Music and Globalization: Diversity, Banalization and Culturalization

Alexandre LunsquiDOI : https://dx.doi.org/10.56698/filigrane.161

Résumés

Abstract

This article analyses the roots of globalisation, its political, social, and economical developments, and how the phenomenon has affected music produced today. Geared toward consumerism and economical expansion, most of the societies in today’s world are on a collision course with cultural values of a less materialistic nature. Some questions arising from the analysis: Is it possible to go beyond mere flirtation with other cultures around the world – especially the ‘exotic’ ones – to pursue a balanced and enriching cross-fertilization among these cultures? How can music escape the purely market-oriented goals of today’s corporately controlled globalisation, if artists themselves become the paradigms of cultural banality? The article also shows the use of an African-Brazilian instrument, the berimbau, in contemporary music as a form of in-depth research and exchange among different creative practices.

Texte intégral

Introduction

1First, the facts: Globalization seeks to enhance economical growth by stimulating trade among nations. The process does not prioritize cultural diversity and departs from a clear and simple premise: we are all consumers. The results of this phenomenon are contentious and suggest that governments and institutions around the world should re-evaluate transnational trade procedures in the name of sustainable development, peaceful coexistence and preservation of culture. Music, being one of most important manifestations of human culture, is intrinsically connected to globalization both positively and negatively. In this article, I will analyze the impact of globalization in music primarily by questioning anthropological habits that have crossed centuries and shaped our world economically, socially, and culturally. Also, I will examine the role of the music industry as well as the artist’s responsibility in the process. Further in the analysis, I will describe my own experiences composing contemporary music for an Afro-Brazilian instrument – the berimbau – as an example of cultural pluralism transcending geographic and aesthetic barriers.

Anomalies of a Journey: Interaction and Culture

2Throughout human history, survival, differentiation, power and knowledge have formed a quadrant that has responded for to luminous and spectacular actions, as well as evil and tragic ones. As we analyze how social and geo-political developments have forged the world up to the present day, we observe that a balanced system without predominance of one group over another – by using physical, ideological and/or economical violence – has never existed. We have come to realize that interaction, which is in the core of our human condition, also presents a threat. During this process, local, regional and global realities have collided and overlapped resulting in a complex, multi-cultural, and ever-changing web of territories that challenge our understanding of Nation.

3In a reference to three representative nineteenth-century Afro-Brazilian writers who were criticized for being internationalists1 Decio Pignatare points out the artificiality and incongruence behind the idea of nationality: “How is it possible for they not be internationalists if their ancestors were forced out of their own land, taken as slaves and tortured by the Luso-Brazilians ?”2 The decimation of indigenous populations in both North and South America – the only local human inhabitants of these places – is another example of the artificialities behind the idea of national legitimacy. Unsolicited visitors become hosts and vice-versa : a long process has shaped the world like a bulldozer shapes a backyard.

4With different levels of diplomacy, and propelled by high technology and contemporary mercantilism, almost all human activities are now related – voluntarily or not – to the process of globalization. If the term suggests any association with unification, it soon becomes clear that it is less about embracing the world as a community than expanding markets to the highest possible levels. The global community is, in fact, a rigid three-part stratum constituted by dominant, semi-peripheral and peripheral countries whose relationships are dictated by the market rules. In such a pragmatic system, cultural integration and integrity seem to have little importance if compared with efficiency and profit. The system works for many people, though, especially considering how easily we tend to forget some of the most important developments of our history, e.g., colonialism. Furthermore, social exclusion is often treated simply as a byproduct of the mechanism; a malfunction of the machine. However, if almost half of the world’s population struggles to survive on a dollar a day, the idea of economic prosperity leading to social prosperity – which is the main motto for supporters of globalization – needs to be revised.

5The impact of globalization on the arts is also kaleidoscopic. Particularly in music, it has led to multi-cultural endeavors with very distinct nature. If on the one hand it has allowed for a fertile exchange of knowledge and creative practices among artists worldwide, on the other its commercial rhetoric has contributed to the vulgarization of many kinds of music by distorting its cultural values and replacing them with purely commercial goals. It is, therefore, amidst anxious and celebratory narratives3 that, among other things, I believe it is necessary to protect music from music itself. Let me explain: If music becomes a commodity to serve the entertainment industry, then it is more than time to protect music genres that were not meant to serve corporate economic agendas or superficial fantasies of hypnotized audiences – and artists – who usually endorse – or simply do not care about – this process of cultural banalization.

