paid to work as a Mapam party secretary, and was jokingly nicknamed in his village “Ya’ari of the Arabs”, after Jewish socialist leader Meir Ya’ari.97 The movement produced leaders in the municipal level and even two Parliament members: Walid Sadik and Mohamad Watad. Sadik was also a vice minister of Agriculture in Yitzhak Rabin’s 1992 government. Atallah Mansour became the first Arab journalist to write in Hebrew, as a correspondent for Ha’aretz newspaper for more than three decades. He is also the author of the first novel written in Hebrew by an Arab citizen of Israel, titled In a New Light, about a young Arab who falls in love with a Jewish woman and is allowed to remain in the kibbutz only at the price of posing as a Jew.98 Ahamd Masarwa spent four years as member of the Arab Pioneer Youth in Yakum and another couple of years as a hired worker in Kibbutz Ga’ash before returning to his village. As there was no employment there, he became a construction worker in Tel Aviv. After the 1967 Six-Day War, he joined Matzpen, a radical Jewish-Arab political group, and was active in Jewish left-wing circles.99

The two central Jewish architects of the Arab Pioneer youth, Avraham Ben-Tzur and Aharon Cohen, both became peripheral figures in the kibbutz movement. Ben-Tzur wrote articles and books about the Arab world, and later devoted himself to painting. Cohen became an academic after serving a prison sentence on the charge of spying for the Soviet Union. Another Jewish participant, Yossi Amitay, was born and raised to a middle-class Tel Aviv family. His decision to learn Arabic in high school changed the course of his life. He joined Hashomer Hatzair as a teenager, and became the coordinator for the Arab Pioneer Youth between 1959 and 1961. He described Aharon Cohen as an outstanding and unique figure because of his ability to “walk on top of the wall and see both sides, both the Jews and the Arabs”.100 Amitay, who became a kibbutz member, sees himself as Cohen’s follower. He recalls his own participation in the 1964 military Four Day March to Jerusalem as the movement’s counselor, the only Jew marching with a group of Arab Pioneer youth, like them wearing a traditional kafia and akal. His photograph, peeking out of a tent during that march, under a sign bearing the movement’s name in Arabic and Hebrew, seems to capture him as an outsider, someone who had deviated from his own society – as did most of those involved in the Arab Pioneer Youth movement.

Conclusion

The Arab Pioneer Youth movement served the urgent needs of its participants in the first few years of the state. For the Arabs, subjected to a strict military rule, it was a chance to study, work, simply survive. It was also one of the only ways they could attempt to assimilate socially and culturally in the new state that was established in – and largely on the expense of – their homeland. For the Jewish kibbutz members, the initiative offered a chance to demonstrate ideological fulfillment of ideals, at an early statehood period that put most of these ideals on hold in favor of fervent construction of settlements along with political compromises.

The Jewish founders, as well as the prominent Arab members of the movement, were devoted idealistic activists, who possessed genuine curiosity and zealous ambition. They stood out in their own communities – and their own communities eventually discouraged them in different ways from continuing this unusual experiment.

Historian Shaul Paz, who grew up in Kibbutz Mizra, asserts that the Arab Pioneer Youth was the sort of utopian challenge that Hashomer Hatzair, as a youth movement, needed “in order to fire up the young people and get them to cooperate. They had to rally around a lofty idea”.101 Hashomer Hatzair was described by journalist Uri Avneri as having had two souls: “One commanded: Settle! Conquer the land!... the other called for brotherhood of nations, for national and international justice.” According to Avneri, the Jewish socialist settlement movement attempted to ease its tormenting existential conflict by creating an imaginary beautiful and just world, which was very different from reality.102 In the broader sense, the Arab Pioneer Youth served the needs of Hashomer Hatzair to keep defining itself as an ideological opposition during the first years of the state, without paying a major price for rebelling against mainstream Israeli society.

The invitation to enjoy justice and equality in a new ideal society, ostensibly extended from the Jews to the Arabs via the Arab Pioneer Youth movement, was historically and politically conditioned, and it expired as soon as the conditions changed. Arabs were seen as guests in their own homeland, and were never really welcome to assume positions of power or to share land and resources. Atallah Mansour offered the following image to describe the dynamics between Hashomer Hatzair and the native-born Arabs:

They came to us, to our house, and said: We want half the house. After that they said, fine, you can stay. If you help us wash the dishes, maybe we’ll give you a room. But if I stay in my own house, I want to sit in the living room, not to live in the yard or in the hallway, where the shoes are kept. We were equal in principle, but we weren’t treated as equals for even one day.103

Paradoxically, the more the Arabs succeeded in realizing their socialist ideological training, naturally wishing to become full kibbutz members or start their own kibbutz, the more they were disappointed and marginalized. The Arab Pioneer Youth left a bitter-sweet legacy of shattered dreams. It is a poignant example of the way power relations between the winning majority and the defeated minority living together in Israel played out during the state’s early period – and to the way these power relations continue to play out today.