6Article 1 of UNESCO’s Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity states :

“As a source of exchange, innovation and creativity, cultural diversity is as necessary for human kind as biodiversity is for nature. In this sense, it is the common heritage of humanity and should be recognized and affirmed for the benefit of present and future generations”4.

7The dangerous paradox in this statement is that concepts like exchange, innovation, and creativity can be used either to support the status quo, or to defend cultural diversity, as claimed by UNESCO. A central point in this discussion is that what is necessary for human kind can receive very different interpretations depending on whether the question is being formulated by the industry or by those urging that life is more than consumerism. One thing is certain : When everything is for sale, culture can be treated simply as another potential revenue source. From the production of music to its perception, from how we understand and respect the traditions of this art to the exploration of new sound territories and the exercise of independent creativity and free-thinking, market-oriented priorities of corporate globalization have crucial – and frequently negative – consequences in the music-making process.

Culture versus Corporation: Music as a Product

8With the culture of market values spreading out throughout the world, television, disposable music and a wide array of alienating products have gradually replaced local cultural values. The ethnomusicologist Steven Feld asserts :

“The hero and villain of this situation, the music industry, has triumphed through continuous vertical and horizontal merger and consolidation. By aligning technologies of recording and reproduction with the dissemination capacities of other entertainment and publication media, the industry has accomplished the key capitalist goal of unending marketplace expansion”5.

9Today, a frustrating and paradoxical reality is taking place especially among poor families from peripheral countries. In many cases, these are communities that have lost any hope of ascending in the stratification pyramid. Their local culture has become completely vulnerable to any external and often dominant influence. Through the penetration of television worldwide, these families whose children barely have access to education are constantly exposed to ludicrous merchandizing and all sorts of superfluous goods only accessible to wealthier parts of the society – themselves the pillars of lavish consumerism. The power of mass media is ubiquitous and could be a valuable tool if at least partially utilized for educational purposes. However, it is well known that with education come social awareness, cultural consciousness, and critical judgment, which are forbidden resources to populations controlled by all kinds of economical, social and political oppressive matrixes.

10Following the same motto, it is interesting to observe how music becomes quite volatile in the industry’s hands. For example, what today can represent an anti-establishment cultural manifestation in a particular community (e.g. hip hop), tomorrow can be easily transformed into a stereotyped and marketable product for global consumption that carries little or nothing from its original ideologies. One observes a severe degradation of anthropological values taking place when the market controls and distorts the cultural identity of a community. Unfortunately, developments of this kind can be often found in the musical genre known as world music, agenre that has attracted a growing audience in the last few decades6. I would like to reproduce here Steven Feld’s disturbing account of the itinerary of an African lullaby originally recorded for a project for UNESCO in 1973. The song was later remixed and included in a very popular CD:

“The recording [named Deep Forest] has attracted a huge audience worldwide, selling approximately four million copies and appearing in several editions and remixes. Several songs, including ‘Sweet Lullaby’ appeared in video form ; several, again including ‘Sweet Lullaby’, were also licensed as background music for TV commercials by, among others, Neutrogena, Coca-Cola, Porsche, Sony, and The Body Shop”7.

11In addition to the distortion of the original cultural value of the song, no compensation was given to the Baegu community – where the original music came from – since this music is placed under the category of oral tradition, and therefore receives no ownership protection.

“Academically that means that her song typically circulates in an aural and oral economy, without an underlying written or notated form. Legally, however, the term oral tradition can easily be manipulated, from signifying that which is vocally communal to signifying that which belongs to no one in particular. When that happens, the notion of oral tradition can mask both the existence of local canons of ownership and the existence of local consequences for taking without asking”8.

12The late Milton Santos, a Brazilian geographer and thinker, himself a descendent of slaves, stated: The essence can be found at the local level, and the appearance at the global level9. These notions cannot be treated retroactively only. On the contrary, the essence is an a priori condition and cannot be overlooked by the propellers of globalization. The central spine of the problem is that smaller ethnicities, especially from peripheral countries, are often mistakenly treated as being inferior and naïve, as well as culturally monolithic and immutable, and ready to be assimilated by more powerful cultures. One overlooks the fact that, in spite of their already mentioned social vulnerabilities, these populations still carry deep cultural values and often have superior environmental awareness, virtues that are becoming irrelevant in today’s insatiable race for economic expansion.

13To illustrate this discussion, I would like to briefly examine two rich musical manifestations coming from completely different contexts. One has survived atrocities, resisted foreign domination, and is a paradigm of human creativity and communal celebration. The other is the result of centuries of aesthetic and technological transformations that have led music creation to conquer new territories of artistic expression. I am referring to the complex polyphonies of the pygmies Aka from the Central African Republic and the investigative nature of Western contemporary classical music. Considering our way of making music, i.e., as part of a larger context that depends upon solid institutions, would the achievements of the latter be possible without centuries of globalization? While the answer to this question goes beyond the scope of this article, I would like to point out that, if there is something to be learned – and I hope there is it –, is that both of these artistic expressions are linked not by political forces or historical events, and much less by commercial interests or institutional needs, but rather by their transcendent values10 and profoundness. I wonder if we can transpose this perception to other areas of the society instead of simply considering it as an abstract notion. We would be speaking here of a different kind of globalization, one primarily based on mutual respect and understanding.

Music and Integrity: Research and Exchange

14Recently, UNESCO increased the number of members of the Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage to more than 50 countries. Under this program, UNESCO tries to preserve Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by first mapping out cultural manifestations according to Risk of Disappearance and then elaborating an Action Plan. Among the cultures that can benefit from such a program are the Aka pygmies from the Central African Republic, the Yoruba-nago from Benin, the Wajapi Indians from northern Brazil, the Zappara people between the Peruvian and Ecuador Amazon, the classical music from Iraq known as Maqam, the Mongolia’s nomad culture known as Morin khuur, the Vietnamese Nhac nhac music, and a few dozen other cultures around the world that have been gradually put on the verge of disappearance. Specifically in relation to music, UNESCO states :

“The function of music and its tool – the instrument – must not be limited to the mere production of sounds. Traditional music and instruments convey the deepest cultural, spiritual and aesthetic values of civilization, transmitting knowledge in many spheres”11.

15In contemporary classical music, the exchange among composers coming from different regions of the planet has never been so strong. At this level of artistic exchange, one hopes that cross-fertilization is not a mere superficial collage of styles and even less an amalgamation of disparate cultures being linked through artistic tourism. Rather, it is about “a voyage of discovery, a sonic experience of contact, an auditory deflowering that penetrates the harmony of difference”12. This means that, from the creative side, artists should be free to manipulate and transform sound phenomena and everything they might represent without barriers. From a social perspective, however, a solid commitment to guaranteeing a healthy exchange of intellectual, cultural, and educational benefits must exist that goes far beyond commercial interests.

16For the past six years in collaboration with American percussionist Greg Beyer, I have been working on a series of pieces involving the Afro-Brazilian instrument known as berimbau. The instrument

“is part of a family of ancient instruments known as musical bows. The instrument is a representative from Brazil with African roots. Its closest relatives come from a region of southwest Africa currently occupied by the country of Angola… The literature mentions depictions in cave paintings from 15,000 BC. The berimbau is made of a long hardwood or bamboo staff of various sizes. Running from end to end of this stave is a stretched string, fastened with tension to the stave in various manners. The material of the string can be of natural materials (e.g. twisted animal hide or hair), or of steel or some other metal wire”13.

17Also, a gourd is attached to the stave in order to provide resonance. In terms of performance techniques, one hand holds the instrument and a large coin or flat stone, and the other holds a small stick that is used to strike the string. An external percussion instrument called caxixi adds a kind of white-noise accompaniment to the sounds of the instrument.

18My personal approach to the berimbau was to research new technical possibilities, incorporating a new music language while tackling the deep historical elements that are intrinsic to the instrument. To date, I have written a rather complex piece for solo berimbau, entitled Iris (2002), a piece for six berimbaus entitled Repercussio (2005), and a piece for nine instruments and berimbau called p-Orbital (2005-06). This new orientation of the instrument by no means represents a denial of its own traditions. I stated my belief in Greg Beyer’s doctoral dissertation :

“Proposing new ways of playing the berimbau is a form of thoroughly investigating some of the historical and technical aspects related to the instrument. I wanted to create something that would incorporate the historical complexities surrounding the instrument and its traditional language chafing against a rhetoric that invokes microscopic explorations of timbres, kinetics and form. By doing so, I was being faithful to my musical beliefs as a contemporary music composer as well as to the complex social and cultural gestalt that accompanies this instrument.

The idea of freedom and/or the lack of it was also essential to the construction of the piece. That is why, in first place, I created a solid structural frame that suggests imprisonment and rigidity. Paradoxically, more vaporous material is used in these rigid sections. The conflict between the strict frame and the actual sound suggests two things : the contradiction between history and reality – the lies associated to the idea of slavery abolition in Brazil – and the complementarity between mind and body. For example, the upward gestures going beyond the wire or the wood of the instrument are always trying to escape some kind of behavioral predictability. These gestures want to escape the physical frame of the instrument. I think that, at least in the context of this piece, the mind is directly associated to the idea of freedom and never to the idea of conformity. One cannot forget that the slaves, while being kept captives for centuries, never gave up resisting. Finally, for me the notion of giving new perspectives to something is directly related to the awareness of it”14.

19To some extent the level of idealism expressed in such statements is not very different from the idealism of making contemporary music in third-world countries. The first two examples below are from the score of Iris, for berimbau solo. Other than the conceptual ideas surrounding the history of the instrument, I tried to generate a wide spectrum of sonic elements based on the struggle between the technical limitations of the instrument (ergonomic constraints), a more microscopic orientation to timbre and the use (or denial) of rhythmic matrixes commonly associated to the instrument. It is important to point out that the berimbau does not have a melodic nature. On the contrary, usually the pitch collection is limited to two or three pitches that outline the rhythmic patterns of capoeira15 playing. In Iris, however, I wanted to expand the pitch possibilities to an extreme, mapping the wire as if I were dealing with a string instrument. Instead of melodies, I used small contours that are controlled either by very precise intervals (quarter-tones) or generic shapes (ascending and descending). Among the new techniques created by Greg Beyer and largely explored in this piece is the use of a harness that allows the performer to free both hands while playing the instrument. The opening of the piece is based solely on sounds coming from the scratching and striking of the gourd with two sticks. The technique allowed me to explore complex noise envelopes that resulted in textural counterpoints. This attitude of dissecting an instrument and re-creating its sonic possibilities is very much analogous to the instrumental investigation that a composer like Helmut Lachenmann and others have done with western instruments. It is a constant dialogue between the new and the tradition in the hope of transcending both spheres to create a new reality. In example 1, three layers of material happen simultaneously: The right hand dialogues between percussive attacks directly on the wood and melodic contours with regular and irregular speeds. Meanwhile, the left hand creates a polyrhythmic counterpart by striking the open wire with the large coin.

Example 1. Alexandre Lunsqui’s IRIS (2002).

20The example 2 makes use of glissandi of various kinds, another technique that is unusual for the instrument. Greg Beyer pointed out that these figures reminded him of “Xenakis’ musical experiments in imitation of the chaotic movement of gas molecules, each with its own glissando of an individual, specified length”16. This exemplifies the microscopic way I was approaching the berimbau.

Example 2. Alexandre Lunsqui’s IRIS.

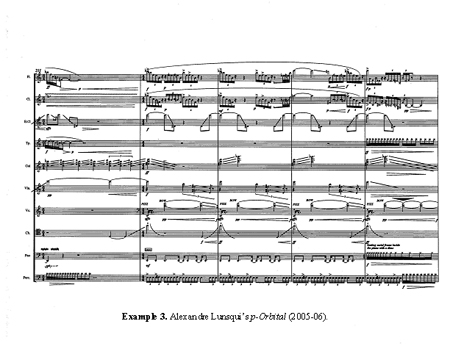

In another work, entitled p-Orbital, the berimbau (example 3, the last instrument on the score) is part of an ensemble with nine other instruments (flute, two bass clarinets, trumpet, electric guitar, piano, violin, cello, bass). The piece explores a wide array of elements varying from textural material to spectral harmonies, from raw sounds coming out of bottles of water and sand paper to driving rhythmic elements. To some extent, the techniques used for the berimbau in this piece follow the traditions of the instrument. However, here the berimbau is used to generate noise, varying from harmonic and to inharmonic sounds, which functions as a link between the various kinds of materials used in the piece. Noise elements resulting from frictional and percussive articulation, harmonic entities, and rhythmic flow, the berimbau underlies the grammar while controlling the musical syntax throughout the piece. Consciously avoiding the traps of simplistic stereotyping while being reinforced by the orchestral instruments, the sounds of the berimbau are completely re-contextualized in this piece.

In another work, entitled p-Orbital, the berimbau (example 3, the last instrument on the score) is part of an ensemble with nine other instruments (flute, two bass clarinets, trumpet, electric guitar, piano, violin, cello, bass). The piece explores a wide array of elements varying from textural material to spectral harmonies, from raw sounds coming out of bottles of water and sand paper to driving rhythmic elements. To some extent, the techniques used for the berimbau in this piece follow the traditions of the instrument. However, here the berimbau is used to generate noise, varying from harmonic and to inharmonic sounds, which functions as a link between the various kinds of materials used in the piece. Noise elements resulting from frictional and percussive articulation, harmonic entities, and rhythmic flow, the berimbau underlies the grammar while controlling the musical syntax throughout the piece. Consciously avoiding the traps of simplistic stereotyping while being reinforced by the orchestral instruments, the sounds of the berimbau are completely re-contextualized in this piece.

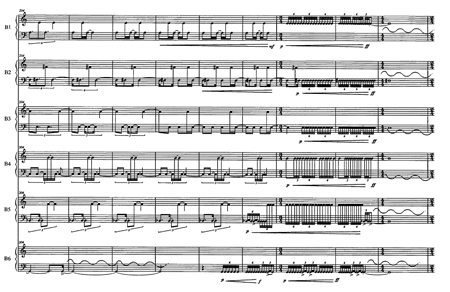

21In Repercussio (example 4), written for six berimbaus, each instrument has different dimensions both in length and diameter, resulting in six different fundamentals. To expand the pitch possibilities even further and to be able to work with more complex harmonies, the placement of the gourd along the wire was carefully planned according to specific frequency ratios, e.g. 4 :3, 4 :1, 3 :2, etc., which allowed each instrument to basically have two fundamentals. In the example below, densities and textures, along with polyrhythm and sound spatialization, i.e., techniques and procedures commonly used in contemporary music, all were used to create and expand a musical text that hopes to transcend cultural and aesthetical boundaries. Another important aspect to consider is the pedagogical value of this kind of work. The musicians must not only learn how to play the new instrument, but also be acquainted with historical and sociological developments. There have been many attempts to incorporate ethnic instruments into chamber ensembles and orchestras, but in many cases the results have been simplistic and stereotyped in nature. Among the reasons for this oversimplification of the material has to do with the difficulties of learning and mastering a traditional instrument and making it more than an ornamental part of an ensemble with modern instruments. It is also a result of perceiving such mixtures as merely exoticism, which is a complex discussion that goes beyond the scope of this article. Therefore, no orchestra yet exists in which violins and flutes share the same space with the African-Brazilian berimbau, the Chinese sheng, the Japanese sho, the Iranian tanbur, and many other instruments from cultures worldwide.

Example 4. Alexandre Lunsqui’s Repercussio for six berimbaus (2005).

Final Considerations: Future

22With its capacity for generating individual intellectual and emotional responses while accessing aspects of group identification, music can echo ideas and easily travel beyond geographic boundaries. Conversely, music can be manipulated by a powerful industry insensitive to its cultural, social and artistic values. The immateriality17 of music is inevitably affected and transformed by the materiality of the context. While on the one hand music has the potential to enrich, enlighten, and instigate cultural and social consciousness, on the other it can be transformed into a mere object (product) to serve all kinds of non-musical purposes. It is not by accident that the mass media find the most marketable music one that barely provokes an intellectual response18. Less materialistic behavior will not threaten social, economical, scientific or artistic development. Quite the contrary, it is a question of balancing development and political and social behaviors accordingly to respect, understanding and multiplicity.

23Today, every aspect of contemporary life gravitates around an economic system that has been gradually adopted – or imposed, depending on the analysis – across the planet. The virtues and flaws of this system are intrinsically related to the process of globalization, which in its turn is dangerously based on the accumulation of power, hegemonic attitude, and distorted materialistic needs stimulated by the lure of consumerism. In music, the notion of tradition and avant-garde, East and West, North and South must co-exist under the umbrella of artistic creation and integrity. In life, tradition and avant-garde, East and West, North and South must co-exist under the umbrella of humanity. If we are not prepared to respect other cultures around the world, independent of their political orientation and economical status, then the process of globalization needs to be revised, for it must not result in cultural and environmental corrosion.

Bibliographie

Beyer Gregory, “O Berimbau. A Project of Ethnomusicological Research, Musicological Analysis, and Creative Endeavor”, Unpublished Dissertation, 2004.

Castillo Monique, “World citizenship today: Kantian cosmopolitism facing globalization”, http://monique.castillo.online.fr/pdf/alexandrie_2002.pdf (consulted in August 2006).

Croce Benedeto, “Art as Intuition”, in Art and Philosophy, New York, St Martin’s Press, 1964, p. 46-59.

DeWitt John, Early Globalization and the Economic Development of the United States and Brazil, Westport, Praeger Publishers, 2002.

Deleuze Gilles, Guattari, Félix, A thousand plateaus: capitalism and schizophrenia, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

Franklin M.I., Resounding International Relations on Music, Culture, and Politics. New York, Palgrave MacMillan, 2005.

Faria Hamilton, “Arte e Identidade Cultural na Construção de um Mundo Solidário”, Encontro Mundial dos Artistas da Aliança, http://www.polis.org.br/publicacoes_interno.asp ?codigo =104 (August 2006).

Feld Steven, “A Sweet Lullaby for World Music” in Public Culture n° 12, Winter 2000, p. 145-171.

Hobsbaum Eric, Nations and Nationalism since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Pignatari Décio, Cultura Pós-Nacionalista, Rio de Janeiro, Imago Editora, 1998.

Steigerwald David, Culture’s Vanities: The Paradox of Cultural Diversity in a Globalized World, Oxford, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc., 2004.

Notes

1 The writers were: Machado de Assis (1839-1908), João da Cruz e Souza (1861-1898), and Pedro Kilkerry (1885-1917).

2 Décio Pignatari. Cultura Pós-Nacionalista. Rio de Janeiro, Imago Editora, 1998, p. 39. (translated from Portuguese by Alexandre Lunsqui).

3 Steven Feld, “A Sweet Lullaby for World Music”, in Public Culture n° 12, Winter 2000, p. 154.

4 “The International Convention on the protection of the diversity of cultural contents and artistic expressions will officially establish that cultural productions and property require a special status different from the status of other products and services that are subject to gradual liberalization and more extensive trade”. (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, http://www.ohchr.org/english/law/diversity.htm, consulted in August 2006).

5 Steven Feld, op. cit., p. 146.

6 “[…world music] swept through the public sphere first and foremost signifying a global industry, one focused on marketing danceable ethnicity and exotic alterity on the world pleasure and commodity map”. (Ibid., p. 151)

7 Ibid., p. 156.

8 Ibid., p. 161.

9 Hamilton Faria. Arte e Identidade Cultural na Construção de um Mundo Solidário, Encontro Mundial dos Artistas da Aliança, p. 10, http://www.polis.org.br/publicacoes_interno.asp ?codigo =104 (consulted in August 2006).

10 The immateriality of these artistic expressions : the intangible or metaphysical qualities intrinsic to a musical work, as opposed to materialistic values.

11 UNESCO : http://portal.unesco.org/culture/en (consulted in August 2006).

12 Steven Feld. op. cit., p. 166.

13 Gregory Beyer. “O Berimbau. A Project of Ethnomusicological Research, Musicological Analysis, and Creative Endeavor”. Unpublished Dissertation, 2004, p. 1.

14 Ibid., p. 182.

15 Capoeira is a fighting dance created by the slaves in colonial Brazil around 400 years ago. It was a way to resist their oppressors and celebrate their own traditions. Capoeira continues to be widely practiced in Brazil and has also spread to other parts of the world.

16 Ibid., p. 188.

17 Gilles Deleuze speaks of the strong deterritorializing force of music. Accordingly to him, this “explains the collective fascination exerted by music, and even the potentiality of a ‘fascist’ danger we mentioned a little earlier : music (drums, trumpets) draws people and armies into a race that can go all the way to the abyss (much more so than banners and flags, which are paintings, means of classification, and rallying)” (Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari. A thousand plateaus : capitalism and schizophrenia. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1987, p. 302).

18 In Culture’s Vanities, David Steigerwald states : “There is no cultural ruling class left, strictly speaking, though the economic and political ruling class is alive and well. Where political and economic elites have discovered that they can rule without insisting on class-based cultural standards – indeed that their interests are best served by the absence of such standards - the critique of snobbery becomes mere evasion. The only cultural standard of our day is whatever sells, and to the small degree that art has any political purpose, its power to effect change, or even to rattle the status quo, is enormously diminished. It is equally clear that culture as a way of life has lost its democratic character”. (David Steigerwald, Culture’s Vanities : The Paradox of Cultural Diversity in a Globalized World, Oxford, Rowman and Littlefield Publishers Inc., 2004, p. 237).

Citation

Auteur

Quelques mots à propos de : Alexandre Lunsqui